Top: Smoke billows from the chimneys of GVL’s palm oil mill in Tarjuwon, Sinoe County in June 2024. The DayLight/Derick Snyder

By Esau J. Farr and Derick Snyder

WIEH TOWN, Sinoe County – For nearly 10 years, residents of Wieh Town have endured a pattern of pollution associated with a Golden Veroleum Liberia (GVL) palm oil mill.

The hillside neighborhood in the Tarjuwon District of Sinoe is in the middle of palm wastes produced by the giant-sized mill. At the front of the town stands the mill itself. On the left are three large ponds of the mill-generated effluent or wastewater. On the right and rear are thousands of palm bunches whose nuts the facility turns into crude palm oil.

The smoke from the mill fogs the town, according to locals. The wastewater from the facility pollutes creeks residents once used for drinking, turning a large stream green. The ponds holding wastewater ooze a foul odor like a septic tank. Swarms of flies buzz across the community, attracted by the empty palm husks whose foul odor overwhelms locals.

“No more safe drinking water for us here,” said Levi Jarteh, General Town Chief of Lower Kulu Clan, where Wieh Town is located. “The chemical GVL is using is going into the creeks polluting them and because of that, we no longer use them to drink.”

Jarteh’s and other townspeople’s comments are largely consistent with GVL’s recent environmental audit report, documenting pollution of the mill’s operations. Water samples tested positive for excessive phosphate levels, a chemical compound that can cause human kidney disease. The tests, cited in the report, also show illegal levels of substances and particles.

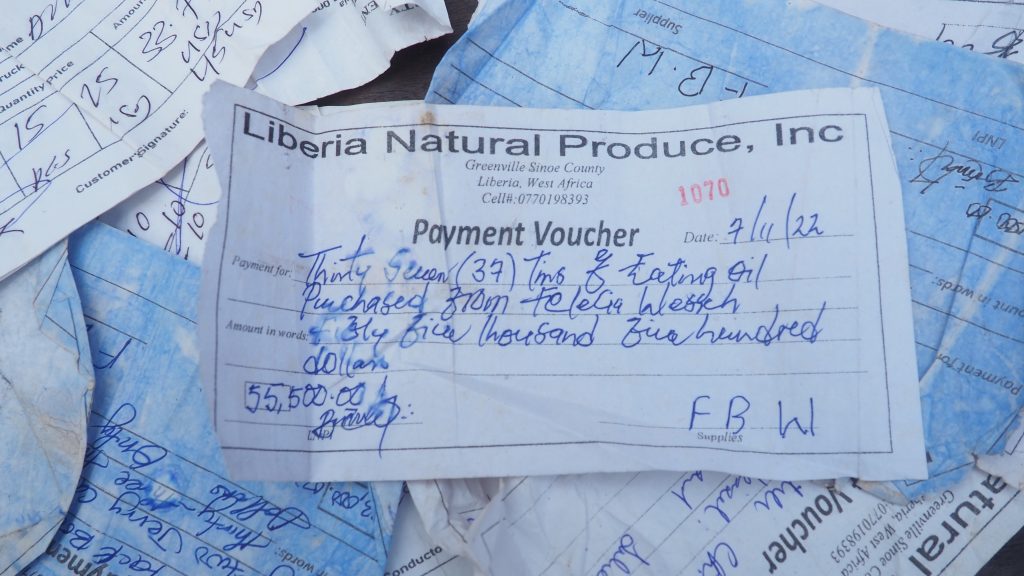

GVL started to build the mill in 2015 and completed it a year later. It can process 80 metric tons of palm nut bunches per hour but produces 40 metric tons per hour. Two huge 2,000-metric-ton tanks and a smaller one are the facility’s most vivid components with a network of chimneys. Between 2020 and 2021 GVL exported 37,534 metric tons of crude palm oil valued at over 31.7 million, according to the Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (LEITI), citing the latest available company data.

But behind the mill’s glamorous profile lies a history of landgrab and violence. In 2013, GVL did not get the Lower Kulu Clan’s consent before developing its plantation and constructing the mill.

So, Lower Kulu filed a complaint with the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), the body that writes the rulebook for the global oil palm industry. GVL is a member of the RSPO through its parent company, the Singapore-listed Golden Agri Resources through the US-based Verdant Fund LP.

The RSPO ruled in favor of the locals, ordering GVL to halt works on the mill until it signed an MoU with Tarjuwon, this time including Wieh Town and other Lower Kulu communities.

GVL’s appeal of the decision was denied. Subsequently, it quit the certification scheme and reentered shortly. It violated that order by continuing to construct the mill, clearing additional forests and building new homes for its workers.

The Liberian government has taken no actions against the company, despite its agreement requiring it to comply with the RSPO’s rules. The former Director General of the National Bureau of Concessions, Edwin Dennis, said he was unaware of RSPO’s decisions against GVL.

Buzzing flies

The land grab, which has left an everlasting scar on Lower Kulu communities, is compounded by the pollution from the mill. GVL uses the husks and wastewater for organic fertilizer. A plant breaks down the palm wastes with water and chemicals and then applies a mixture to the palm trees. However, rainwater mixed with wastewater and most likely runoff from palm husks enters watercourses, the audit found.

This outcome is a stark contrast to the past. Palloh Hill, where the mill stands, was believed to host the spirits of the ancestors of Lower Kulu. People consulted the hill for a good harvest and other things. Similarly, Sleni Creek was believed to give women children in addition to being the source of water in the vicinity. Now both landmarks are being used as part of GVL’s irrigation system, supplying water to palm nurseries.

Amid these issues, GVL has failed to provide hand pumps for the people here. It has been over three years since GVL began to build it, according to locals. This violates GVL’s environmental permit and MoU with Tarjuwon, which requires the company to build hand pumps in affected communities with over 150 people.

“Since GVL could not complete the hand pump… and we did not have any water to wash with or drink, we decided to use it as a well, instead of hand pump,” said Ophelia Kumon, a resident of Wieh Town. She spoke at the unfinished hand pump just a stone throw from the back of the mill. She and other residents use a bucket attached to a rope to draw water from the well.

But safe drinking water is not the only issue. Swarms of flies are also another nightmare for Wieh Town. Buzzing flies enter homes and sit on villagers’ foods threatening their health.

Though the open wastewater attracts flies, the largest swarms of the insects are mainly attracted to the palm husks. They contain hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and sulfur, scientists say. While the other gases are odorless, sulfur smells like rotten eggs, apparently explaining why it attracts so many flies. The environmental audit found that wastewater was likely to emit a gas with a foul odor that was harmful to the people and the planet.

“We are really suffering here. The fly situation is now worse to the extent that you have to buy fly [repellent] to be on the safe side,” Jarteh said.

“The rain is coming and the flies will be on our food and we will have to eat it,” he added.

‘By the grace of God’

Smoke from the mill is yet another problem, according to residents. Townspeople said at times they did not recognize the person next to them.

“Sometimes when GVL puts the machine on, there is certain smoke that comes out which can spread over the whole town,” Robert Maye, a resident of Wieh Town said. “It smells so bad to the extent that if you don’t have strong resistance, you can’t live in this town. It is affecting us greatly.”

The DayLight could not independently verify that claim and another regarding noise pollution. However, elevated images shot by a drone show white smoke billowing persistently from the chimneys of the facility, something the audit uncovered. It also said the mill discharged thick, black smoke that lasted about five minutes.

GVL sidestepped direct questions The DayLight posed to it on the issues. However, in a press release after the newspaper published two investigations regarding the company’s operations, GVL claimed it took pollution and communities’ grievances seriously.

“We also ensure that water testing is done annually by an independent party as required by EPA regulations,” the release said. “Recent assessments conducted in 2023 and 2024 did not identify any issues.”

But the environmental audit report proves those claims are false and misleading. Like the pollution issue, the report found GVL did not address locals’ complaints, urging it to take urgent actions.

In Wieh Town, residents continue to brace themselves as their pollution war wages on.

Jarteh said, “We are just surviving by the grace of God.”

The Green Livelihoods Alliance (GLA) provided the funding for this story. The DayLight maintained editorial independence over the story’s content.