Top: A Sierra Leonean truck awaits locals in Vahun, Lofa County to smuggle planks into the neighboring country. The DayLight/James Harding Giahyue

By James Harding Giahyue

- A self-proclaimed aide of the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) and a customs officer collect fees on planks exported to Sierra Leone through Vahun, Lofa County

- But the export of such woods is strictly prohibited under forestry legal frameworks

- The smuggling of planks is an open secret and has been going on in that region for years

- Vahun’s bad road networks and its closeness to Sierra Leone fuel the illicit trade

- The FDA said it is investigating the matter

VAHUN, Lofa County – Planks produced in Liberia are not allowed to be exported. They are made solely to support construction works within the country since round logs are meant entirely for foreign markets.

But that rule does not apply in Vahun, Lofa County’s district on Liberia’s northwest border with Sierra Leone. Locals here smuggle planks in broad daylight, thanks to agents of the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) and Liberia Revenue Authority (LRA).

Instead of blocking the trafficking of wood, the agents do the exact opposite. Abraham Konneh, a villager who claims to be an aide, gets unspecified amounts on consignments of planks crossing the border. Richard Gbargondah, the LRA chief collector in that region, collects L$20 on each wood.

“The FDA people are aware that we sell the wood in Sierra Leone. LRA and the police, too,” said Daoda Kromah, a chainsaw miller in the region. The FDA and the LRA get toll.” Daoda Kromah is not his real. His and the names of other chainsaw millers in this story have been changed to protect them from any reprisals.

The DayLight obtained a number of receipts of the illegal transactions. That was also corroborated by chiefs, elders, and plank makers, known in the forestry sector as pit-sawyers or chainsaw millers. The term “chainsaw millers” come from the millers’ use of chainsaws or power saws. “Pit-sawyers” connotes a centuries-old method of producing planks with a handheld saw by placing a tree trunk over a pit.

It appeared the isolated nature of Vahun, one of the most forested places in Liberia, plays a part in the plank scam. The district is cut off from other parts of Lofa due to its bad road networks. People here conduct all of their businesses across the border, including the purchases of gasoline and spare parts for chainsaws. In fact, they even use Leone, the Sierra Leonean currency.

‘Just a token’

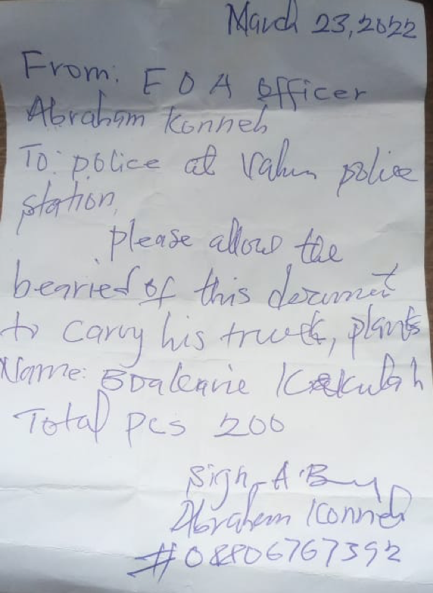

“Please allow the [bearer] of this document to carry his truck of planks,” Konneh said to the Vahun police depot in a note, seen by The DayLight. It was in reference to 200 planks that were to be trafficked on March 23 earlier this year.

Konneh said Ben Miller, an FDA ranger assigned at the Proposed Wonegizi Nature Reserve, appointed him as an aide, a claim supported by other villagers. He said he collected up to 200,000 Leones (L$1,700) on each transport of planks to Sierra Leone.

“The sawyers themselves declare [their production] and give what they have,” Konneh said in an interview. “Sometimes they don’t pay. It is just a token.” We caught up with Miller 139 miles away in Konia but he declined an interview.

Gbargondah’s LRA scam is more organized than Konneh’s FDA profiteering. It all started with a meeting on tax collection Gbargondah organized some time ago. He had convinced locals that paying taxes would record Vahun’s contribution to the Liberian government’s revenue.

“I did not want to be counted among the unproductive custom officers,” said Gbargondah, who controls the tax region from Barziwen, Zorzor District to the Sierra Leonean border in Vahun.

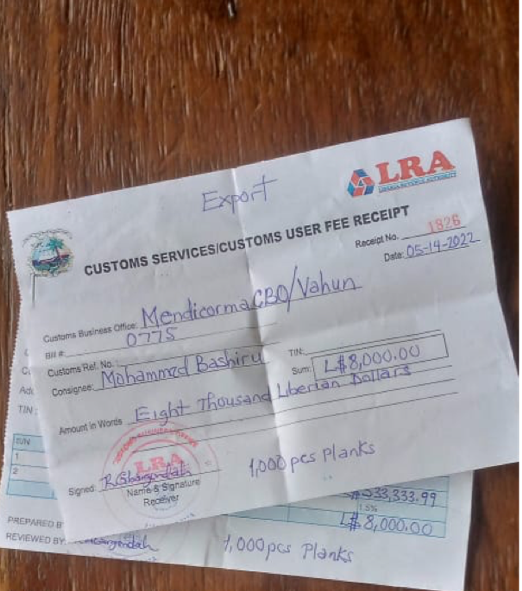

People started to comply with the tax code, including Gbargondah’s illegal plank scheme. He charges L$20 on each plank and only allows records from 100 pieces and above. Unlike the FDA agent, he provides official LRA receipts to make the payments look genuine, deceiving the townspeople that the money they pay goes into the government’s revenue.

Gbargondah claimed that he started to collect the duties on planks just four months ago. However, receipts of some of the illegal transactions show earlier dates. He collected L$8,000 on 1,000 planks valued at L$533,333.99 on May 14, 2022, for example, according to one of the documents.

Also, the procedure for payment in Gbargondah’s scheme is a red flag. Invoices for the exportation of timber do not come from the LRA. They are generated within the chain of custody, a system that tracks the wood from their sources to the buyers, and has become to be a game-changer in Liberia’s quest to tackle illegal logging. It is a major component of Liberia’s trade agreement with the European Union, known as the Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA).

‘We are not happy’

Abraham Konnehs handwritten note to the police in Vahun

A receipt issued by Richard Gbargondah an LRA customs officer in Lofa

Vahun’s chainsaw millers said they were aware planks are not to be sold on foreign soil but had no option. Predominantly farmers and gardeners, incomes from smuggled planks help them clean their farms and take care of household needs, according to them. They said they sell construction and furniture woods between L$600 and L$1,400 in Leones. Ishmael Kamokai, a chainsaw miller in a town called Folima told The DayLight his main customer was a woman in the Sierra Leonean city of Kenema he only named Lucia.

Piles of newly milled planks lined up the route to the border in the Guma Mande Clan. Rotting planks, blackened from years of rain and sunbath, could be seen nearly everywhere on the 30-mile road.

A heavy truck with a Sierra Leonean license plate was parked in Folima. Kromah, Kamokai and townspeople interviewed said the vehicle crossed the border nearly every week, transporting up to 250 planks per trip. It is the most infamous of all the smuggling vehicles. Ibrahim Sannoh, its driver, evaded an interview.

“We are not happy as Liberians to take the resources of the country to carry in Sierra Leone but no other way,” said Kamokai.

“Vahun has lots of resources, including diamonds, gold and other things. Because of the lacking of road connectivity completely, this is why most of our resources can go to the neighboring country,” adds Mohammed Kamara, the central clan chief for Guma Mande. “You cannot expect people who live here with resources and they are not well connected to their own country.”

The road from Vahun to Kolahun is one of the worst in the country. Untrimmed bushes make it difficult to see the ground. Erosion caused by yearly rainfalls, rocks and steep hills feature almost permanently. At one point, it takes a deep left turn at the head of a cliff so deep that even the green and yellow coloring of a cocoa garden on its side could not cover the lurking danger.

Kromah narrated how he and other chainsaw millers attempted to transport some 800 planks to Voinjama in a truck in 2017 but lost all the woods. He said they had to pay for the repair of the vehicle and needed a full year to recover from the loss.

“If you go on the road, you will see some of the woods,” he said with a dry smile. “We lost more than L$1 million.”

The LRA did not reply to queries emailed them nearly two weeks ago up to writing time.

The FDA said it did not have a local office in Vahun, and that Miller had denied authorizing Konneh to collect fees in the name of the agency. Konneh also denied he collects tolls, despite admitting to doing so in our interview.

“We do not take this at face value and are investigating along with the authorities,” said Yanquoi Dolo, the head of the FDA legal team in an emailed statement.

Edward Blamo contributed to this report.

This story was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).