Top: Villagers work on a farm in Jorpolu Clan in Jorquelleh District, Bong County. The DayLight/Harry Browne

By Matenneh Keita

JORPOLU CLAN, Bong County – In 2019, one year after the Land Rights Act, people in a clan in Jorquelleh District, Bong County, declared their intention to acquire an ancestral land deed.

Jorpolu Clan declared its intention to obtain a deed, known as community self-identification. Then it set up a governance structure to oversee land matters. Now, people of the clan are cutting boundaries with neighboring clans to decide their land size.

But there is a problem. Jorpolu has four boundary disputes with the neighboring Behquelleh and Suakoko Clans. Under the law, communities own land on which their ancestors lived, farmed and hunted. However, they must resolve all their boundary disputes to be granted a title deed.

“We’re talking with [the neighboring clans] and they’re consenting to the discussion,” says Austin Leayne, the secretary for Jorpolu land leadership. “They all can come together for us to discuss the best way forward for everybody to live in peace and harmony.”

Initially, there were 22 boundary issues between the Jorpolu Clan and the adjacent clans. Eighteen have been resolved, with the balance of four issues outstanding. Of those four disputes, Jorpolu has three with Behquelleh and the other with Suakoko.

The first dispute in Behquelleh regards a town called Gbaota. The family of a deceased famous chief there is claiming about 10 acres of land.

The second is related to the first. The land the family claims runs through another town called Gowarmue. However, a memorandum of understanding (MoU) has been drafted for the disputing parties to sign, according to Josephus Blim, program officer with Parley Liberia. The NGO assists Jorpolu and other communities through the legal process of acquiring a customary land deed. Its work is part of a US$3.45 million project funded by the International Land and Forest Tenure Facility headquartered in Sweden.

“Those are just minute places,” Blim said. “I don’t think it would stop the customary process from going on.”

The third land dispute Jorpolu has with Behquelleh is over farmland between a town called Gbarney in Jorpolu and another town in Behquelleh called Kpanyan.

The people from Jorpolu who settled on the land want the land to stay under Jorpolu but a family in Behquelleh wants it to remain there.

Jorpolu’s dispute with Suakoko is the most major. It is a longstanding issue between the two clans over at least 150 acres of land along a creek.

The Woue Creek evenly divides both clans. It takes a deep curve between Gbenjema on the Jorpolu side and Galai on the Suakoko side.

Farmers in Gbenjema who crossed the creek to farm on the land are claiming it but the family of a late elder in Galai counterclaimed it.

“We have made a breakthrough in getting the heirs of the elder to reach a compromise with Jorpolu to resolve the dispute,” Blim said. He added relatives of the late elder attended a recent meeting Parley Liberia organized.

Once Jorpolu resolves all the disputes, the Liberia Land Authority is mandated to survey to confirm the clan’s land and give it a customary deed in line with the law.

Thirty-one communities across the Country lands have been surveyed, according to the Land Authority. About 22 communities have already been granted customary deeds, with Fessibu in Lofa the latest.

People in Jorpolu cannot wait to join the list.

“This land deed is very important to me because during those days women did not have the right to plant anything. Even to plant cocoa on your father’s land… your brothers would say, ‘You don’t have property here,’” says Martha Sheriff, a member of Jorpolu land leadership.

But now, I feel good because of the Land Rights Act that has given me the right to own land and plant cocoa, rubber, and other things on the land for me and my children’s future,” Sheriff added.

“My brothers can’t stop me.”

While a customary deed would solve the Sheriff’s familial problem, it promises enormous benefits for Jorpolu.

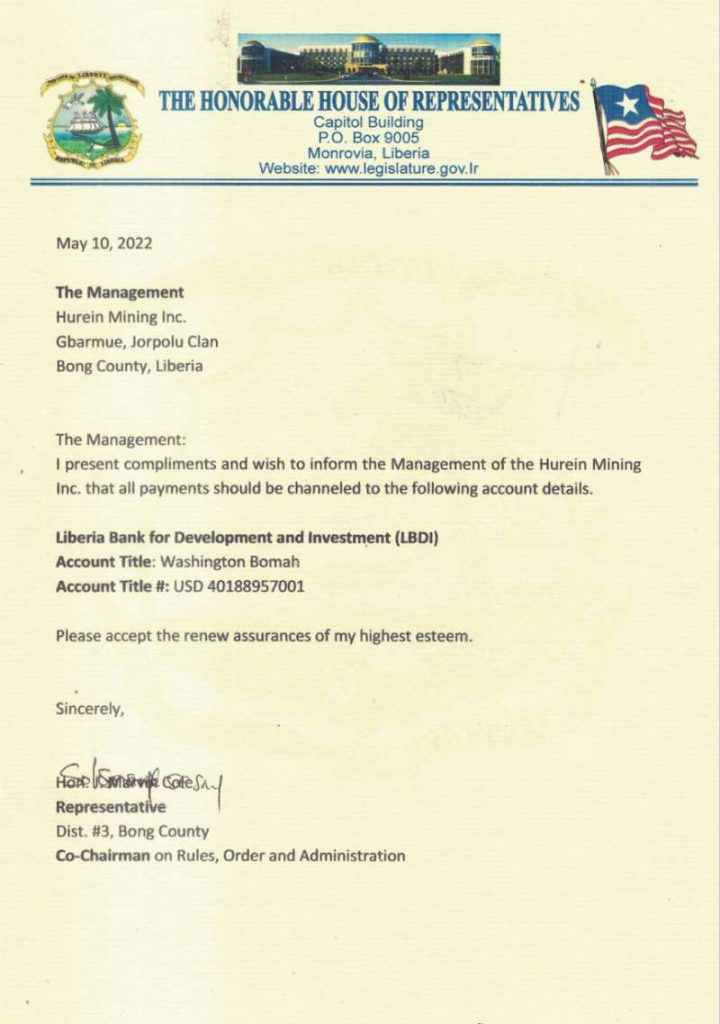

In 2021, Huiren Mining Inc., a mining firm, signed an MoU with few people in the clan and did not live up to it. Neither Jorpolu’s land leadership participated nor was it aware of the document.

Following three years of heightening tension over social benefits, the Ministry of Mines and Energy recently halted Huiren’s operations. A meeting between the company and affected communities is scheduled for next month.

Johnson Kong-bai, the head of the Jorpolu land leadership, rues the marginalization. He believes Jorpolu possession of an ancestral deed will prevent such a thing, though communities are guaranteed customary ownership by the law.

“If I have my deed, I got the full right to go to the company and say, ‘This place you want to operate is my area,’” Kong-bai tells The DayLight. “‘Before you do anything here, you and I will have to sit and discuss what will be the community’ benefit.’”