Top: The headquarters of the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) in Whein Town, Paynesville. The DayLight/James Harding Giahyue

By James Harding Giahyue

WHEIN TOWN, Paynesville – The Managing Director of the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) Mike Doryen and top managers of the agency award export permits to logging companies outside of the legal channel for the exportation of timber, documents obtained by The DayLight have revealed.

By the National Forestry Reform Law, all export permits and certificates of origin must be “accurately enrolled” in a log-tracking or chain-of-custody system known as LiberTrace. Under the law, granting access to forest resources that breaks any provision of the law constitutes economic sabotage.

But Doryen and other top managers awarded Rosemart Inc., a Liberian-owned company, and Porgal Enterprise Inc., an Ivorian-owned firm, a certificate of origin and export permits that are not registered in the official log-tracking system.

Rosemart used the illegal permit and sold 520 teak logs, expensive, durable woods used for construction, shipbuilding and the making of AK-47 rifles. Rosemart was selling the logs for US$26,588, according to the illegal document.

Porgal’s illegal papers were tracked down in Cote d’Ivoire.

The other managers who signed the illegal permits are Joseph Tally, Doryen’s deputy for operations; Edward Kamara, the manager for forest products marketing and revenue forecast; and Jerry Yonmah, the former technical manager for the agency’s commercial department.

FDA’s legality verification department confirmed it did not issue the documents, which, of course, do not match the ones generated by the chain of custody system. Permits issued by the system carry barcodes and other markings absent on the ones awarded to Rosemart and Porgal, and are free of human errors. That standard is a crucial part of Liberia’s Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA) with the European Union (EU) for the trade of legal and sustainable timber.

“I have no idea what [those permits are],” said Gertrude Nyaley, the technical manager for the department. “What I know is that all woods and wood products must be exported [through] the LiberTrace system. Anything shipment of timber or timber products outside the chain-of-custody system is illegal.”

Receipts of the transactions and review of official payment records of both companies show Rosemart and Porgal did not pay the fees for the permits to the Liberia Revenue Authority (LRA), as mandated by law.

The permits undermine the forestry objectives of the Pro-Poor Agenda for Prosperity and Development to increase the sector’s contribution to the Liberian economy. It aims to increase forestry revenue from nine to 12 percent by next year. However, logging contributed US$9.2 million to revenues in the 2020-2021 fiscal year—when the illegal permits were awarded—the LEITI reported. That was only a tenth of the country’s revenue from extractive industries for that period.

Porgal denied any wrongdoing, and Rosemart refused to comment on the matter.

Doryen, Kamara and Yonmah did not respond to our emailed questions posed to them.

Talley claimed he and the other officials acted in line with forestry legal frameworks.

Errors and Inconsistencies

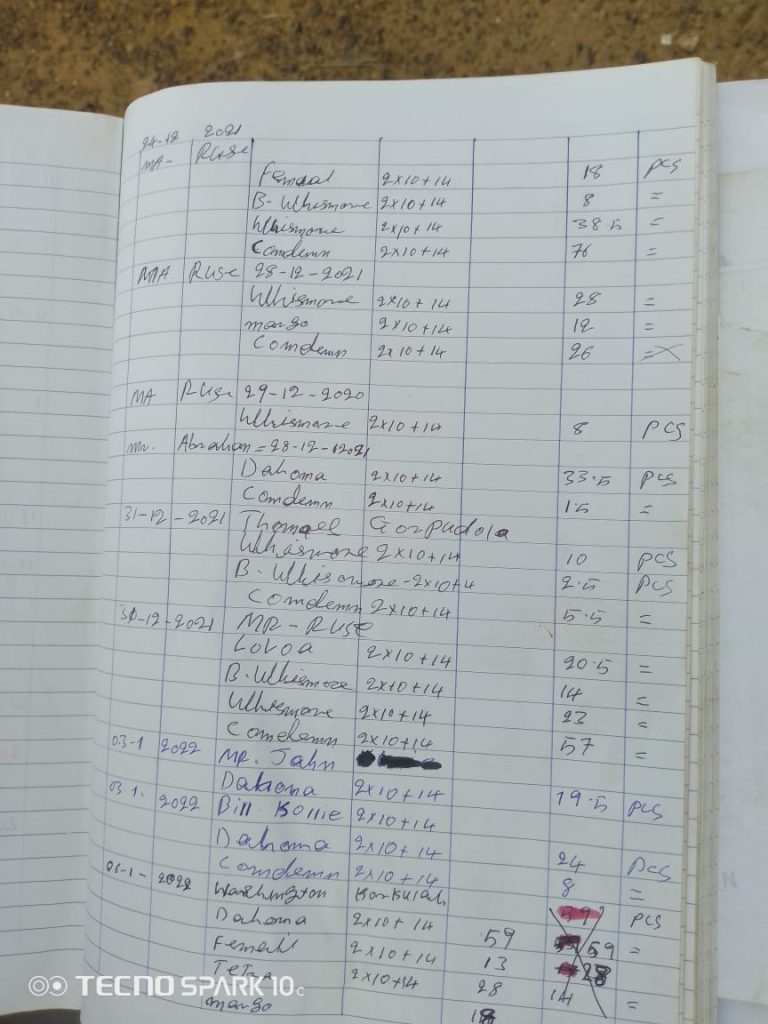

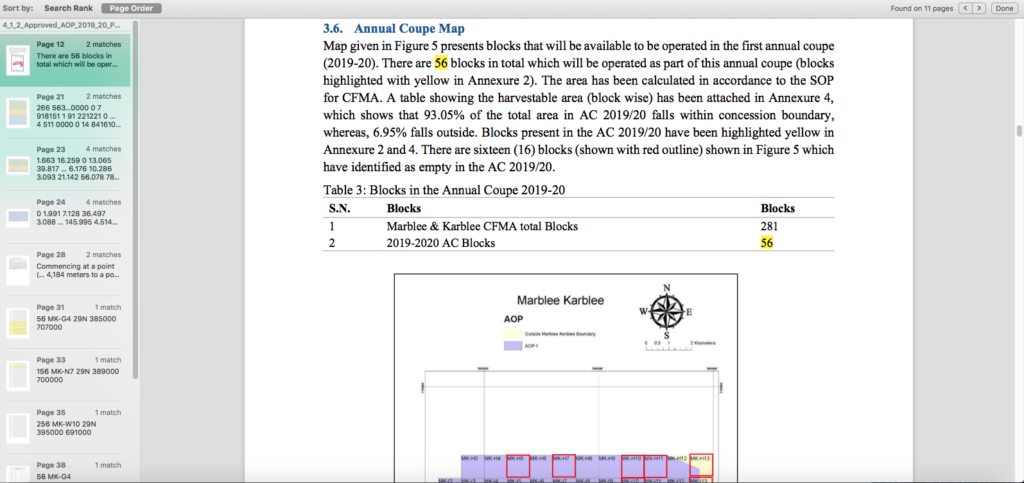

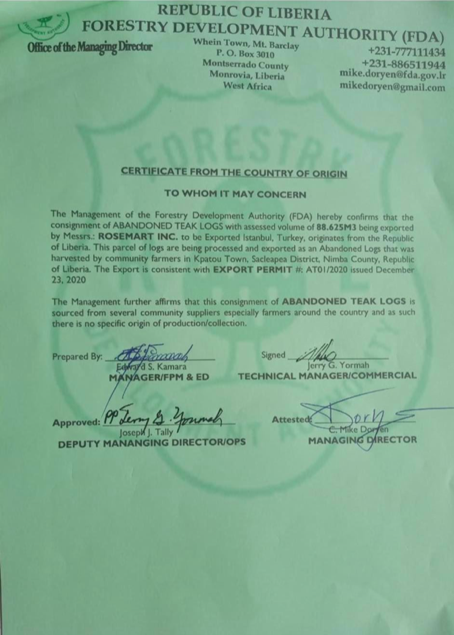

Rosemart’s permits were issued in quick succession. It paid the so-called export fees on December 23, 2020. That same day Doryen acknowledged the payment of US$1,430 for “abandoned” teak logs with a total volume of 88.625 cubic meters from a forest in Kpatuo, Nimba County. The company then received a certificate of origin, which tells a prospective buyer where the logs come from. Then later that day, it was awarded the export permit.

“This export permit is valid upon attestation by the Managing Director/FDA or his designate and is for a single shipment,” Doryen’s letter read.

“You are further requested to work closely with the relevant government agencies, including FDA forest law enforcement, Liberia Revenue Authority/Customs & Excise, [National Port Authority] and [Ministry of Finance and Development Planning] agents who will monitor and supervise the process,” it added.

Rosemart’s illegal export permit

Rosemart’s illegal certificate of origin

Chain-of-custody legality aside, Doryen’s awarding of Rosemart a permit to export the supposed abandoned logs was also unlawful. Unattended logs can be exported only if the FDA publicly declares them abandoned and seeks a court order for an auction. There has been no such petition at the Eighth Judicial Circuit Court in Sanniquillie or anywhere since the Regulation on Abandoned Logs, Timber and Timber Products was created in 2017. Up to press time, local radio stations had no records of notices of abandoned logs and auctions as mandated by the regulation.

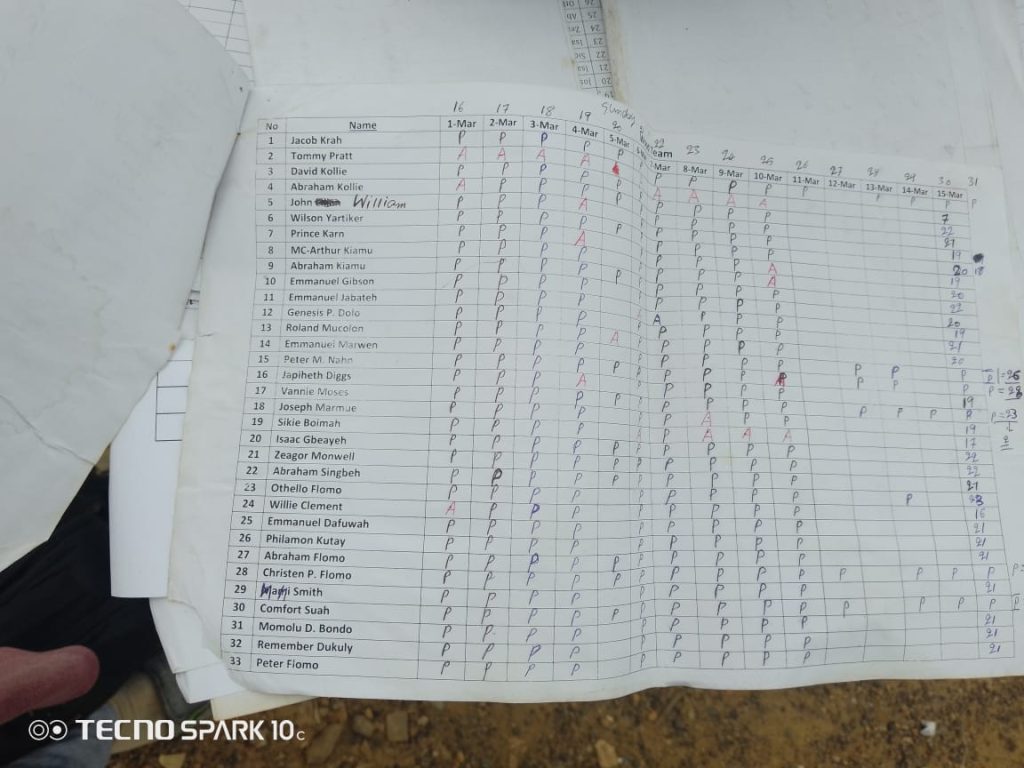

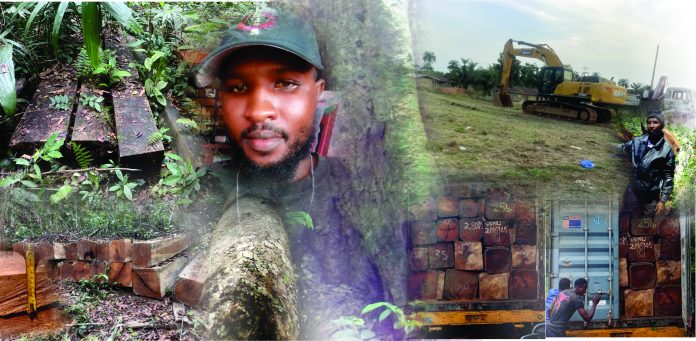

Doryen’s claim in the certificate of origin that the woods were “sourced from several community suppliers, especially farmers around the country and as such there is no specific origin of production/collection” is not factual. Pictures we obtained from a source familiar with the illegal harvesting show some of the teak logs and their stumps in Kpaytuo Plantation deep in the Saclepea region. A stump is the portion of the tree that remains in the ground after harvesting.

There were also a number of inconsistencies in Rosemart’s documents.

Doryen’s letter to the company and the certificate of origin listed Turkey as the destination of the logs but that changed to India on the export permit, despite all documents being written on the same day. Indusina Exim LLP, the Indian firm named on the export permit, did not return queries for comments on the deal.

It appeared the permit, certificate and letter were copied and pasted from old ones, with the authorities retaining previous validity periods in new ones. The actual export permit was issued on December 23, 2020, but reversely valid up to February 21, 2020. Doryen’s letter to Rosemart—meant to reinforce the permit—was backwardly valid from January 30 to March 15, 2019. The validity period of the letter was 45 days and the permit 60.

The documents misspelled Jerry Yonmah’s Surname as “Yormah” yet he signed them. Yonmah alongside other staff was suspended earlier this year over his alleged role in granting some logging companies trees above their annual harvesting limits. He was subsequently replaced as technical manager of the commercial department.

It was unclear where the money Rosemart paid the FDA went. The so-called permit fees went to the FDA’s account at the United Bank for Africa, according to Doryen’s letter. Rosemart paid another US$1,335 for export and another wood-related fee. But its tax history only reflects a US$664.70 payment for forest products, which was made on February 20 last year. It was also blurry whether the company paid land rental and other fees as mandated by law.

Teak woods Rosemart illegally harvested in Nimba

A stump of a tree Rosemart illegally harvested in Nimba

There were indications Rosemart had traded illegally sourced logs more than once. The firm is not named in any of the reports of the Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (LEITI). It was established in 2014, and villagers adjacent to the Kpatuo plantation said it had operated the forest before 2020. The Commissioner of Kpaytuo Township Adolphus Kpangar, said Rosemart has an agreement with locals wherein it pays US$15,000 for a certain quantity of logs, adding they had had three transactions. Rosemart has transacted between US$1 million and US$2.5 million annual sales volume on the Trade Key alone, according to the Saudi Arabia-based e-commerce platform. The company also deals in general merchandise, though.

The FDA did not grant our request for Rosemart’s logging contract, a violation of our right of access to such public information, guaranteed under the National Forest Reform Law and the Freedom of Information Act.

Rose Yancy Adikwu, Rosemart’s co-owner and CEO, turned down an interview with The DayLight. Adikwu had promised to grant us the interview but backed off as soon as we shared copies of the permits. Further efforts to persuade her proved futile.

Porgal’s Permit in Cote d’Ivoire

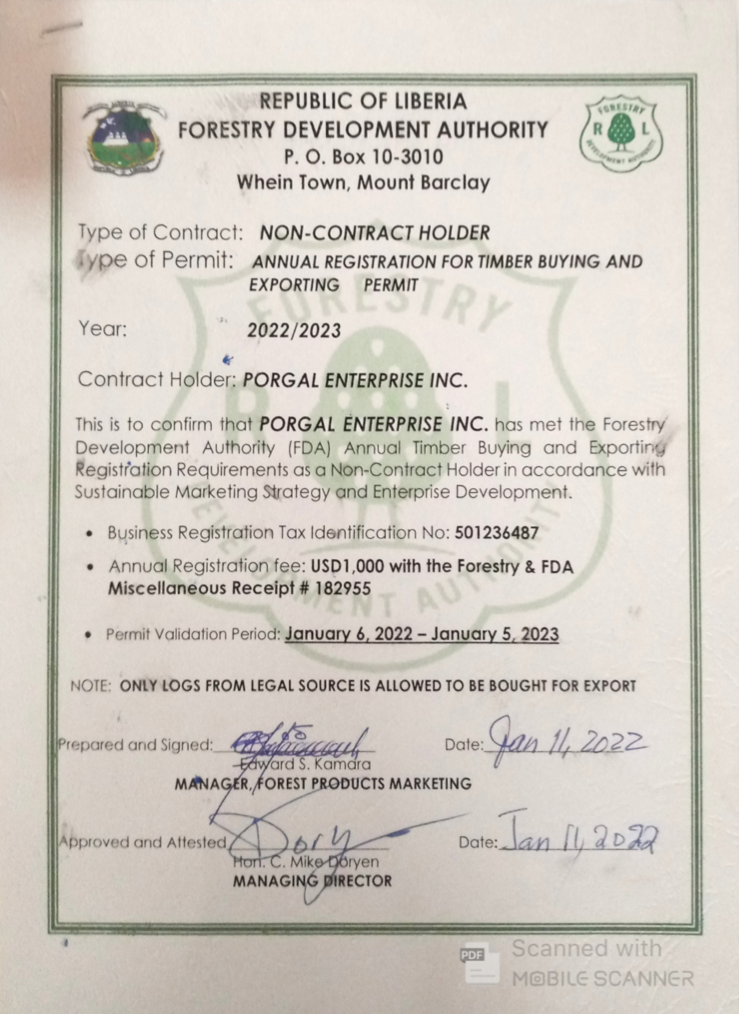

On January 11 this year, Doryen and Kamara awarded Porgal Enterprise Inc. a one-year permit to purchase and export timber and timber products. This time around, only Doryen and Kamara signed the permit.

“This is to confirm that Porgal enterprise Inc. has met the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) annual timber buying and exporting registration requirements as a non-contract holder…,” the permit read.

The illegal permit was awarded to an Ivorian wood company, Porgal Enterprise Inc.

Porgal paid US$1,000 for the permit but, like Rosemart, the disbursement was not made to the LRA. Rather, it was paid to the FDA’s account at the Liberia Bank for Development and Investment (LBDI), a receipt of the payment shows. The company’s taxpayment history also corroborates this. It only reflects disbursements for business registration, resident permit and other fees, not the export permit.

Earlier this year, Ivoirian authorities reached out to the FDA to inquire about Porgal’s permit and other documents relating to timber presumed destined for Burkina Faso or Mali, according to a communication between forestry personnel of the two countries, seen by The DayLight.

Amadou Barry, the Ivorian national who owns Porgal denied any wrongdoing, blaming apparent imposters. “I don’t know anything about fraud,” Barry said in a WhatsApp chat. He said he had been quizzed by FDA rangers on this issue.

“We did not buy wood from Liberia, so we are not related to this case,” added Hamado Ouedraogo, a representative of Wend-Noura International, Porgal’s Ivorian partner. Both companies had signed a contract to export timber from Liberia barely a week before the FDA awarded Porgal the illegal permit, the contract seen by The DayLight shows.

Tally, FDA’s deputy managing director for operations, falsely claimed that the permits did not have to be awarded through the chain of custody system.

“Within the next few weeks, all necessary information to have the public adequately knowledgeable on the issuance of [the] export permit will be published,” Tally said in an emailed reply to The DayLight. “We will inform the general public on a regular or periodic basis… for better understanding as relating to your concerns.”

Gerald Koinyeneh contributed to this report.

The story was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).