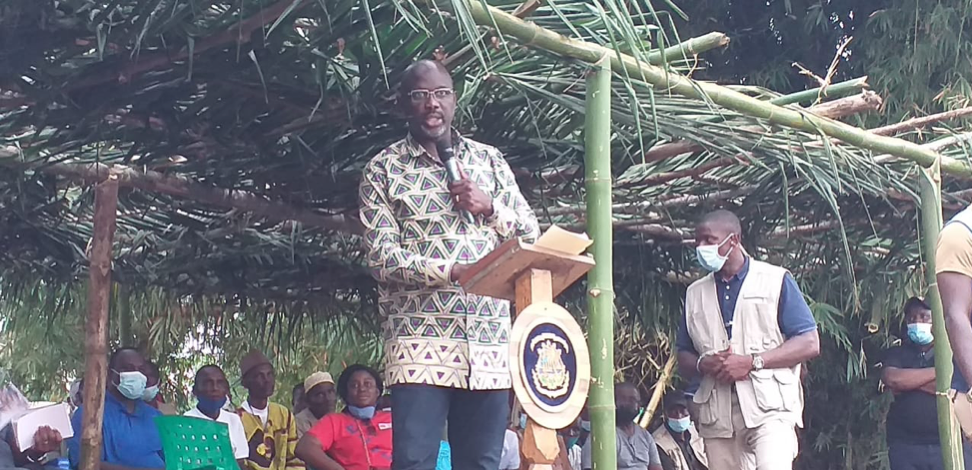

Banner Image: President George Weah violated the Land Rights Act by accepting 1,500 acres of land in Gbi-Doru, Nimba County. Picture credit: The Analyst

By Varney Kamara

- In 2020, the people of the Gbi-Doru District in Nimba County gave President George Weah 1,500 acres of land he is using for agricultural purposes

- Despite being his maternal hometown, Weah violated the Land Rights Act of 2018, as the community does not meet legal requirements to transfer ownership of a portion of its ancestral land.

- In February, the remote district petitioned Weah to grant them a district status and an official recognition of their tribe to end years of lack. Chiefs and elders The DayLight interviewed said it was the reason they gifted him the land.

- A Legal expert said the President also violated the Code of Conduct, as accepting the land amounts to a conflict of interest

DORGBOR TOWN, Nimba County – President George Weah violated the Land Rights Act of 2018 when he accepted 1,500 acres of farmland from people in his maternal homeland in Nimba County, an investigation by The DayLight has found.

Chiefs and elders of Gbi-Doru in the Tappita District last year gifted Weah the land, the size of 1,136 football fields, which produced 550 bunches of rice last year, villagers said. It was not clear how much land the district has in total.

“When [Weah] leaves power, the land belongs to him because he is our son. He is our nephew and he’s controlling the whole nation,” said Foster Dorgbor, 41, Town Chief of Dorgbor Town, the closest community to the land. “He owns more than that. We are just testing him yet.

“You cannot have a hunter and don’t have soup in your house,” said Chief Dorgbor. “Our nephew is controlling the whole nation now, so we said ‘Let us draw his attention that he is from this side.’”

Having accepted the land, the President violated the milestone law, one of the first legal instruments he signed upon assuming office in 2018. Acclaimed worldwide for its recognition of customary land rights, the law lays out a legal process through which a community can transfer ownership of their land. A community must first identify itself as a landowning one, demarcate the boundaries with its neighbors, establish its members, draft bylaws, set up a community land development and management committee (CLDMC), and draft a land-use plan. Only the collective members of the community—including women and the youth—have the right “to approve the sale, lease or donation of customary land.” Gbi-Doru has not even started that process.

“Under the Land Rights Act, George Weah is entitled to possession and ownership of land in Gbi-Doru District for residential purposes, since he is a community member by virtue of Gbi-Doru being his maternal home district,” said a lawyer, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution. “However, if it is not for the purpose of taking title to a customary land as a residential area, the [law] forbids any act of purchase, holding or permanently alienating any portion of customary land until after the expiration of fifty years from the effective date of the [law].”

Residents told The DayLight they were unaware of the law.

“We don’t know anything about Land Rights [Act] here. No land rights activists have come here,” said Abednego Wlaryee, the town chief of Tiah’s Town, though he told The DayLight he was in River Cess County when Gbarsaw and Dorbor Clan completed the requirements to obtain its ancestral land ownership.

The Liberia Land Authority (LLA), which oversees the land sector and implementation of the law, did not respond to queries on the matter up to the time this story was published. We will update this article once it does.

‘Grant Us Independence’

The lawyer The DayLight interviewed said Weah was also liable for a conflict of interest, a violation of the Code of Conduct for all Public Officials and Employees of the Government of the Republic of Liberia. The law defines conflict of interest as “when a public official, contrary to official obligations and duties to act for the benefit of the public, exploits a relationship for personal benefit.”

“The argument could be that the 1,500 acres gift to the president by the Gbi-Doru community is well deserved because the community is his maternal home. The question then is: Why now and not before he was a president?” The lawyer said. “Obviously, if it was not but for his office, this gift could have never been a deal between the president and the people of Gbi-Doru. Evidentially, the President is using his office or official position to pursue his private interest, which is most likely to yield a conflict of interest.”

It was only a year after they gifted him the land that chiefs and elders of Gbi-Doru petitioned Weah to give the district a county status and make its language official on his visit there as part of a nationwide tour. The birthplace of Weah’s late mother, Anna Quayeweah, the district has been neglected by successive governments, lacking roads, schools, hospitals and other public utilities.

In the last decades, it has embarked upon campaigns to end its misery. First, to be returned to River Cess after a tax row in 1938 saw then-President Edwin James Barclay place the district under Nimba County. With the quest highly unlikely achievable, the district—which has a population of 7,744 people, according to the 2008 National Population and Housing Census—has turned its attention to a more ambitious goal.

“Please grant us independence, independence in the form and fashion of a county status. Please grant the Gbi Tribe an official and statutory recognition so that Gbi will be the 17th official tribe of the Republic of Liberia,” their petition read at the time.

“We are left behind in the Republic of Liberia,” said Paramount Chief Saturday Thomas in an interview with The DayLight through an interpreter. “Our action was to tell the President we are Liberians and deserve attention. We need our own superintendent and representatives who will pay attention to us.”

Weah asked the chiefs and elders to be patient. “The Constitution gives you the right to such demand, but this can be done through an act of legislation,” Weah told residents at the time. “For too long you have complained, and it was prudent to listen and grant your desire in accordance with the law. I want you to exercise patience and engage relevant authorities, including the Legislature to grant this request.” He toured the controversial farmland, with pictures and videos of him brushing bushes going viral on Facebook.

Things have not worked as villagers expected. Farming activities on the land this year were interrupted by prolonged rainfall. And the Liberia Agency for Community Empowerment (LACE) halted a 22-bedroom-clinic project for not meeting the standard of a health facility, according to villagers in Dorgbor Town, where the construction is ongoing.

“LACE stopped the project and promised to get back to us when things are finalized,” Michael Teah, the youth chairman of the community and its representative of the project. LACE did not respond to queries for comments on the project.

‘Elite land-grab’

The controversies over the land come at the time land rights campaigners are flagging a growing number of “elite land-grabs” in a state whose land history involves several battles with rural communities as far back as its establishment in the early 1820s. Last month, the Civil Society Land Rights Working Group (CSO-LRWG) criticized the Liberia Land Authority for being too slow to formulate regulations for the implementation of the law, three years after its creation. The group warned of countrywide land conflicts, calling on the Liberia Land Authority (LLA) to speed up the development of regulations to enforce the law.

“This is an important case that should trigger serious discussions about implementing the land rights law, starting with drafting regulations,” said Ali Kaba, one of the crafters of the law and now a Ph.D. scholar in development studies at the American University in Washington D.C.

“Elite land-grab undermines the intent of the Land Rights Act,” said Nora Bowier of the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI). “It worsens poverty as it deprives communities of their rights to a fair deal and economic benefits from their land and resources.”

The Executive Mansion declined to comment on the land matter. It recommended The DayLight to the Ministry of Information, Cultural Affairs, and Tourism, which, likewise, refused to comment on the matter.

The story is part of The DayLight’s Land-grab Reporting Series.