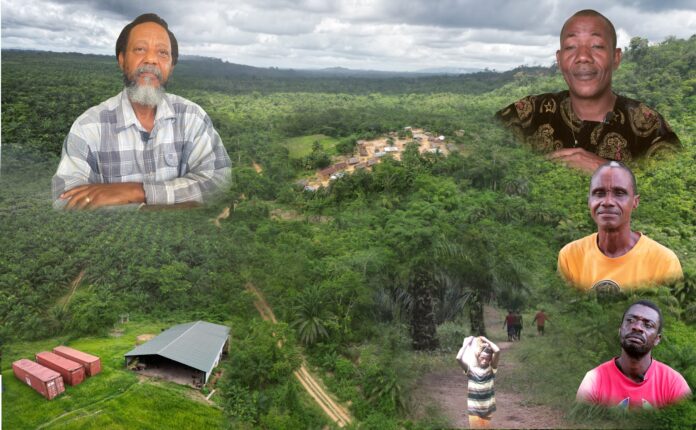

Top: Liberia’s proposed deal with Blue Carbon of the United Arab Emirates is expected to cover over a million hectares of rainforests. Graphic by Rebazar Forte

By James Harding Giahyue

- Liberia and Blue Carbon should halt carbon credit negotiation, as the deal violates Liberian laws, according to a group of international NGOs

- The deal must comply with procurement, forestry and land laws, and seek the consent of local communities to continue

- The NGOs say the United Arab Emirates wants to use the agreement to “greenwash,” its own carbon emissions

- NGOs say the “vague” and “secret” deal is not good for the Liberian government and indigenous communities and undermines Liberia’s own climate targets

MONROVIA – A group of 16 international NGOs has called for a halt to an ongoing carbon credit deal between Liberia and Blue Carbon of the United Arab Emirates until it complies with Liberian laws and is clear on how the country and local communities would benefit.

The Liberian government and Blue Carbon negotiating the terms of the agreement. The government wants to give the company over 1 million hectares of land over 30 years for US$50 billion, according to a draft memorandum of understanding (MoU).

But the deal would be a violation of Liberia’s procurement forestry and land laws, the statement said.

“We, therefore, call upon the Government of Liberia and Blue Carbon to halt these negotiations until there is clear evidence that the contract is in line with Liberian law,” the NGO said in a statement released last week.

“This risks the livelihoods of up to a million people. It would also extinguish community land ownership in the selected areas while violating peoples’ legal right to provide free, prior and informed consent for any developments on their land,” it added.

In March, Liberia and Blue Carbon penned the agreement, in which Liberia is expected to lease Blue Carbon a number of protected areas and proposed protected areas to solely manage. Blue Carbon’s mission is to use bilateral agreements to help reduce carbon emissions globally, according to its website.

“This bilateral association marks another milestone for Blue Carbon to enable government entities to define their sustainable frameworks and help transition to a low-carbon economical system…,” Sheikh Ahmed Dalmook Al Maktoum, Blue Carbon’s chairman and senior member of UAE’s Royal Ruling Family.

Minister of Finance and Development Planning Samuel Tweah, Jr. said the deal marked an “era of sustainability.”

But local communities that would be affected by the deal have not had a say in it, a violation of the National Forestry Reform Law, the Land Rights Act and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, an instrument Liberia has signed into law. All three legal instruments require villagers’ free, prior and informed consent in concessions negotiations.

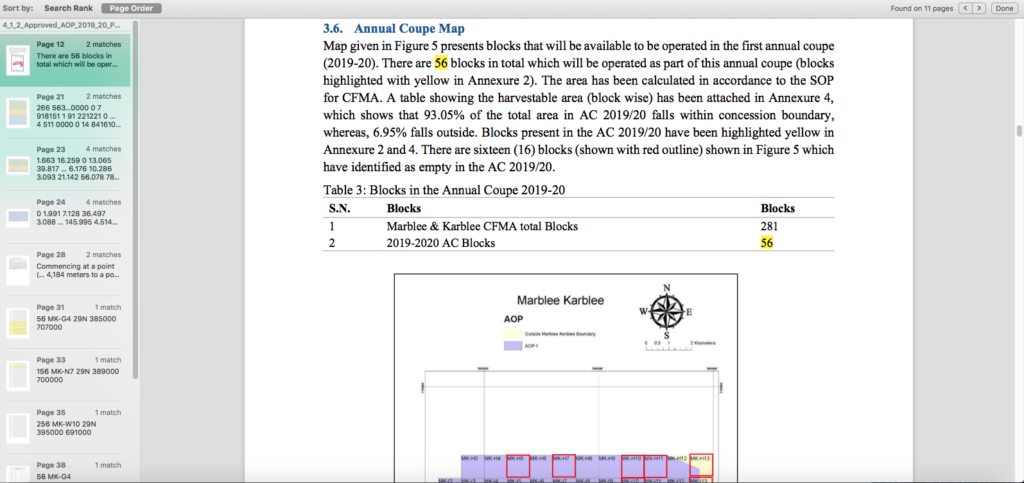

Furthermore, more than 1 million hectares of rainforests render the MoU illegal. Liberia’s forestry law limits forest concessions to 400,000 hectares.

The NGOs call on the parties to consult communities and incorporate their benefits into the deal. They include Fern, Friends of Earth Netherlands and the Environmental Investigation Agency.

“It should also prove that the financial support provided protects threatened forests and restores degraded forests with strict monitoring and control mechanisms in place,” the statement said.

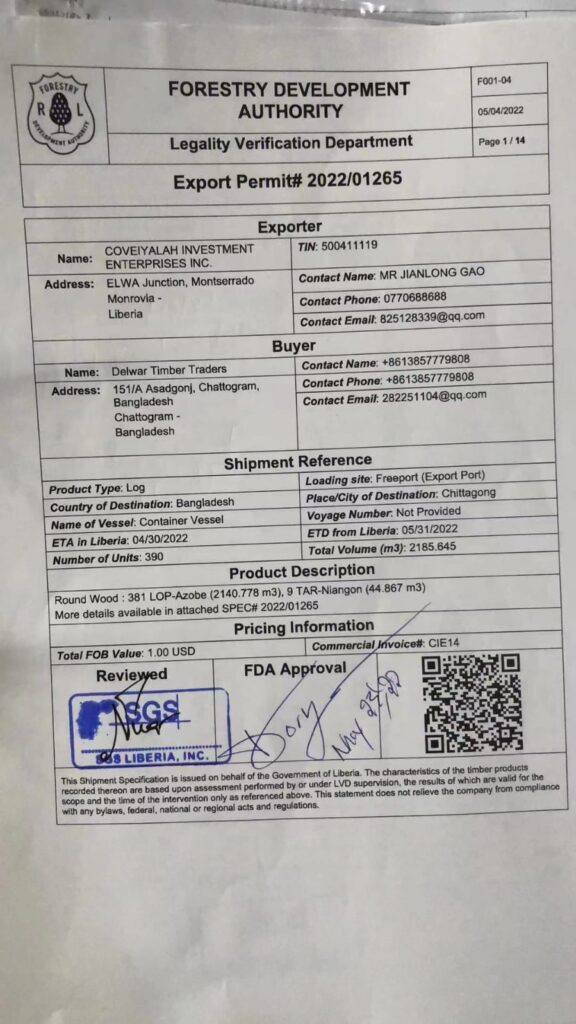

The proposed deal would also break the Public Procurement and Concession Act because there was no bidding.

The Liberian cabinet endorsed Blue Carbon as a sole source on June 3, based on a letter from the Managing Director of the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) Mike Doryen to the Public Procurement and Concession Commission (PPCC).

In the letter, Doryen asked PPCC’s Officer-in-Charge Stevenson Yond to approve Blue Carbon as a sole bidder for the concession.

Section 55 of the procurement law allows for “sole sourcing,” except in an “extreme urgency,” and other instances, none of which the deal qualifies for.

Section 101 of the act also provides for a sole source but limits it to a bidder with specialized expertise only that bidder can provide. It also requires the concession to involve research only the bidder can undertake or it would be against national security for a competitive bidding process. However, none of those instances fits Blue Carbon, established only about a year ago and had not traded in the carbon market before.

Doryen did not immediately respond to The DayLight’s queries for comments.

‘Greenwashing’

The international NGOs accused the UAE, a country that has one of the highest emission rates in the world, of using the Blue Carbon deal to offset its own greenhouse gas emissions. In other words, the Arab nation, which hosts the United Nations climate change conference later this year, allegedly wants to invest in Liberia’s rainforest and continue its energy, oil/gas and infrastructure projects.

“The revenue model described in this contract generously allows for that,” the statement said. “This contract seems to give Blue Carbon, a private UAE company, the authority to act on Liberia’s behalf to negotiate [United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change] Article 6 rules.” Article 6 of the Paris Climate Agreement talks about carbon credits and trading.

The NGOs critique the draft document’s intent to award Blue Carbon the exclusive right to use carbon credits. Blue Carbon would exclusively manage the forest resources, including reforestation, conservation and ecotourism, according to the MoU.

“If they are sold, Liberia will not be able to use the carbon credits to meet its own climate targets,” the statement said. Liberia committed at the Paris Summit to reduce deforestation by 50 percent by 2030.

“It is unclear what the benefits for Liberia and its communities will be. The contract is confidential and extremely vague, and a [MoU]… signed in March this year has not been widely discussed,” it added.

The statement followed criticisms from national NGOs and the Liberian People’s Party.

The DayLight has reached out to Blue Carbon for comments.