Top: A poster showing former Managing Director Mike Doryen and his deputy Benjamin Plewon, Edward Kamara and chainsaw milling activities. The DayLight/Rebazar D. Forte

By Esau J. Farr

MONROVIA – Titus Buah was very excited about his new assignment as the supervisor for a checkpoint in Big Joe Town, Grand Bassa County. It was a busier, bigger and more beneficial assignment for a checkpoint contractor with the Forestry Development Authority (FDA).

But Big Joe Town was unlike his previous assignments. In Saclepea and Sanniquellie, Nimba; Belefanah, Bong; and Zwedru, Grand Gedeh, he sent fees he collected from plank dealers to a mobile money number assigned to the FDA. Now, he had to report to the FDA and Benjamin Plewon III, then Deputy Managing Director for Administration (DMDA).

“The DMDA himself called me to report the money. He gave me seven different numbers I used to send the money on,” Buah said.

“I was required to produce L$50,000 from the first to the 15th of every month and another L$50,000 from the 16th to the end of the month,” Buah added without providing any evidence.

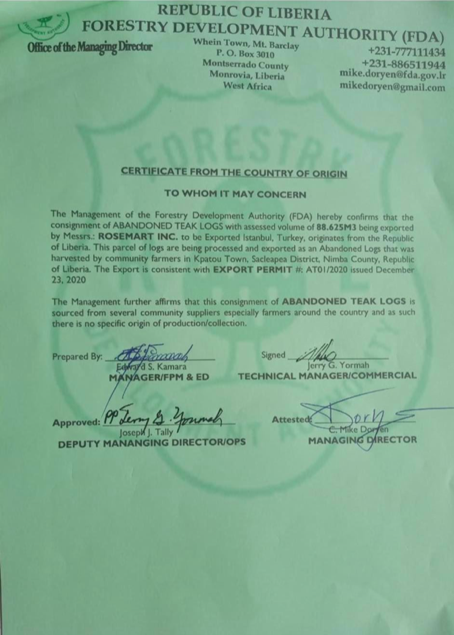

In the last six years, Buah and other checkpoint contractors collected an estimated US$2.95 million, according to records of the Liberia Chainsaw and Timber Dealers Union (LICSATDUN). The record shows that the amount was collected from five of the dozens of checkpoints countrywide, and did not include a US$120 plank businesses pay.

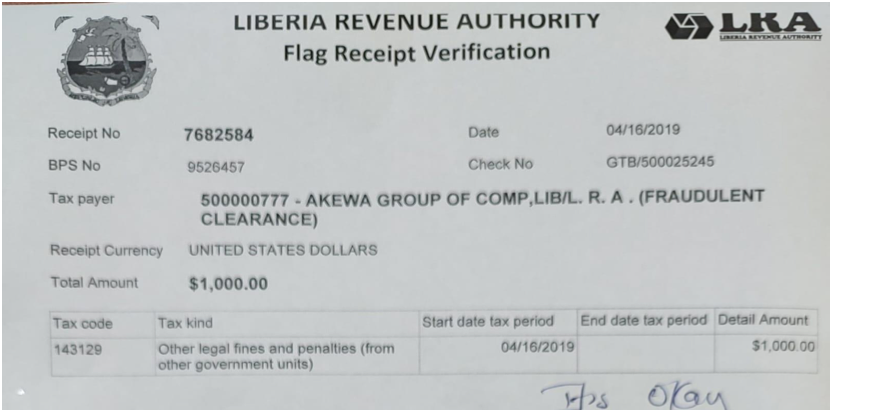

But there is no known trace of how the FDA used the money—not in reports by the Liberia Revenue Authority (LRA), which collects the government’s revenue, or the Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (LEITI), which publishes public payments.

The last administration of the FDA reported US$2,500 and L$7 million from chainsaw milling for 2023, according to sources familiar with that report. That is a wide gap from the US$464,325 chainsaw milling generated last year, based on LICSATDUN’s records.

The Managing Director of the FDA Rudolph Merab did not respond to questions for comments nearly a month later.

‘Somehow embarrassing’

The lack of accountability and transparency in the use of the funds bothers LICSATDUN, which has 250 registered members across the country.

The union has exerted efforts in the last six years to formalize chainsaw milling, which contributes between US$1.4 and US$1.9 million annually to the government, according to a 2017 report. Though largely unregulated, chainsaw milling is the sole timber supplier in local markets. The report found the subsector values between US$30 million and US$41 million.

In 2019 the LRA opened a sub-office at FDA’s headquarters in Paynesville and started to collect US$0.60 on every plank transported. However, the next year, the tax agency closed the facility after it became too costly to maintain, according to Kaihenneh Sengbeh, the LRA’s manager for communications, media and public affairs. Sengbeh said the facility rarely collected any taxes.

In the absence of the failed scheme, chainsaw millers continue to pay US$0.60 to the FDA, which manually issues them waybills or authorization to transport timber. This has fueled corruption and given rise to the trafficking of block-shaped timber commonly called kpokolo.

“If [the] LRA is involved, then we feel that this money is channeled through the government’s revenue,” said Julius Kamara, LICSATDUN’s president.

“It is somehow embarrassing to our members. If the FDA comes out to say that ‘You people are not paying a cent to government,’ the only [defense] we have is the waybills.”

Efforts to regulate chainsaw milling have been unsuccessful, leaving the subsector unaccountable more than two decades since it emerged.

He said the LRA and FDA were discussing the latter institution’s takeover of the chainsaw milling revenue but had not concluded.

“Furthermore, [the] FDA is formulating several regulations,” Sengbeh told The DayLight. “When put into effect, [the chainsaw regulations] will allow LRA to better administer taxation within the subsector.”

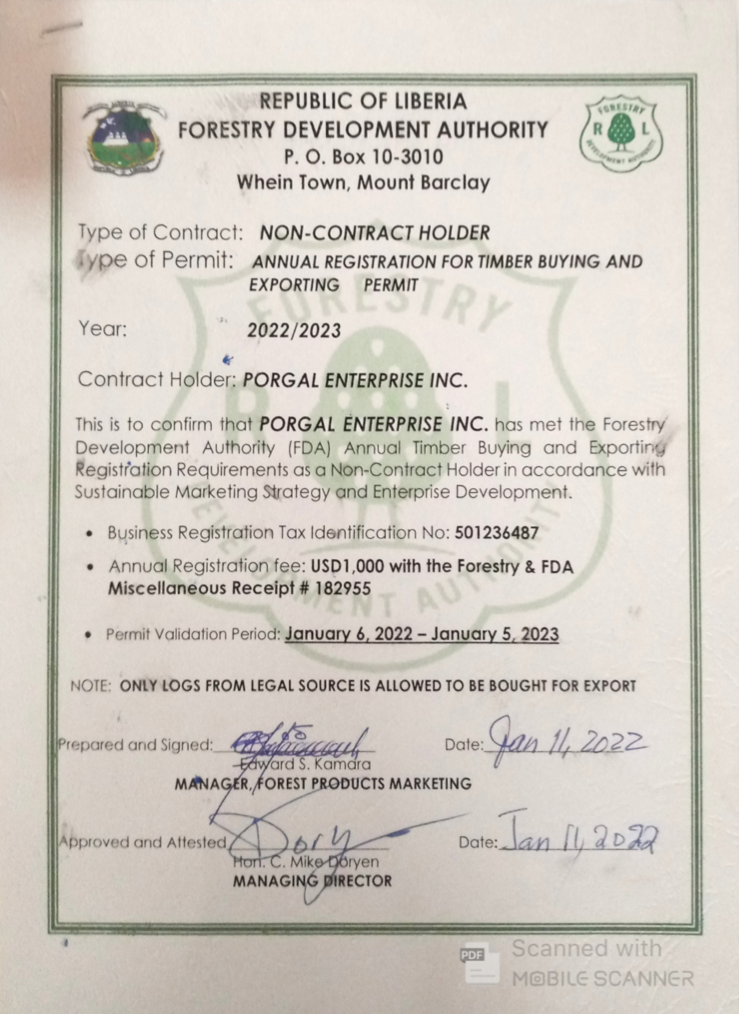

The FDA has attempted to draft a chainsaw milling regulation on three occasions but has completed none. In 2011, the agency drafted the first regulation but could not enforce it. It tried again in 2019 but got the same result. Finally, it formulated the Chainsaw Milling Regulation in 2022. However, the government has yet to gazette it, a requirement for enforcement.

Under the proposed 2022 regulation, the FDA will issue chainsaw milling permits and pay fees through a special, transparent channel.

‘In his bedroom’

Buah and other checkpoint contractors provided a likely insight into how the FDA likely misused chainsaw money in the last six years.

The DayLight had caught up with Buah after he appeared on Forest Hour on Okay FM when he and other contractors were agitating for compensation.

In the interview with The DayLight, Buah said on one Sunday morning in 2019 he reported L$50,000 in Plewon’s bedroom.

“It was the first time I was like a king sitting on a table because I [had] carried corrupt money,” Buah said. He added that “[Plewon] gave me L$10,000 and said, ‘Pay your way and go back.’” Plewon and Doryen did not respond to questions about their responses to this and other allegations in this story.

Buah said over the years, FDA checkpoints were shared among top managers of the agency. And checkpoint staff had to befriend the top managers—and, in some cases, their relatives—to be assigned and maintained at a given assignment.

Other checkpoint contractors—Benjamin Taryon of Maryland, Aaron Mulbah of Bong and Arthur Miatona of Grand Gedeh—corroborated Buah’s account.

For instance, “Managing Director [Mike Doryen] [had] checkpoints like (Klay and Ganta) under his control that [made] report to him monthly,” Taryon said. “The Deputy Managing Director [Benjamin Plewon] as well and Edward Kamara.” Edward Kamara did not reply to questions in a hard-copy letter and an email. Nearly a month after he received the communication, he emailed this reporter, asking him to instead write Merab, whom the reporter had already written.

Allegations of the FDA’s misuse of chainsaw fees first appeared in 2020. A FrontPage Africa investigation alleged that the FDA was collecting hundreds of thousands of Liberian Dollars but was not depositing the same into the government’s revenue. For instance, more than half a million Liberian Dollars was generated by Klay Checkpoint alone in Bomi for January.

The investigation also alleged that Doryen and Plewon wrangled over the checkpoint funds.

“The top hierarchy at the FDA [has] been mismanaging this money and diverting it to their personal use instead of depositing into government’s revenue account,” FrontPage quoted an anonymous source.

Doryen denied the allegation at the time. He accused the sources FrontPage Africa cited of wanting “to continue benefiting from the spoiled system.”

‘Campaign money’

Buah, Taryon, and another checkpoint contractor Aaron Mulbah said Edward Kamara invited checkpoint contractors to a meeting in Paynesville ahead of last year’s elections.

“Edward Kamara informed checkpoint staff and supervisors to work harder because the money they were about to generate was for campaign use,” Taryon said. Checkpoints were tasked in line with their monthly capabilities, Taryon and Miatona added.

“I don’t think that money was used for campaign purposes. The [managers] themselves used that money. It was just a strategy,” said Taryon, saying the money was hand-delivered, not paid via mobile money.

The checkpoint staffers were not just mere pawns in the scheme. They were involved in corruption, according to Buah. He admitted that he pocketed checkpoint fees for several years. He singlehandedly built the FDA’s sub-office in Belefanah at the cost of US$6,400, sharing pictures of the building with The DayLight.

“I had to do one or two corrupt practices [to survive],” Buah said.

In November last year, Buah appeared on Forest Hour on Okay FM, saying he was open to an audit.

“My challenge I will give the incoming government is before you take a seat in the FDA, please audit us. I am included…and the audit must start with me,” Buah said.

Buah furthered: “Please audit me to get the right things done at the FDA checkpoint.” (Merab has spoken about a payroll audit, not chainsaw milling or other areas)

As of January, the FDA owed checkpoint staff 22 months arrears, summing up to more than L$2 million (US$103,000), based on The DayLight’s calculation.

The story was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).