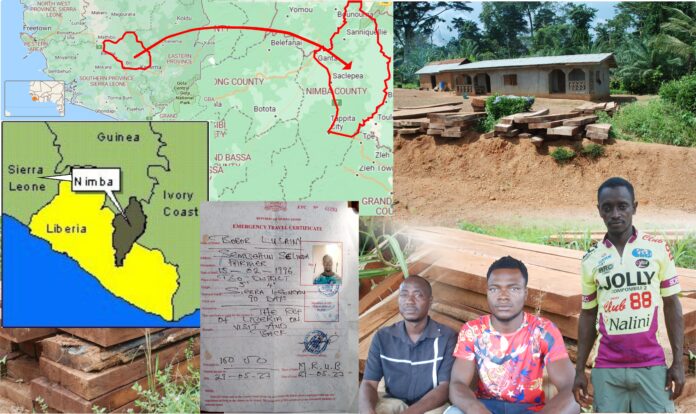

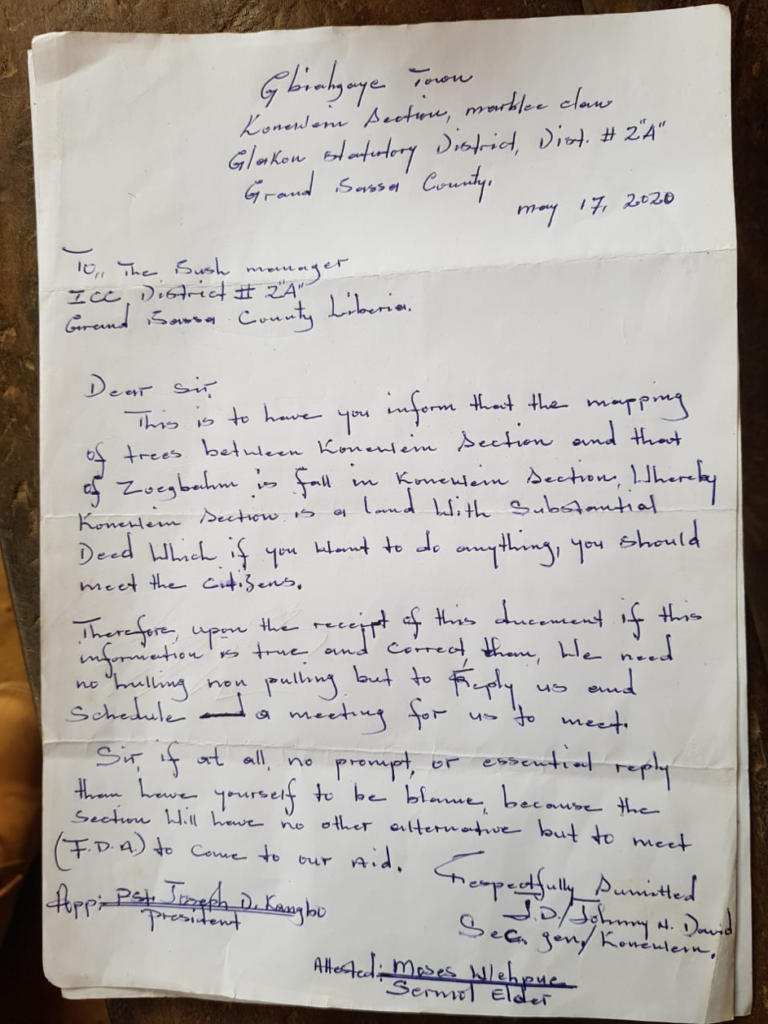

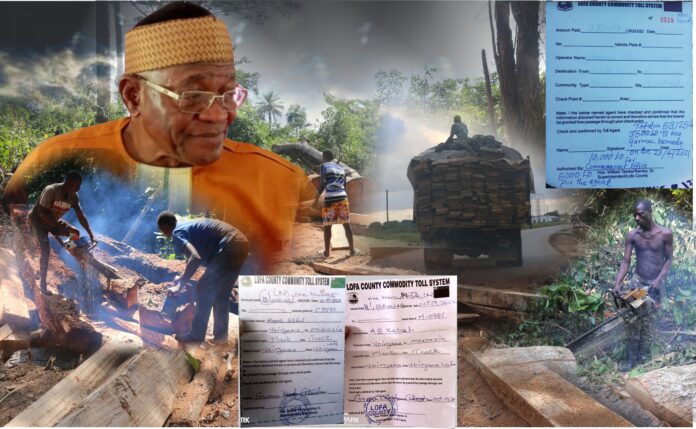

Top: Kpokolo seized at the FDA checkpoint in Klay, Bomi County. A report by U.S.-based Forest Trends launched today says kpokolo threatens Liberia’s rainforests and undermines the country’s climate change efforts. The DayLight/James Harding Giahyue

By James Harding Giahyue

- “Kpokolo,” a new form of illegal logging threatens Liberia’s rainforests, provides little benefit for the country and undermines its climate efforts.

- Kpokolo harms small-scale loggers, who are the sole suppliers of wood to the domestic markets. Big companies are taking advantage of the illegal trade

- The report calls on President-elect Joseph Boakai to take clear steps in banning kpokolo and punish violators of the ban

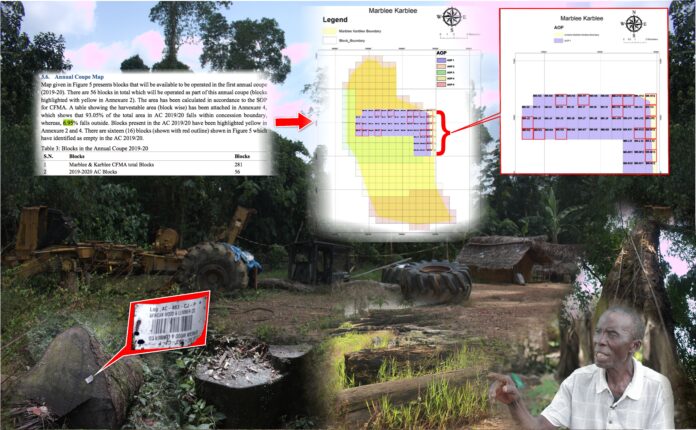

MONROVIA – Thick, four-cornered and expensive timber produced illegally across the country and smuggled in containers, are a threat to Liberia’s forests, and undermine its efforts to combat climate change, a report launched today by the US-based Forest Trends, has found.

The report—“‘Kpokolo’: A New Threat to Liberia Forest”—found that block wood or kpokolo, as it is commonly called, has no legal basis and harms small-scale loggers, rural communities and the country. It calls for a ban imposed on the illegal logging earlier this year to be made clear and official.

“The illegal exploitation takes advantages of weaknesses in enforcement, corrupting officials and compromising processes…,” Arthur Blundell one of the report’s two coauthors, told The DayLight.

“The newly elected president should take immediate steps to halt this illegal exploitation by confirming an official ban of kpokolo, including devoting resources for the enforcement of the prohibition,” Blundell added.

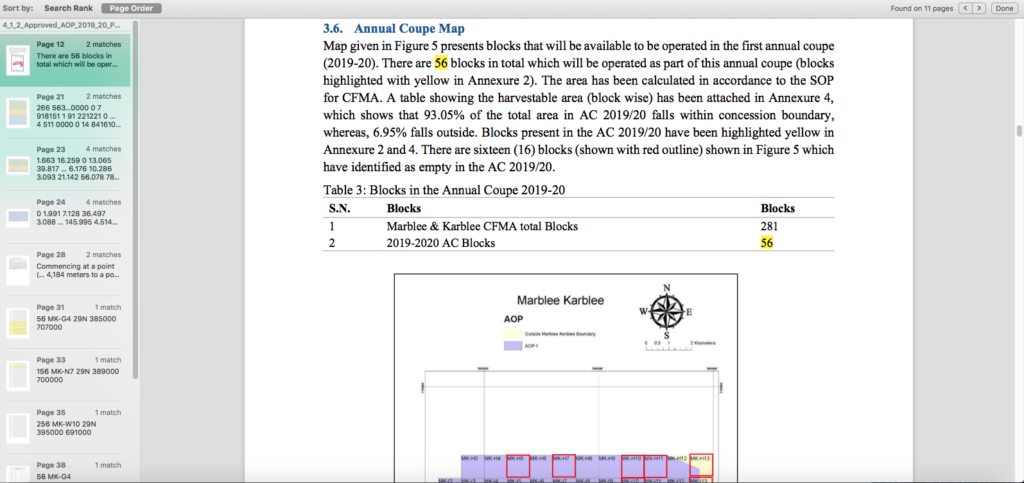

Based on interviews and media reports—including from The DayLight—the report suggested that kpokolo might have begun in the 2010s. It operates within the plank subindustry. However, the size of planks, which are two inches thick, differs sharply from kpokolo, which can be up to 12 inches thick, the report said.

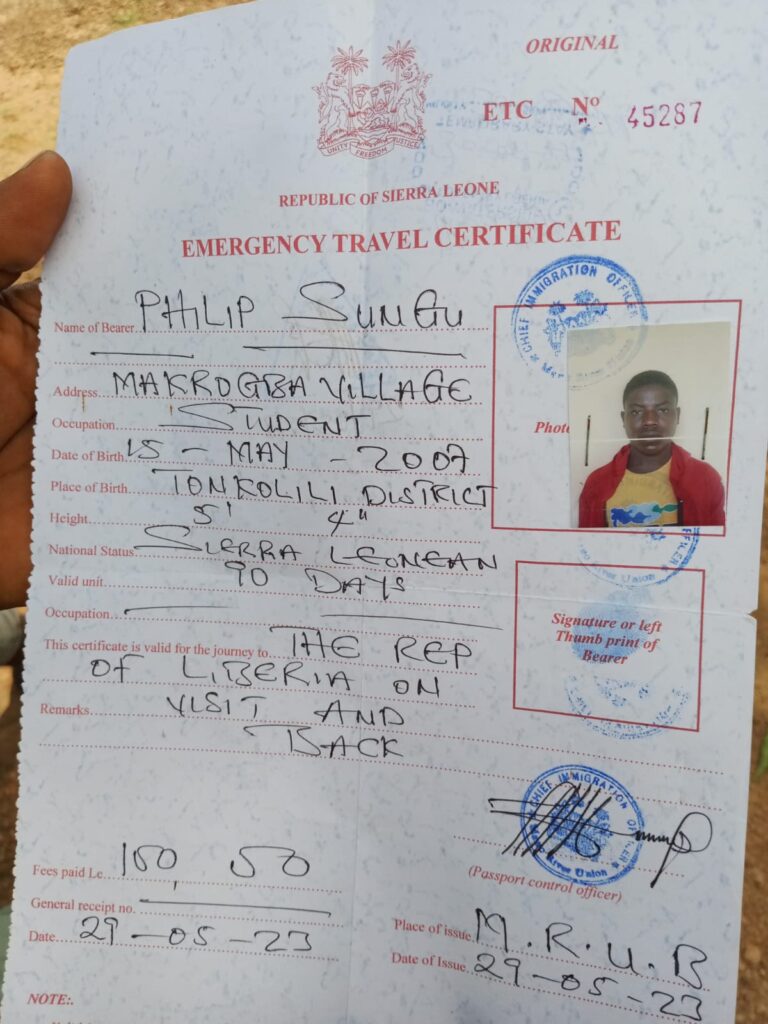

Between October and December last year, researchers interviewed 267 community dwellers, chainsaw operators and wood dealers in eight counties for the kpokolo report. It is an update to a 2016 report on the wood market in Liberia.

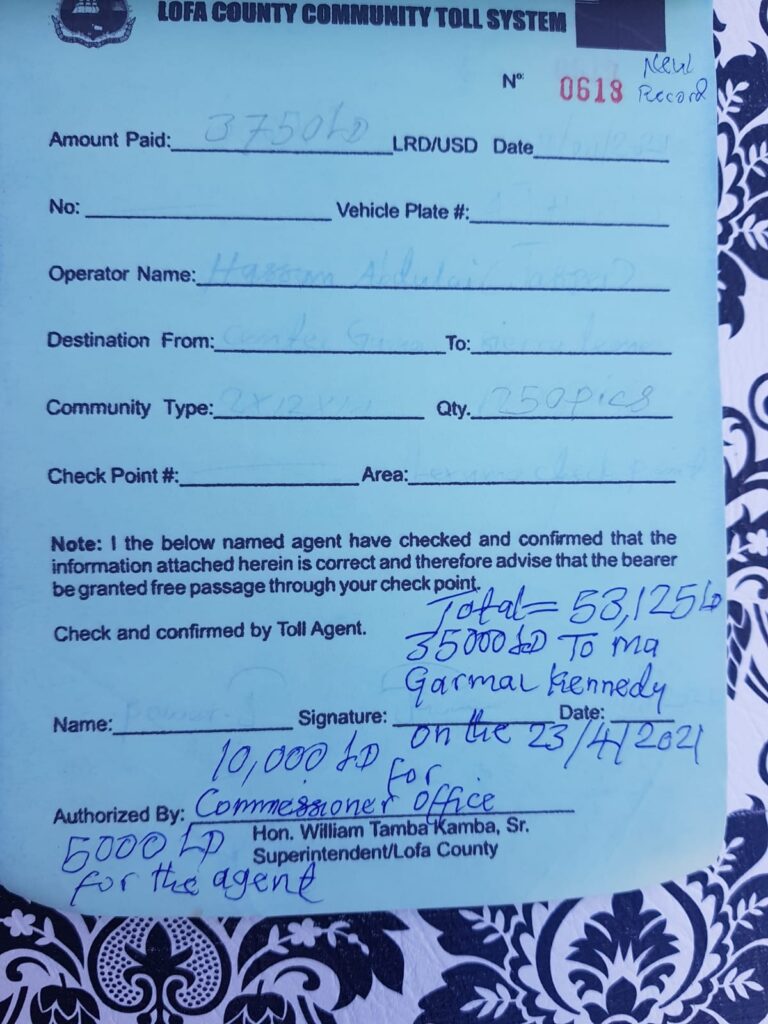

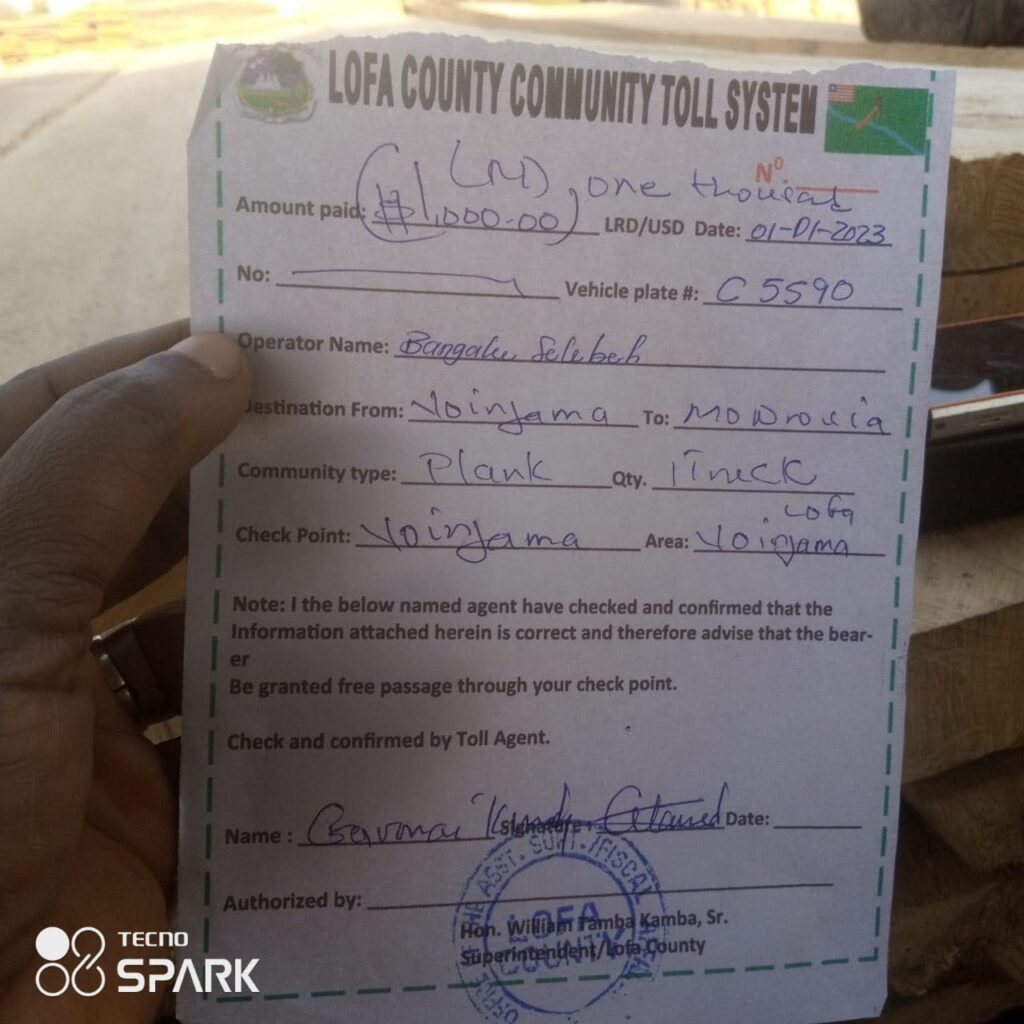

The Forestry Development Authority (FDA) did not immediately respond to questions for comments on the report. The agency had, at least officially, sanctioned the illegal operation, collecting fees from operators to transport the wood.

‘Economic sabotage’

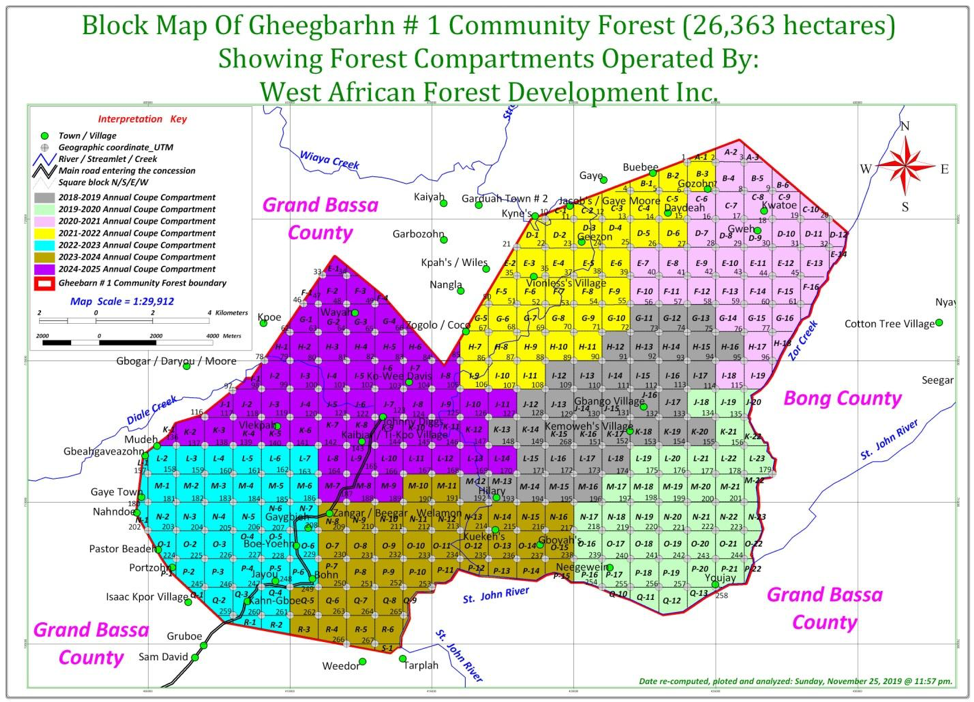

The report did not find sufficient evidence on the scale of kpokolo but found enough cases where the new form of illegal logging posed a threat to the country. It said kpokolo undermined Liberia’s climate change efforts, and the protection of the country’s forest, West Africa’s largest remaining rainforest. Liberia has pledged to the United Nations to reduce deforestation by 50 percent by 2030 among other commitments.

The coauthors of the report called for the entire industry to rally against kpokolo.

“Without such a whole-sector approach, Liberia risks allowing illegal logging to undermine not just [sustainable forest management] but governance in rural areas more broadly as kpokolo has a corrupting influence on local authorities and community leaders,” Blundell said.

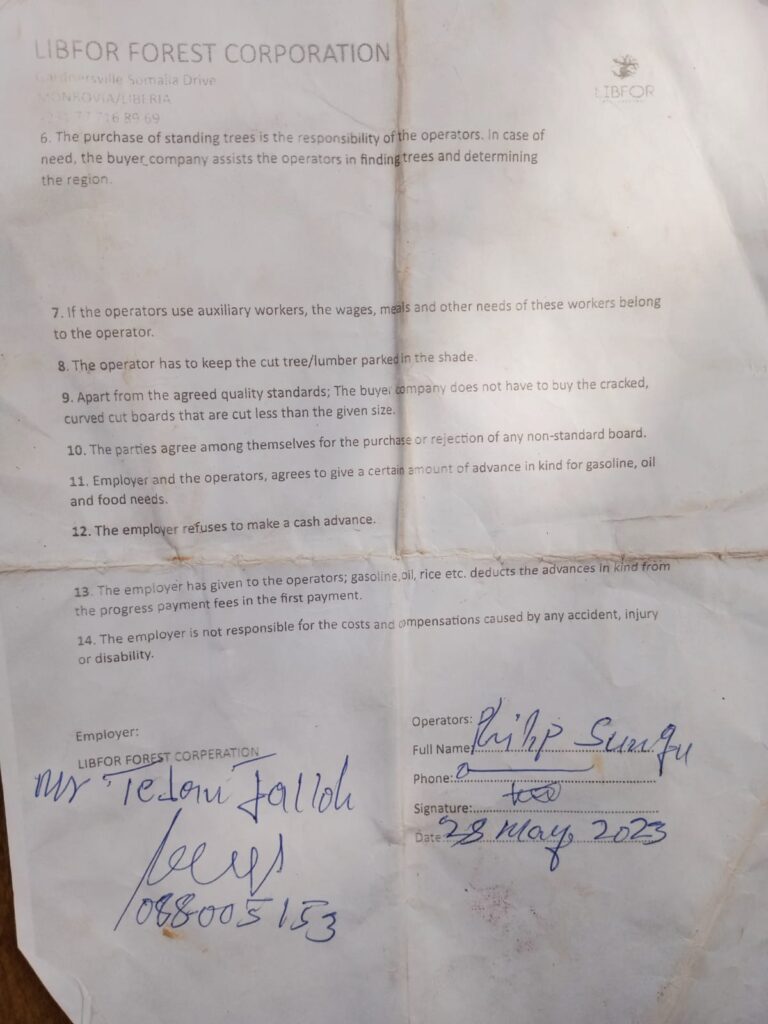

The report gathered evidence that large companies were exploiting the kpokolo situation to “squeeze out artisanal operators who supply the local wood markets.”

Operators, known in the industry as chainsaw millers, perhaps need to promote a recently adopted regulation to limit kpokolo, the report suggested.

Though chainsaw milling has been largely unregulated since its emergence in the 2000s, the subindustry has been allowed to supply much-needed wood to the domestic markets. One FDA report dubs it a “necessary evil.”

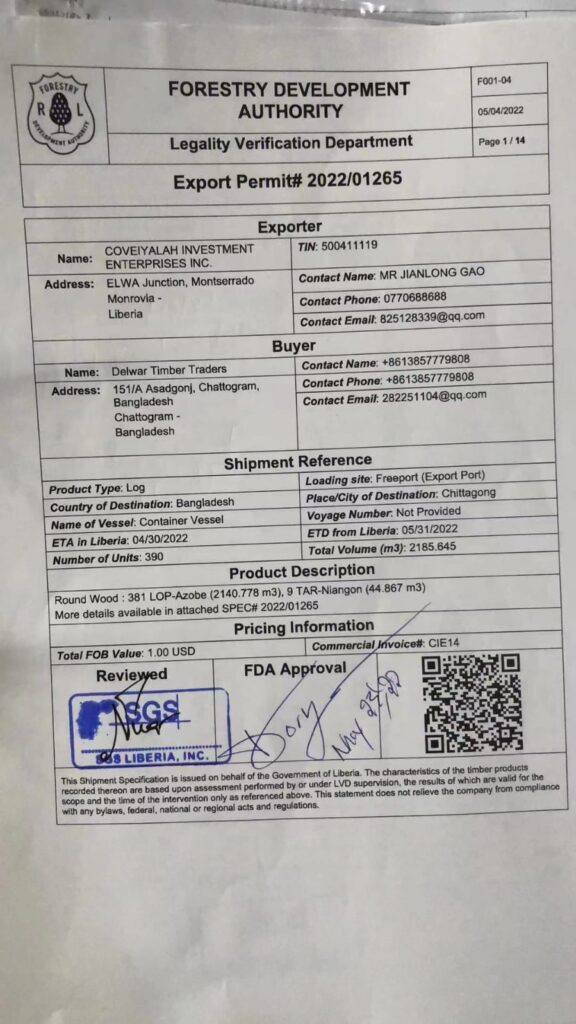

People researchers interviewed said companies were exporting the wood to Ukraine before its war with Russia. Researchers learned that kpokolo timber were being exported for railroad ties, which matched the dimensions of the illegal wood.

The report quoted people stating companies were smuggling kpokolo through containers, one of them Akewa Group of Companies, a Nigerian-owned firm that has violated nearly every forestry law. There is a mention of Askon Liberia General Trading Inc., which was debarred from forestry over its illegal operations, with its Turkish owners arrested in May. Akewa did not respond to questions over its alleged involvement in kpokolo.

In February, three months before the ban, the FDA had announced that it had banned kpokolo. In June Liberia also discussed the ban at an annual forestry meeting with the European Union.

Those steps were not enough and that kpokolo could still be ongoing as operators could claim they are unaware of the ban, according to the report. Forest Trends recommends that President-elect Joseph Boakai makes a detailed announcement of the ban, capturing legal instruments supporting the ban, the definition of kpokolo, and penalties for violating it.

“If the ban is not carefully detailed and widely disseminated, it is unlikely to be effective in the face of powerful business forces involved,” said Kristin Canby, a senior director of Forest Trends’ Forest Trade and Finance Initiative that led the report.

“The ban must be followed by a clear demonstration of enforcement,” Canby said in a press release.

David Young, the other coauthor of the report said violators of the ban should be punished in line with forestry laws and regulations, “including economic sabotage for complicit officials.

“As part of a renewed commitment by the FDA under the new administration, enforcement should include punishing kpokolo operators and buyers of their wood, as well as the corrupt officials that allowed the illegal exploitation,” Young told The DayLight.