Top: A drone shot of a log yard in Greenville, Sinoe County. The DayLight/Derick Snyder

By Mark B. Newa

MONROVIA – Forestry violations and delayed payments of benefits to logging-affected communities were the major issues at the just-ended forest conference hosted by the Liberian government.

The “Forest and Climate Resilience Forum” was expected to reassess the commitment of the Liberian government and the international community to the protection of the country’s rainforest, the largest in the west African region.

The event came on the backdrop of reports of widespread irregularities and impunity in Liberia’s forestry sector. Associated Press recently reported that President George Weah ignored calls from foreign partners to tackle illegalities in the forestry sector.

“Current situation in Liberia`s forest sector is worrying,” said Laurent Delahousse, the head of the European Union (EU) Delegation, at the close of the event over the weekend. “It is characterized by [……] too short rotations, by the lack of proper forest management plans, and by illegal logging, which are real threats to forest regeneration and which affect the commercial and the global value of the forest,” Delahousse added.

On Thursday, the first day of the conference, more than 20 international nongovernmental organizations said the Liberian government was failing to control the illegal logging and undermining the systems in place to control it. They come from China, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, the Netherlands, Belgium and Finland.

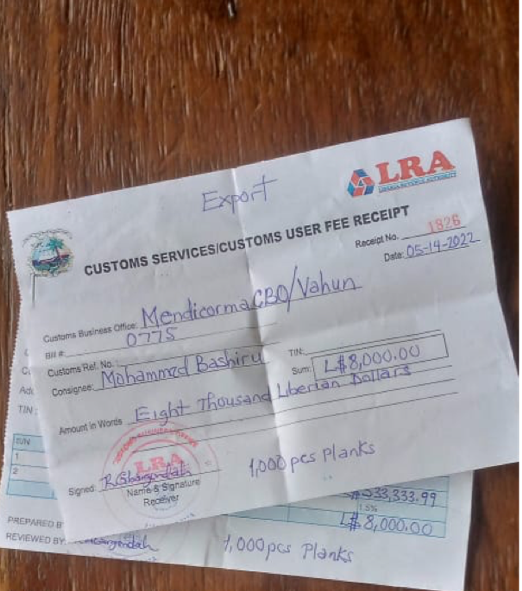

“We call on the government of Liberia to ensure all timber exports go through the LiberTrace, the traceability system, and to close down all existing routes for laundering illegally sourced timber,” the group said in a joint statement.

The Managing Director of the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) Mike Doryen brushed off criticisms, promising to grant access to public information. He blamed communities for the situation.

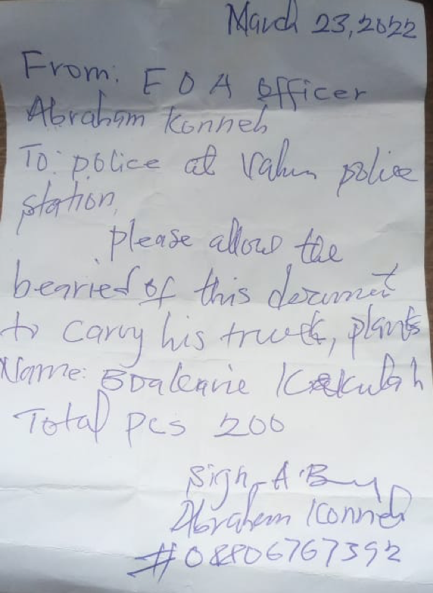

“Illegal logging activities usually begin with forest communities. These communities are undermining our efforts to deal with violations,” Doryen said.

“People go in the communities and take money from other people to harvest and transport timber to town… outside what is required law, it is illegal logging,” Doryen added. He, however, promised to set up a task force to monitor and regulate unlawful activities in the forestry sector.

Communities’ Benefits

There were a lot of concerns about communities’ benefits during the two days of the event.

By law, communities hosting large-scale logging concessions and former small-scale ones set aside exclusively for Liberians, are entitled to 30 percent of the land rental fees companies pay. But this is not the case. The government, which receives the payments, owes communities US$6.6 million.

Outside the hall at the Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Ministerial Complex, where the event took place, people from those affected communities protested. The protesters carried placards with inscriptions: “Pro-poor for the poor but not against the poor,” “Government of Liberia pays our land rental fees and the forestry law is clear on community benefits, among others.”

“This money is not forthcoming, with at least over US$6 million still outstanding. The little money that has come through was [either] late or meddled in corruption,” said Loretha Pope-Kai the chairperson of the National Civil Society Council of Liberia, the largest conglomerate of pressure groups in the country.

“Our forest communities live on the forest for their cultural, social, economic, and all other needs. Forests are therefore key to all considerations of Liberia’s… future,” Pope-Kai added, receiving huge applause.

National Benefit Sharing Trust (NBST), a watchdog that oversees communities benefits, said the delayed payment made it difficult for the group to function. It is largely funded by payments communities get. It has spent US$1.8 million on 53 projects nationwide, it reported last year.

“Funding gap is undermining the long-term sustainability of the NBST,” Kollie said.

The theme of the two-day forum was “Catalyze renewed commitments and strengthen partnerships in sustainable forest management as key strategies supporting the Government of Liberia’s Pro-Poor Agenda for Prosperity and Development (PAPD).”