Top: In one of his first acts after being appointed Managing Director of the Forestry Development Authority, Rudolph Merab signed an illegal export of 797 logs for West Water Group (Liberia) Inc. The DayLight/Harry Browne

By James Harding Giahyue

Editor’s Note: This is the first of a series on the Forestry Development Authority’s approval of illegal timber exports.

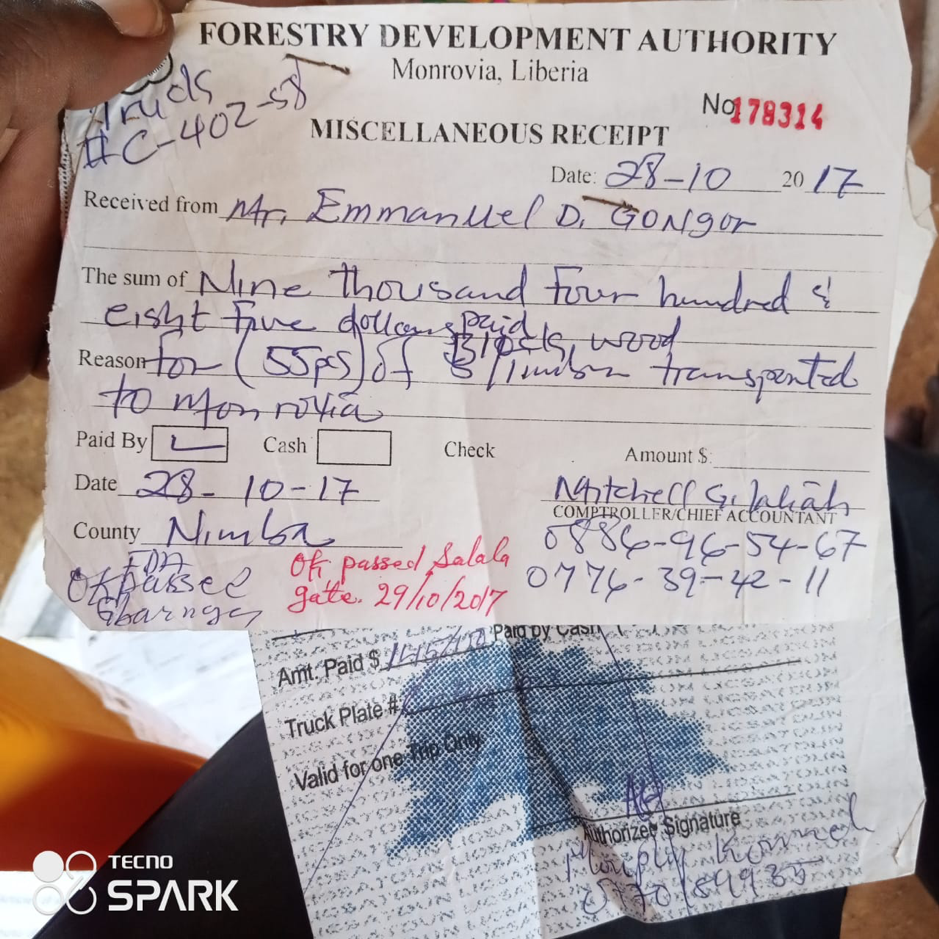

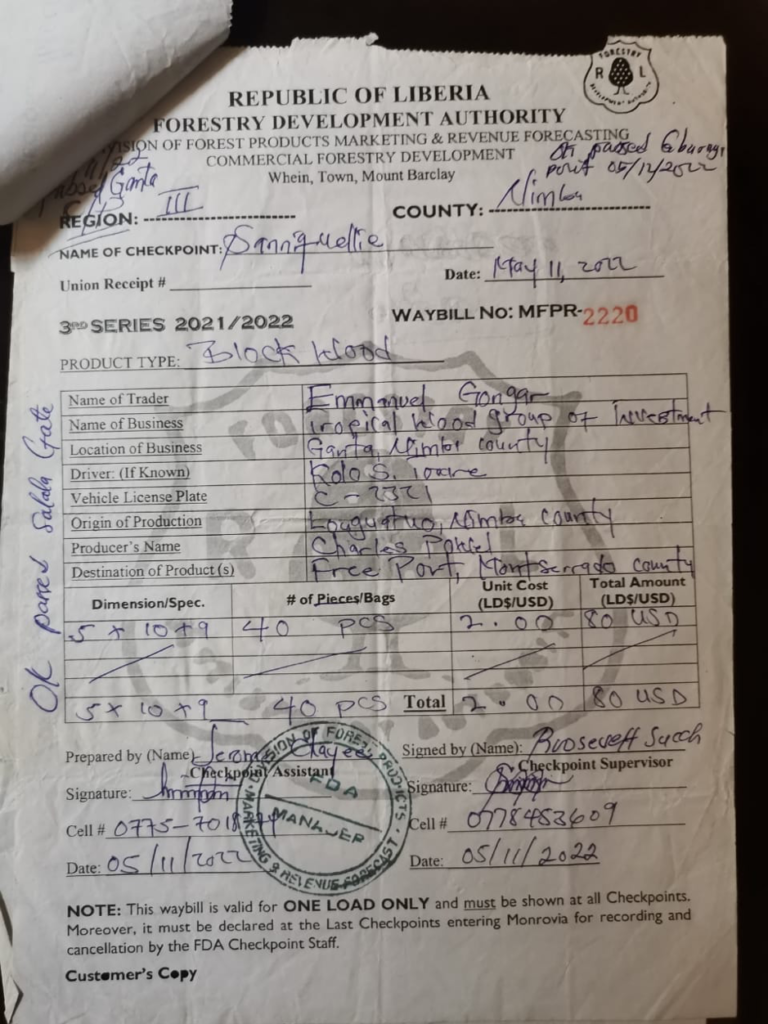

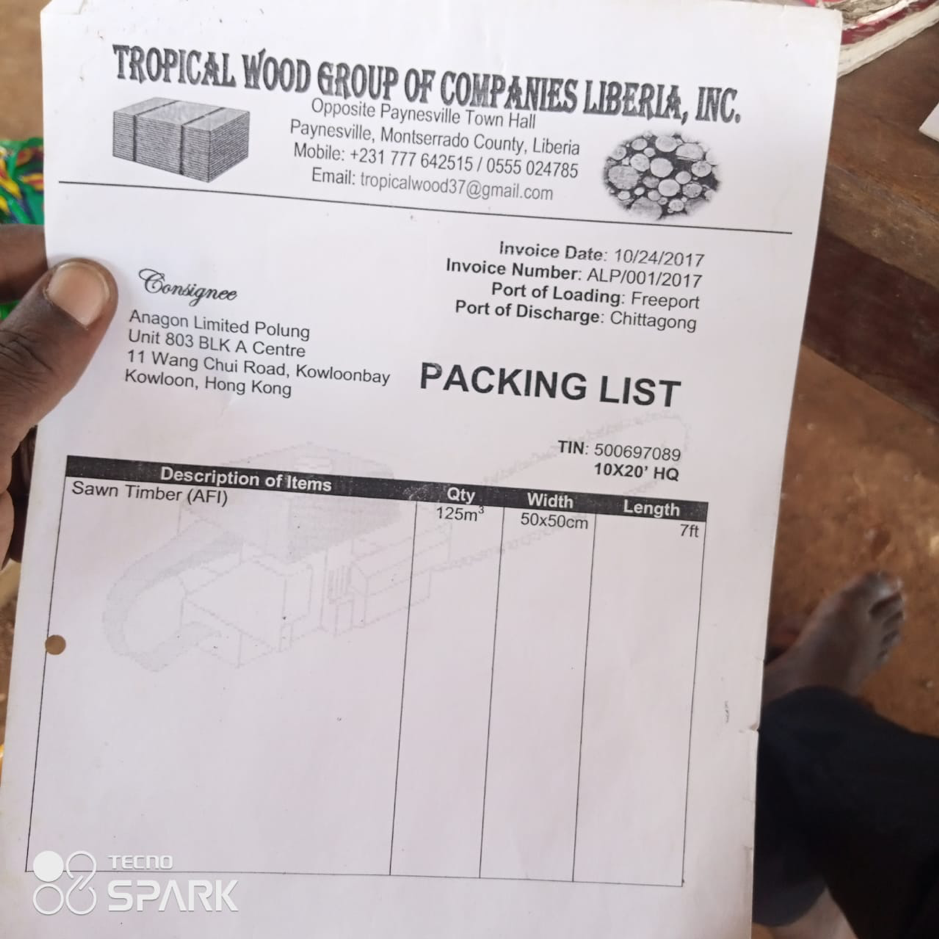

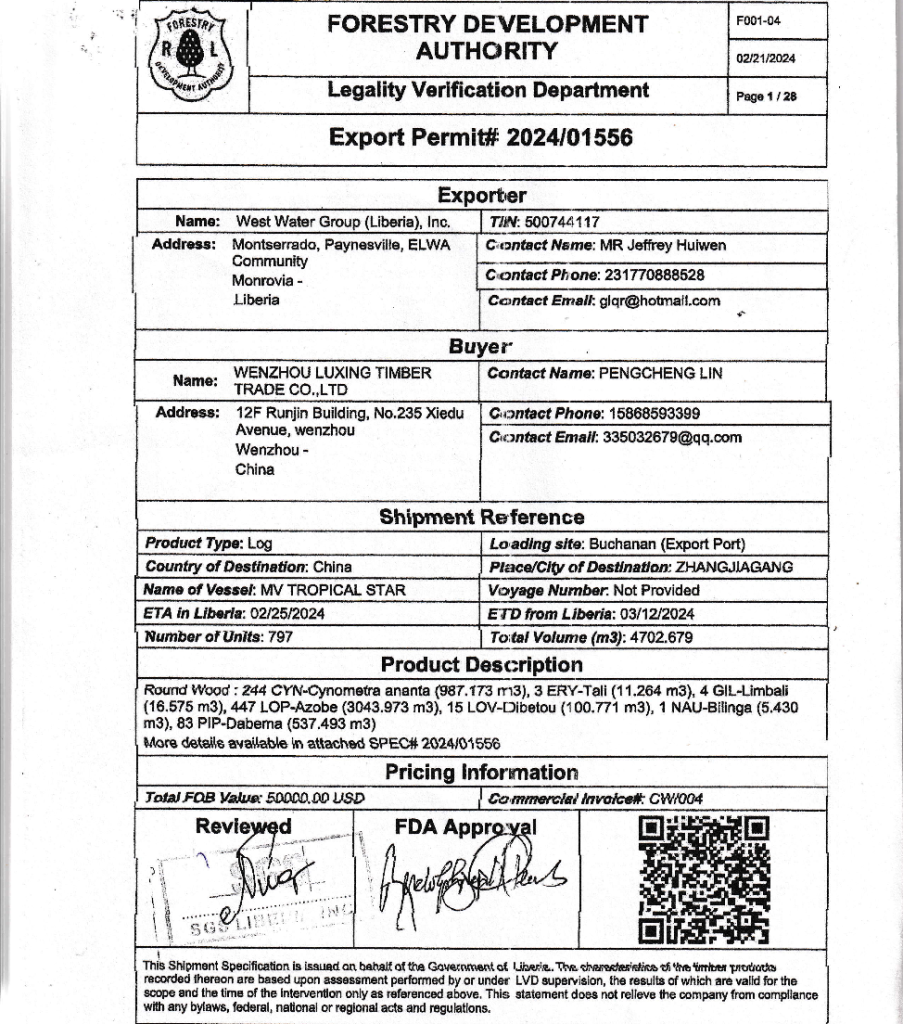

MONROVIA – The Forestry Development Authority (FDA) approved the export of 797 logs, valued at an estimated US$923,441, despite being aware that over half of the timber had been illegally harvested. The illegal shipment was one of the first acts of Managing Director Rudolph Merab—a serial logging offender—since he became the unlikely head of the forestry regulator.

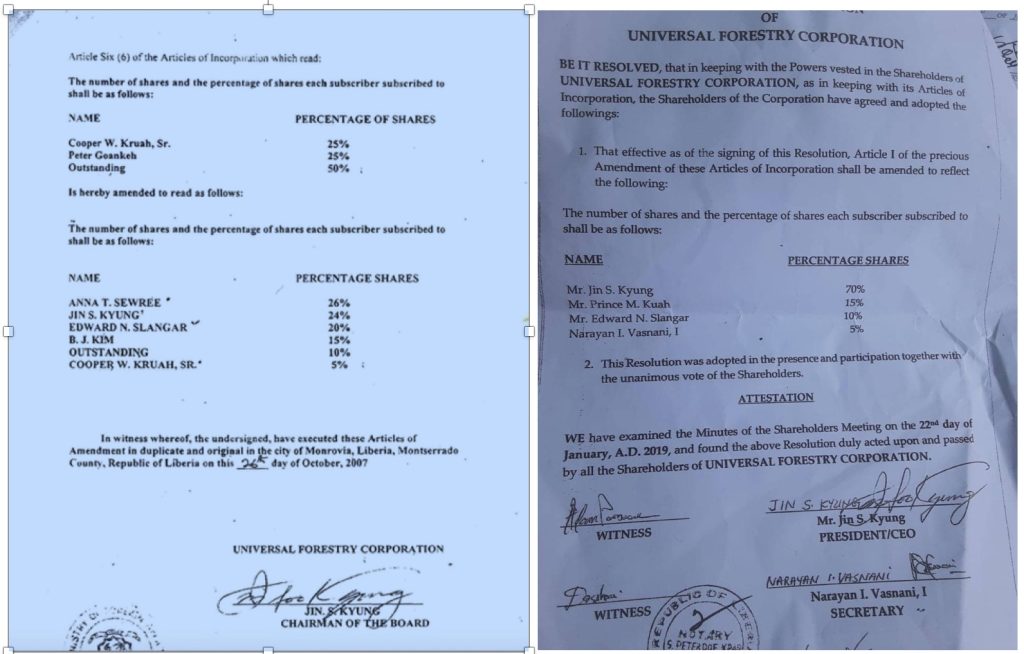

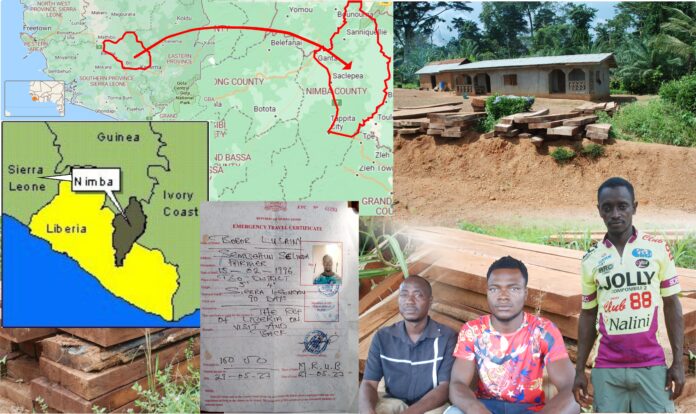

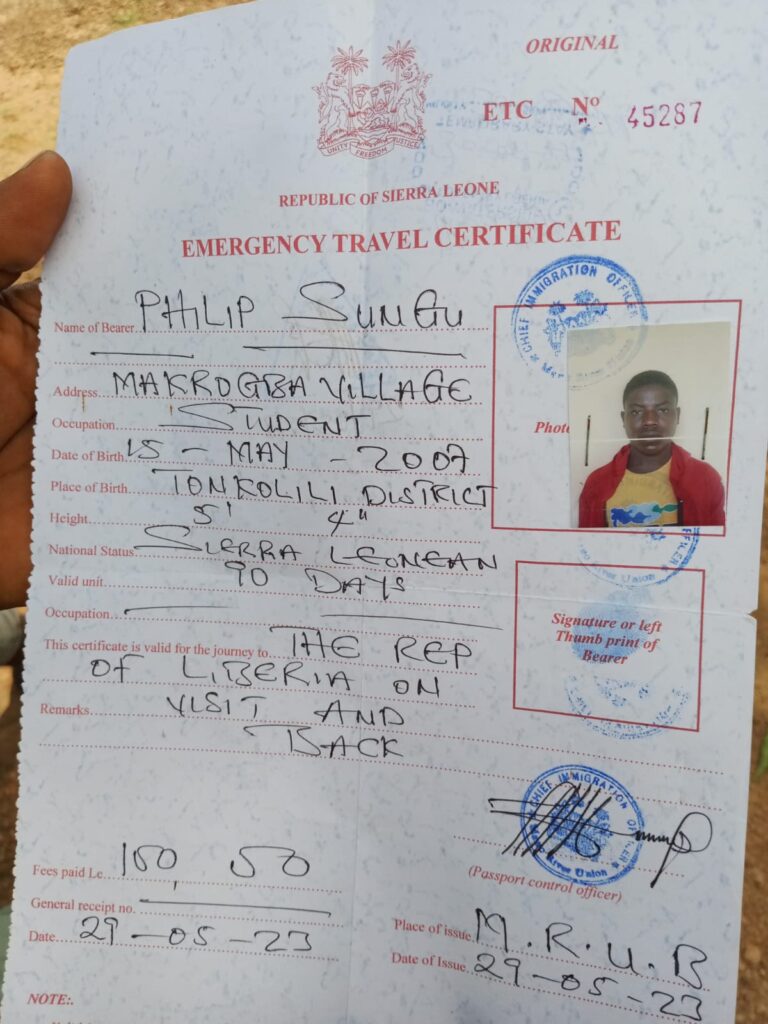

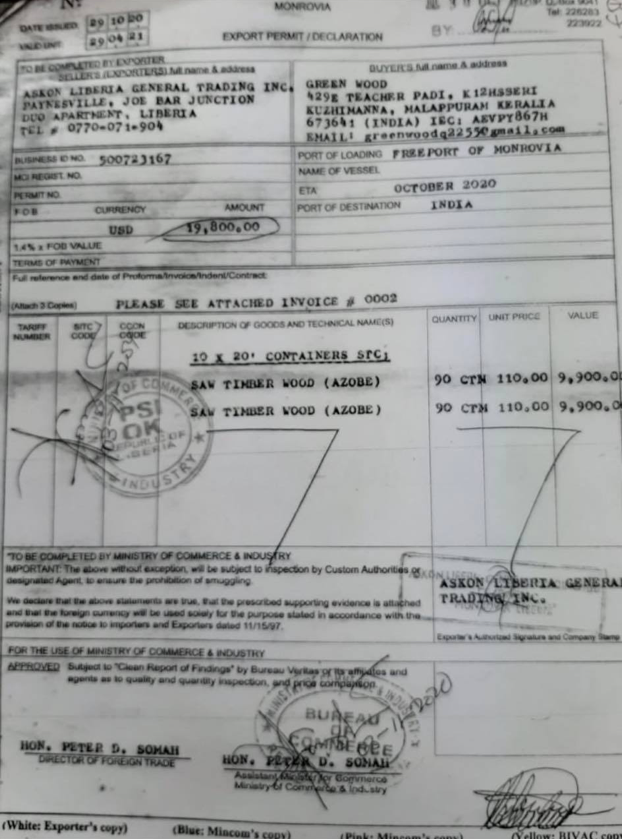

The export permit and a National Port Authority reconciliation report show that West Water Group (Liberia) Inc., which operates in Grand Bassa and Nimba Counties, owns the shipment. Merab had approved the export barely two weeks after his appointment in February, according to the permit.

The 4,702.679 cubic meters of logs were loaded onto M/V Tropical Star, a ship flying under the Malaysian flag. The vessel departed the Port of Buchanan on March 16 bound for China. Marine Traffic, which provides information on the movement of ships, reports that the ship is due in China on May 16. Wenzhou Timber Group Co. Ltd, the Chinese state-owned firm that deals in timber and other trades, bought the consignment, according to the permit.

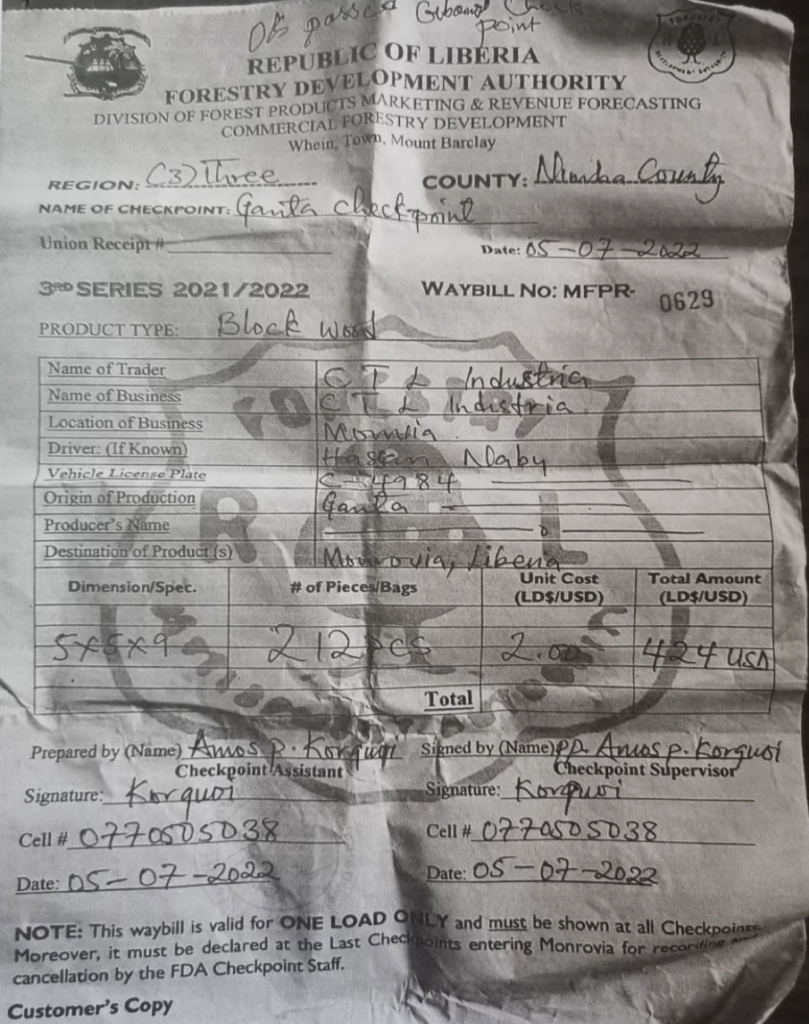

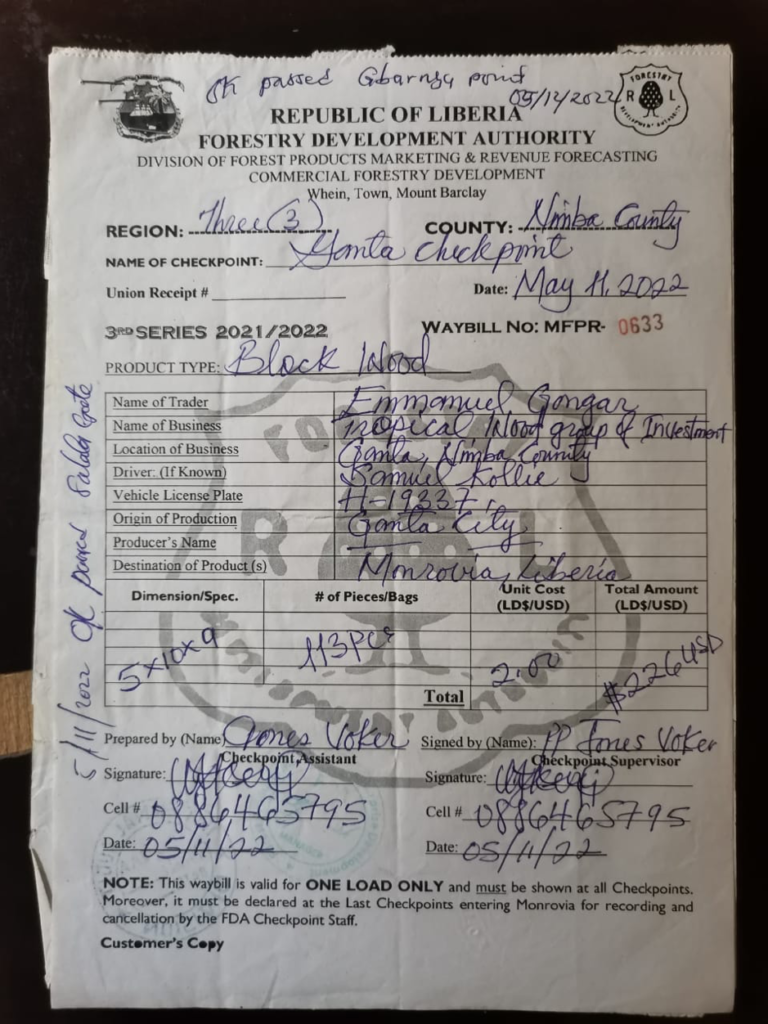

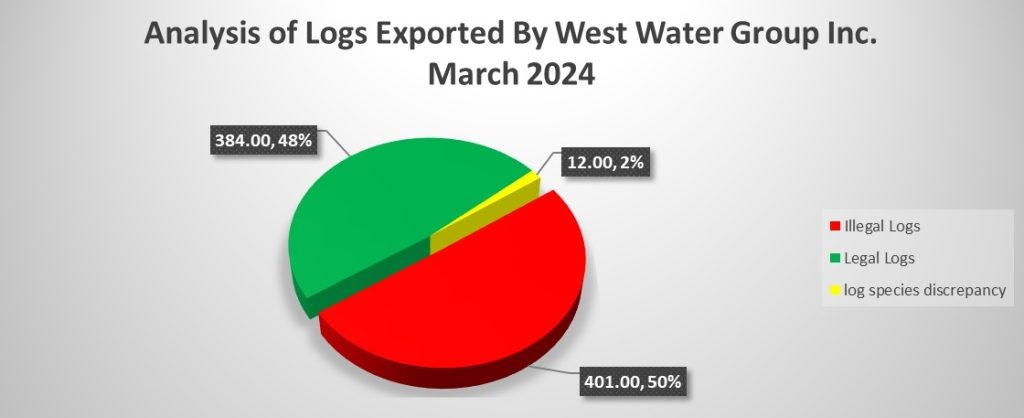

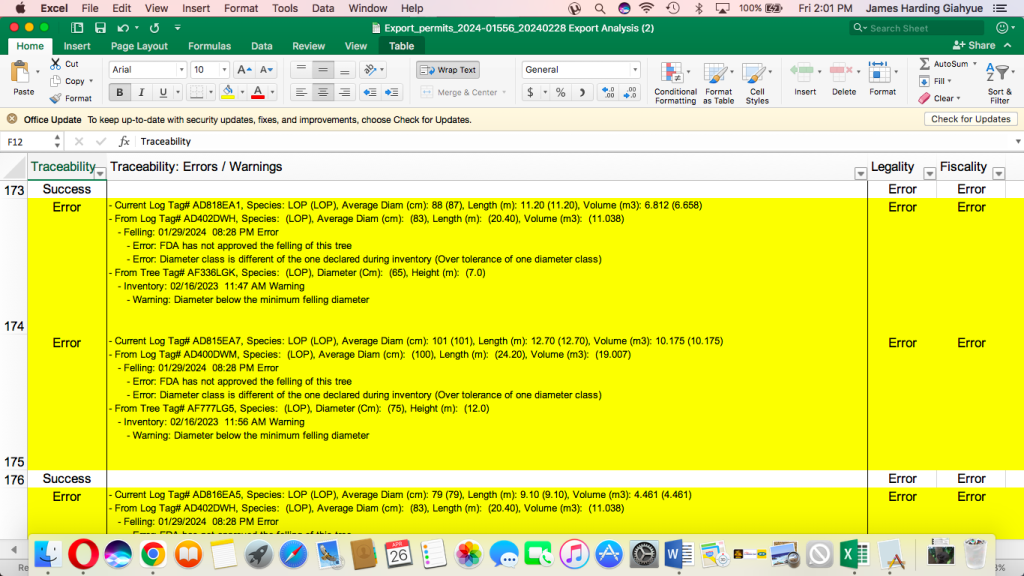

But an analysis of the consignment FDA’s computer system generated by, obtained by The DayLight, identified 401 logs, or 50.3 percent of the consignment as illegal logs. The LiberTrace system tracks logs from their origin to their final destination. Programmed automatically to flag noncompliance, it is a crucial part of forestry reform following years of corruption and mismanagement. SGS, a Swiss verification firm, created LiberTrace in 2014 and turned it over to the FDA five years later.

A document from the FDA’s legality verification department (LVD) provides a peep into how Merab approved the export. It reveals Gertrude Nyaley, the Deputy Managing Director for Operations, who headed LVD at the time, endorsed the export.

“[Managing Director Merab], please approve [West Water’s export permit] as per the analysis and payment made,” Nyaley wrote to Merab.

Nyaley appeared to have skipped the red flags LiberTrace raised. “Out of the 797 logs, 50 percent are traceable with red label because of diameter [issues]. Two percent is also traceable relating to species. And 48 percent over tolerance,” Nyaley added.

On the contrary, the analysis shows that the FDA had not authorized the harvest of some of the logs. Others were either immature, originated from different sources or had other issues, violating several forestry statutes.

‘Vulnerable’

The FDA had not approved the harvesting of 180 of the 401 problematic logs, according to the Liber Trace analysis.

Of that 180, 160 logs were ekki wood (Lophira alata) that did not meet the legal diameter ekki wood is listed as “vulnerable” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a UN-recognized body that promotes sustainable use of natural resources. The DayLight manually verified the permit that details each of the logs exported. Some even measured 60 centimeters, 20 centimeters less than the required dimension, known in forestry as the diameter cut limit.

No penalties

Approving the West Water shipment shows Merab, an outspoken critic of forestry regulations, ignored various legal frameworks, and the violations LiberTrace flagged. The main function of LiberTrace is to keep illegal logs from the FDA’s chain of custody system, which covers everything from harvest to export. That, in turn, rids national and international markets of illegal timber and timber products.

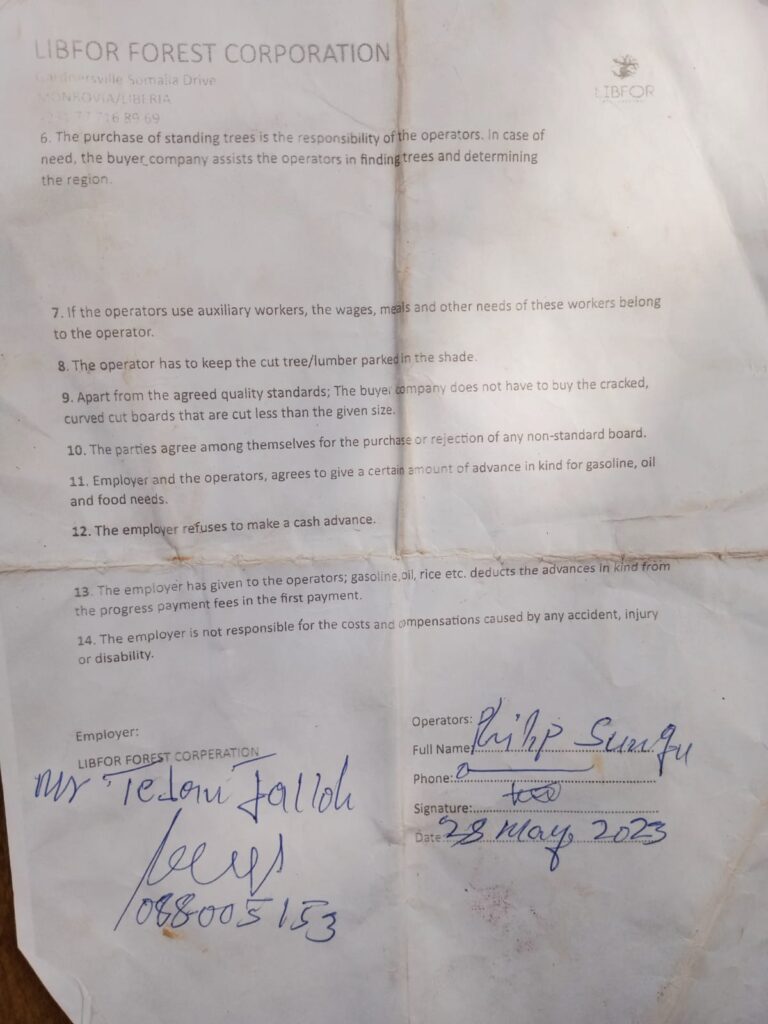

Unauthorized harvesting, cutting smaller trees, and false declaration of tree species all carry a fine or a penalty. Unauthorized harvesting, for instance, carries a fine of twice the value of the species of logs unauthorizedly felled, under the Regulation on Confiscated Logs, Timber and Timber Products. Mr. Huiwen, West Water’s owner, did not respond to email and WhatsApp queries for comments.

SGS, which comanages LiberTrace alongside the FDA, reviewed the permit but did not disapprove it.

Theodore Aime Nna, SGS’ forestry project manager, did not return questions for comments on this story. Nna said he was “not currently around” and would be available in 18 days for an interview. Nna, who took a swipe at The DayLight in two immediate emails, did not reply to the newspaper even 21 days thereafter.

‘Major traceability errors’

In his response to The DayLight’s queries on Wednesday, Merab said the red flags LiberTrace raised did not “automatically point to traceability or legality issues,” and were, in fact, “normal occurrences.”

Merab said the 12 logs that were different from the one declared during inventory might have been mistaken. “The logs recorded in that specific export permit are consistent with the approved physical logs,” he said, without any evidence.

On undersized logs, Merab suggested that the logs LiberTrace red-flagged in this category were based on tree inventory data, not the ones that were felled or in West Water’s log yard.

This likely mix-up is commonplace in forestry. However, the details of the logs on the export permit do not support Merab’s explanation. The document repeats the very things LiberTrace identified as a warning or an error. If the log data had been verified as Merab claimed, the changes would have been reflected on the permit’s spec.

Merab offered another broad, textbook justification for the ekki logs LiberTrace picked up as immature.

“This happens because logs have a conic shape with a bottom diameter higher than the top diameter. In the case of a crosscut of that log, the diameter and the length will reduce mainly at the top part of the initial log. Again, these are normal occurrences,” he said.

What Merab referenced is called the diameter at breast height cutting limit or DCL in the Guidelines for Forestry Management Planning. But it only measures a standing tree’s trunk or the tree butt end, not the top end or a crosscut log. It is measured at the height of an adult’s breasts.

Furthermore, the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) which writes the bible for the global wood trade describes ekki logs as cylindrical, not conical.

Merab sidestepped the question regarding the FDA’s disapproval of the felling of a significant amount of West Water’s logs.

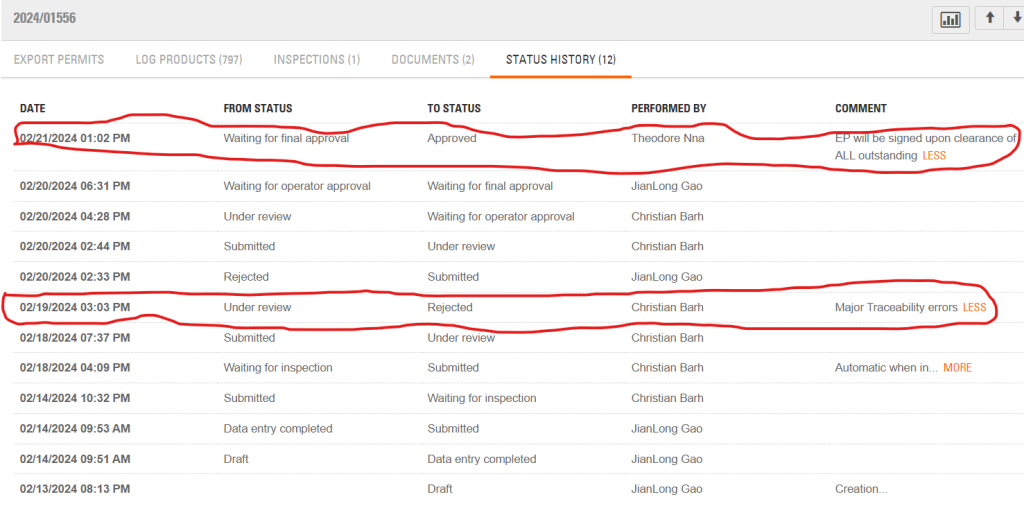

But, remarkably, The DayLight obtained a LiberTrace screenshot detailing the history of the status of the export permit. It reveals that the FDA approved the export permit less than 48 hours after LiberTrace identified the “major traceability errors.” For an agency perennially plagued by financial, logistical and manpower constraints, that was too short a time to correct hundreds of legality issues surrounding the consignment.

A Serial Forestry Offender

The West Water illegal export has added to Merab’s profile as a serial forestry offender.

His last known illegality was his participation in the infamous Private Use Permit Scandal in which his company Bopolu Development Corporation (BODECO) was illegally awarded 90,527 hectares of forest in Gbarpolu in the 2010s.

Before that, Merab traded “blood timber” alongside former President Charles Taylor, which fueled death and destruction in the Mano River basin between the 1990s and early 2000s, according to British NGO Global Witness.

The Regulation on Bidder Qualifications partially debars Merab and other wartime loggers from conducting forestry activities in Liberia, except if they meet special requirements. It, however, is unclear whether the regulation blocks Merab from heading the FDA.

[Gerald Koinyeneh of FrontPage Africa and our editor-at-large Emmanuel Sherman contributed to this report]

To get the estimated value of logs, The DayLight multiplied the total volume of each species of logs in the consignment by the FDA-approved price and summed up the products.