Top: An elevated view of Huiren Mining Company Camp in Jackson Village, Bong County / The Daylight/ Charles Gbayor

By Matenneh Kieta and Charles Gbayor

JACKSON VILLAGE, Bong County – For years, Melvin Teah drew water from a creek near his home. Teah and other villagers used the water to drink, cook and wash.

Then everything changed in 2020 when some Chinese miners arrived in Jackson Village, one of Bong County’s most famous mining towns.

The miners started digging for gold and created a waste plant close to the creek, poisoning the water. Now, villagers need to walk 10 minutes to the nearest presumably safe creek for water. There is only a single public handpump.

“[Jackson Village] is very large, and we have about 300 persons living here. The handpumps that are here are not even correct three,” Teah said. “We also take water from Gbarnga to drink.”

The situation in Jackson Village could have been better had Huiren Mining Inc. lived up to a memorandum of understanding (MoU) supervised by Bong County lawmaker Marvin Cole.

Jackson Village and the other towns in the clan—Gbarmue, Matthew Village, Kpaah and Banama—have a huge potential for gold, according to the Ministry of Mines and Energy.

The region has been a hub for mainly artisanal mining activities over the years. It was infamous for tragic mining accidents, which helped convince locals to lease their land to the company.

Huiren acquired a class B or medium-scale license for gold in January 2021, which runs to January 2026. Before that, it spent six months there prospecting for the mineral between 2020 and 2021, official records show.

It promised to construct several handpumps for Jackson Village and the other affected communities to lease their land, according to villagers. The DayLight could not verify this claim and others made by the villagers, as the MoU is silent on the company’s social responsibilities.

The residents also accused Huiren of failing to fix roads and bridges in affected towns and villages.

The road from Gbarmue—, the largest of the affected towns and villages— to Jackson Village is rough and rocky with many ditches. Commuters must get down from motorbikes to walk 30 minutes to Jackson Village.

“If we don’t clean this road with our hands and do rehabilitation, cars and motorbikes will not come in,” said Othello Topeoh, a resident of Gbarmue.

Huiren also failed to build a school, and a clinic or provide funding for scholarships, according to the villagers.

Washington Bonnah, the Commissioner of the Jorquelleh District Where Jorpolu falls, denies that assertion. Bonnah said Huiren gave Gbarmue at least US$7,000 to build a school in 2020 or 2021. Marcus Kennedy, a community leader in Jackson Village agreed with Bonnah.

But Larry Gbelekabolu, the Town Chief, denies that. His brother Benedict Gbelekabolu, the youth president of Jorpolu Clan, supported him.

“Before the company came to the community, the gold mining that the community was doing for itself the money generated was what we used to build the school in Gbarmue,” said Benedict Belekabolu.

But Bonnah, the Gbelekabolus and other residents agreed on other things. They all accused Cole, the representative of District Number Three covering the Jorpolu Clan, of concealing the MoU and hijacking their agreement with Huiren.

No one, except an elderly man, had a copy of the document, not even Bonnah or Benedict Gbelekabolu who signed it. A recent survey by CSI or Civics and Service International, a nongovernment organization, found that 94 percent of the Jorpolu Clan have not heard of the MoU. The survey also found 95 percent of the people were unaware of it.

“The MoU shouldn’t be in [hiding],” said Otis Bundor, CSI’s country director. “If the MoU is available to the public, it will be easier to get the full level of accountability.”

In an interview with The DayLight at the Capitol Building in Monrovia, Cole said he had misplaced the document and would look for it.

Cole helped draft the MoU, canceling a previous MoU because of “lots of weaknesses,” and that it was a “disservice” he had not participated in drafting it.

“They needed to specify when they do the [semi-industrial] mining what would come to the community,” Cole said. “Those were the issues I raised, and I think it was based on my level of intelligence and understanding. I was on the [House’s] Committee on Mines and Energy at the time.”

The result of Cole’s arrangement does not justify the lawmaker’s actions. Turns out, the current MoU is weaker than the previous one and is ambiguous like its predecessor.

In the initial document, the community was entitled to US$2,500 quarterly, which amounted to US$10,000 annually.

Interestingly, locals are entitled to US$9,600 yearly in the Cole MoU. That is US$400 less than the annual financial benefits in the discarded document.

That aside, the unavailability of the MoU has wrapped the community’s relationship with Huiren in secrecy. Townspeople do not know whether the miners have paid them any money or not.

Bonnah, who is one of the signatories to the community account, said he was unaware of any transactions. Bonnah added he had not heard from the two other signatories of the account, including a staff in Cole’s office named Solemane Sesay.

Cole said he was unaware Sesay was a signatory to the account but told reporters Sesay had traveled to the United States.

“We were authorized to open the account. [I don’t know the signatories], except I look on the bank statement to know who are those signatories to the account,” said Cole.

Efforts to contact Sesay were unsuccessful. Emory Saylee, a staffer in Cole’s office promised to share Sesay’s contact but did not. Bonnah and other locals did not have it either.

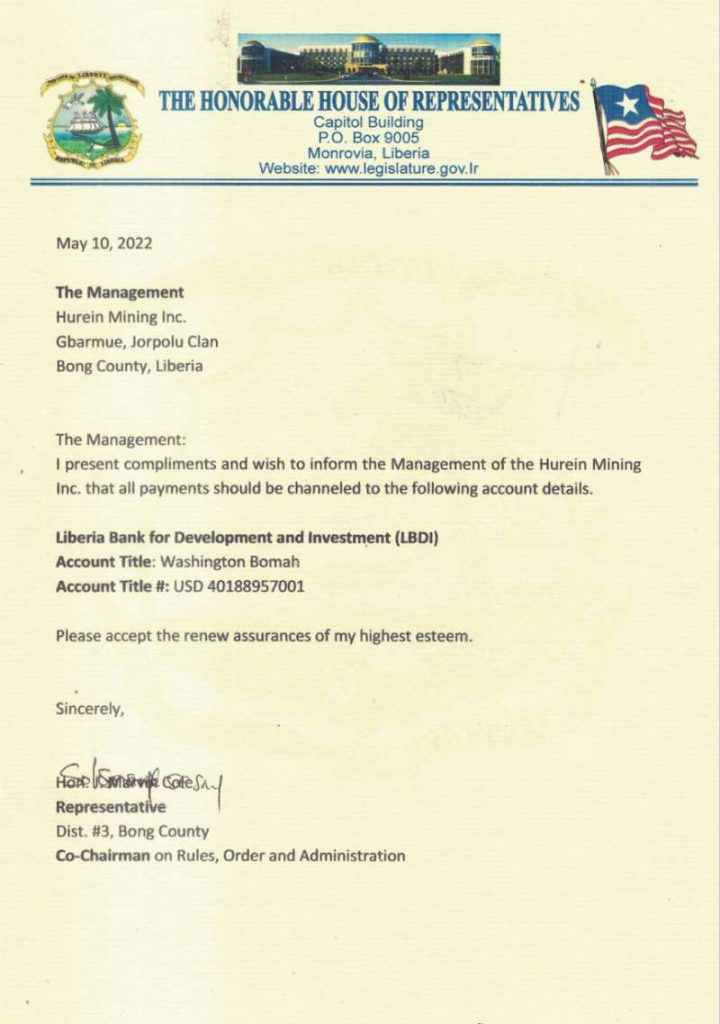

But Cole’s comments are not backed by fact. It was the lawmaker who oversaw the establishment of the bank account, according to a May 10, 2022 letter. Before then, Huiren hand-delivered the money in town hall meetings.

“I present compliments and wish to inform the management of Huiren Mining Inc. that all payments to the following account details,” Cole wrote Huiren. It was an account at the Liberia Bank for Development and Investment (LBDI), entitled “Washington Bomah.”

Bonnah said Cole did not inform him before opening the account. That appears to explain why his name was misspelled as the account title.

Daniel Toe, Huiren’s project manager, said the company has been making periodic payments into the account, and could not be blamed for the stalemate.

“If they say they are not receiving it, they have to be asking their leadership concerning this money,” Toe said in a phone interview.

The DayLight obtained a receipt of a US$4,000 payment from the company made in May last year. Toe said the company would not make future payments until the account issue was resolved.

Toe conceded that the company failed to construct Jorpolu’s roads but blamed the locals for the failure of the other projects.

“They have not come up with any definite project yet for us to get involved,” Toe said.

At a recent community meeting, Fanseh Mulbah, the Deputy Minister for Planning, at the Ministry of Mines, praised the Jorpolu Clan for being peaceful

Mulbah said the Ministry of Mines would investigate the matter.

The United States Embassy provided funding for this story. The DayLight maintained editorial independence over the story’s content.