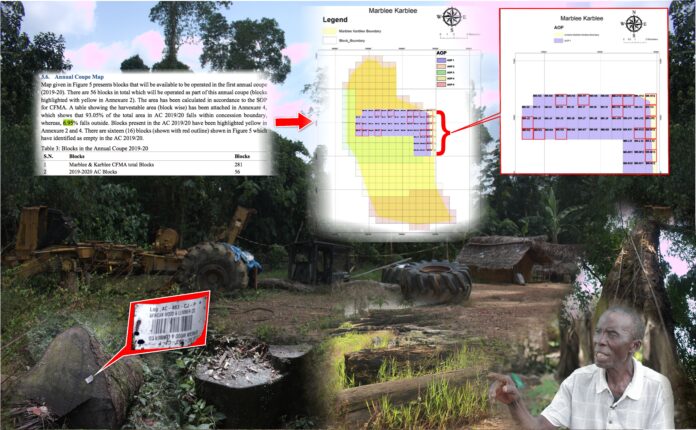

Top: Logs, abandoned by Alma Wood in Vanjah Village, Grand Cape Mount County. The DayLight/James Harding Giahyue

By James Harding Giahyue and Varney Kamara

Editor’s Note: This is the second of a series on the aftermaths of timber sale contracts (TSCs) across the country, which were canceled in March 2021 following years of illegitimacy.

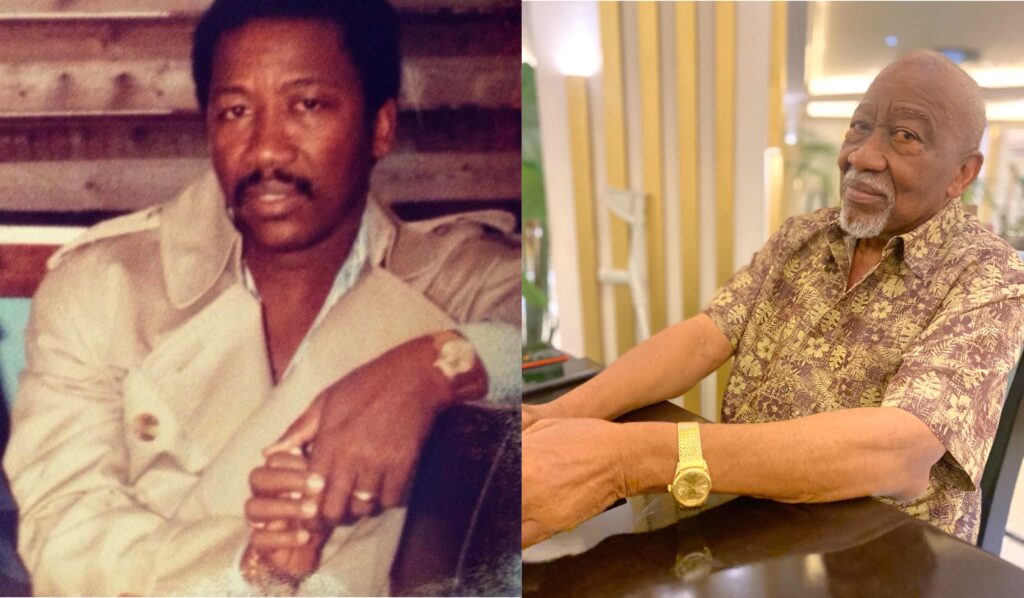

VANJAH VILLAGE – The company of a Lebanese businessman fleeing the law abandoned an unspecified number of logs in Grand Cape Mount County, with the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) doing little to address the problem, an investigation by The DayLight has found.

In 2018, Alma Wood Corporation (Liberia), co-owned by El Zein Hassan, abandoned the woods in a small-scale logging concession in the Gola Konneh and Porkpa Districts of Grand Cape Mount County. Hassan fled the country the following year over a debt lawsuit with Afriland Bank, leaving the logs unattended in different locations in the area.

“There are many logs left abandoned and damaged in the bush,” Aaron Quaye, a community leader, told The DayLight. There are over 5,000 cubic meters [of logs] in the forests.”

This reporter saw scores of the woods scattered across the forest, the company’s log yard in a town called Mafalla, another town named Gohn and Vanjah Village. Some locals were burning the logs to make charcoal in Mafalla. Quaye said there were more logs in forests but The DayLight could not reach them due to the difficult road network in that region.

The DayLight’s calculation of the company’s official production and export records between 2018 and 2020 shows that it did not ship 519.267 cubic meters of logs it harvested in that area. That number could be more, given that the records only show the company’s 2018 production in the concession affecting Vanjah Village and Benduma town, where Quaye lives, not the forest around Bong Village, where Alma Wood also operated.

Woods are abandoned if they are “unattended” between 15 and 180 working days depending on their location, according to Regulation 116-17 on Abandoned Log, Timber and Timber Products. It was created in 2017 and repealed certain sections of Regulation 108-07 that narrowed the definition for “abandoned logs” as logs outside a contract area without tracking barcodes.

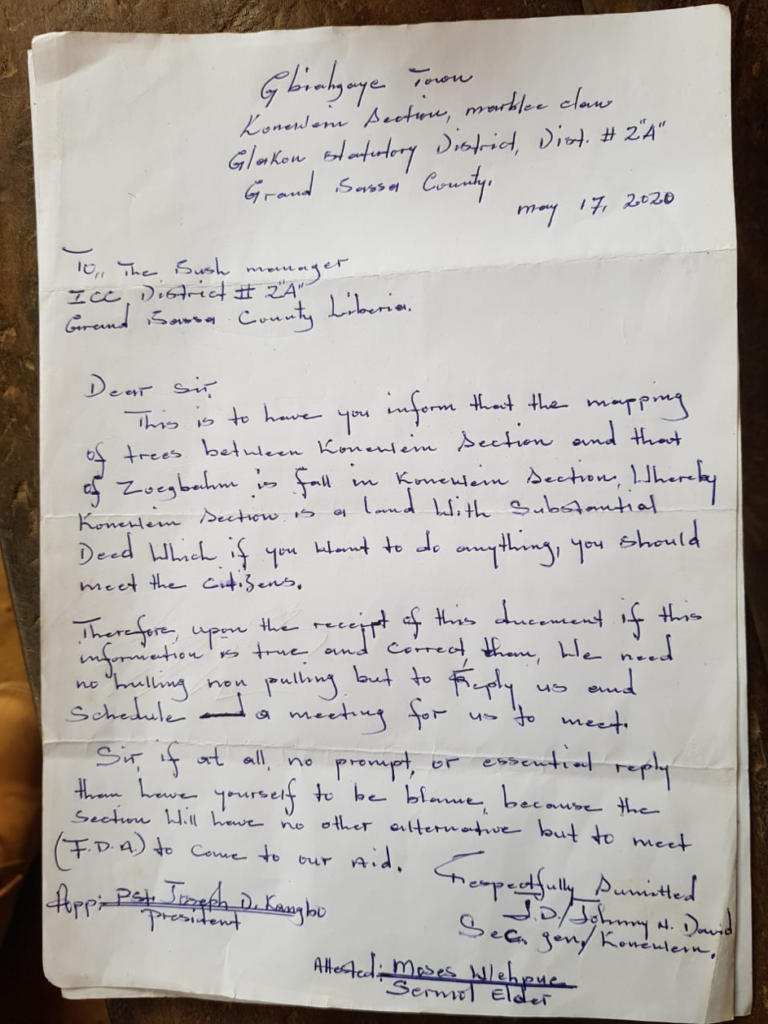

The regulation requires the FDA to notify the public over a long period once it learns of the situation. Ruth Varney, the agency’s representative in the western region, confirmed to DayLight the community had told her about the abandoned logs.

In April earlier this year, the FDA gave all logging companies a one-month period to declare logs they have harvested as it takes inventory of probably abandoned logs countrywide. That deadline has expired a month ago and the agency said it would begin auctioning the woods this month.

“Those who did not remove their logs as per the stipulated time, the lawyer will now go to the court to seek judicial action to have the logs confiscated the auctioned,” said FDA’s Managing Director Mike Doryen in a rare interview with The DayLight. “That is a problem that we must solve.”

It was unclear whether the FDA has exhausted a mandatory process in the regulation in order to auction the controversial logs, taking 114 working days or just under six months. Within this time, it needs to investigate, possibly remove the woods to a safe location and make several public notices through the media and its website. It is only when no one claims the logs after that process that the FDA can obtain a court warrant for the auction. Doryen did not show any evidence that these things have been done.

Besides, Alma Wood’s own legal nightmare makes it even harder for a normal auctioning. Earlier this year, the FDA disapproved a deal for the logs to be sold to East End, a company owned by former Minister of Justice Cllr. Benedict Sannoh, over Alma Wood’s lawsuit. The agency learned that the logs had been used as collateral for Sky Insurance Company to pay the bail for Hassan’s release by the Commercial Court in Monrovia.

Hassan had taken a US643,000 loan from Afriland Bank missed several payment deadlines, according to several people familiar with the case (all parties to the case denied The DayLight access to court filings and an interview). Hassan would escape the country thereafter. Efforts by The DayLight to contact him or representatives of the company were not successful.

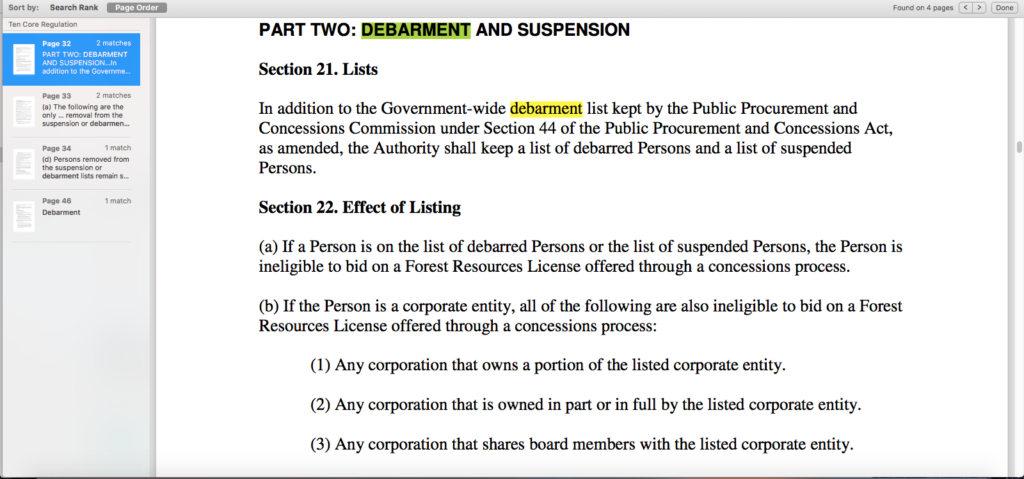

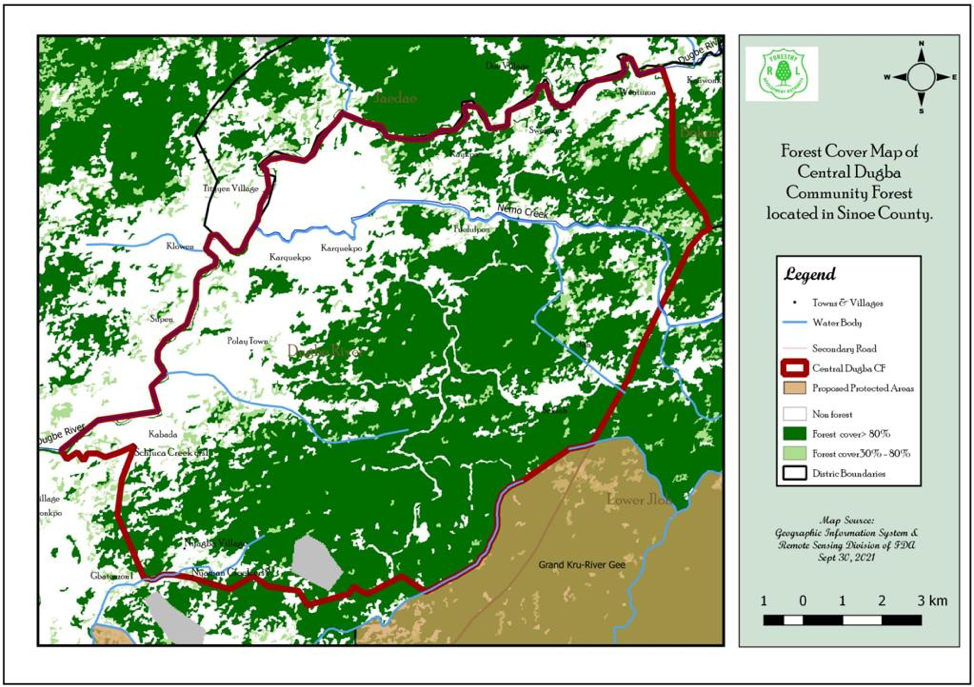

It is not just Hassan’s dealing with the court that is unlawful. Alma Wood’s operations in Porkpa and Gola Konneh are also illegal. Five-thousand-hectare logging concessions, known across the forestry sector as timber sale contracts (TSCs), are meant for only firms with at least 51 percent Liberian shareholdings. The company’s two operations in Cape Mount were some of five illegal deals the FDA signed or sanctioned that we and the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists (CoFEJ) exposed as part of an investigation on TSC across the country. The one in Quaye’s community is called TSC A11 and the other one is TSC A16. Hassan and Radwan Darwiche, a Senegalese man, equally share the company’s 500 stocks, according to its legal documents. It had been subcontracted to the two TSCs in 2016 by Bassa Logging Company, a Liberian firm, and Sun Yeun, a 98 percent Chinese-owned firm, which also breaks the National Forestry Reform Law.

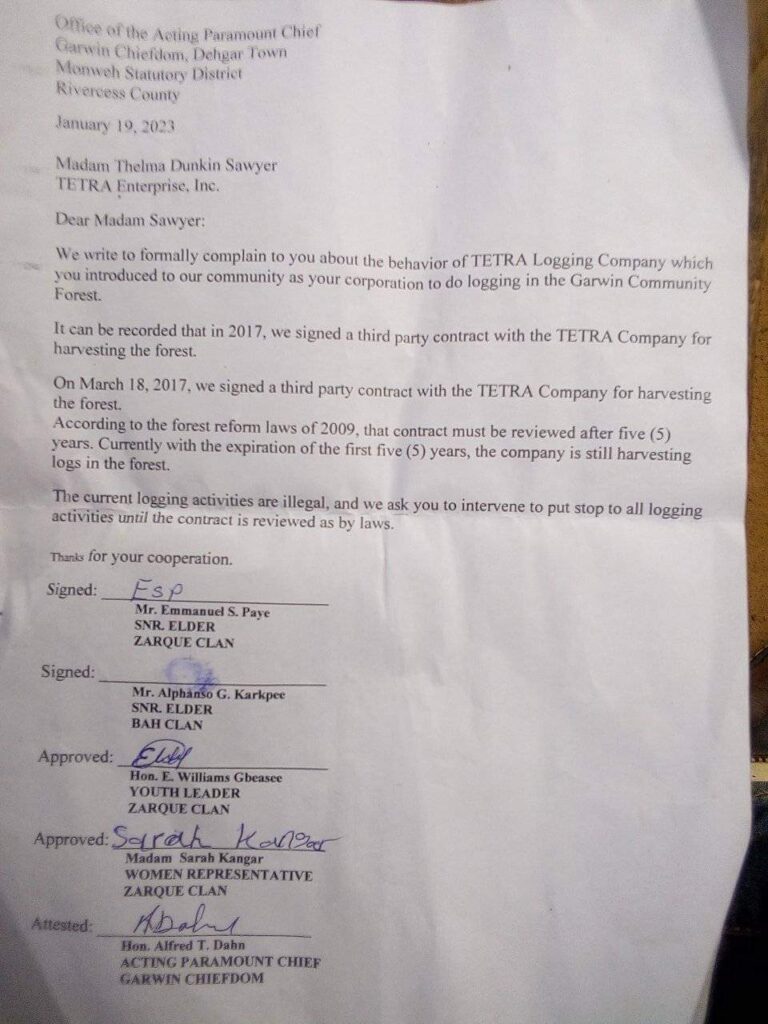

The two TSCs and nine others in Cape Mount, Grand Bassa, Gbarpolu and Bong County overstayed their legal timeframe of at least five years. All lasted for more than a decade combining to establish some of the most chaotic forest licenses of the postwar era.

Josephus Bank, the CEO and co-owner (one percent shareholder) of Sun Yeun claimed that the company had changed shareholders in an interview with us but did not present any evidence. The company has not changed shareholders since its formation in 2008, the documents we obtained from the Liberian Business Registry show. He blamed the FDA for the abandonment of the logs.

Quaye said Clarence Massaquoi, the CEO and co-owner of Bassa Logging, visited the forest last month with an “investor.” Massaquoi did not respond to specific queries on the matter in a WhatsApp chat.

“FDA contributed to those logs being there today. When Alma Wood’s contract expired, I wrote the FDA informing it about logs being [in the forest]. FDA delayed and I wanted to sell at the time,” Banks said in that interview relative to the logs in TSC A16. The FDA refuted that claim.

Massaquoi faces a heavy penalty to redeem the logs amid Hassan’s escape, under the regulation on abandoned logs. He is required to first pay an administrative fee associated with, including the probable transport, storage, security and public notification associated with the woods. Penalties include a payment two times the volume of the logs in question by the legal fees for their stumps. Stumpage fees are calculated based on percentages of the international prices of categories of logs. The regulation was formulated to minimize the waste of forest resources and compel legal compliance in the harvesting and shipment of logs.

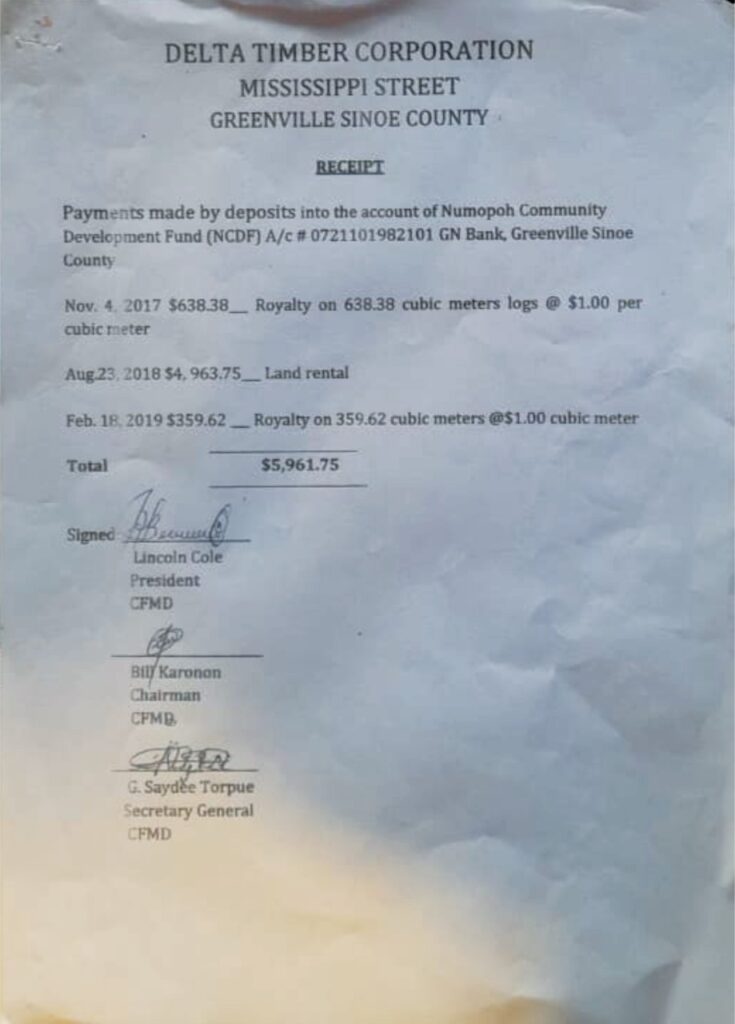

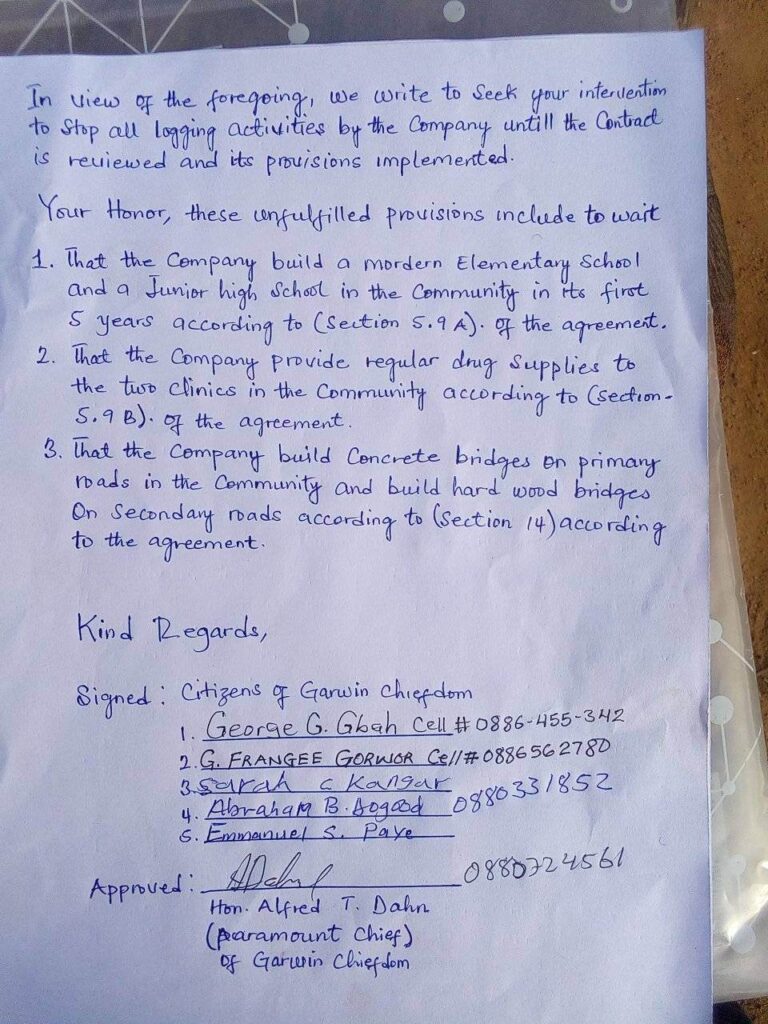

Quaye, who savored an opportunity to join his community’s forest management leadership in 2016, just before Alma Wood signed an agreement with them, said they were the biggest losers in everything. FDA had canceled all TSCs in March last year but did not see to it that communities get their benefits, leaving Alma Wood indebted to him and other villagers. Bassa Logging/Alma Wood owes affected communities US$56,550 in land-related fees, according to official documents. It did not pay villagers a cent for the trees it felled, fees for scholarships and a handpump, Quaye said.

“We regret all these things that are happening to our community,” Quaye said. “We are regretting because it takes so many years for trees to get mature in the forest. Our forest is depleted without any benefit that communities can point to.”

The FDA told an annual meeting of forestry players in March earlier this year that it would work with the union of community leaderships to address overdue payments and other benefits. He restated that in our interview with him.

“We didn’t do that (addressing benefits and other issues),” Doryen said, “but we will do it now.”

This story was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists (CoFEJ) of Liberia and The DayLight.