Top: An Iroko Timber and Logging Company log yard outside Greenville, Sinoe County. The DayLight/Derick Snyder

By Esau J. Farr

KARQUEKPO, Sinoe County – In early 2022, there were widespread jubilations across the eight towns that own Central River-Dugbe Community Forest. They had leased the 13,193-hectare woodland to Iroko Timber and Logging Corporation for 15 years in exchange for development benefits.

But more than two years later, Iroko failed to live up to the agreement. It owes the villagers a huge debt and required projects.

“Our expectation was to bring development to our district and various towns…, including schools, clinics and safe drinking water for our people,” Alexander Slah, a member of the community leadership, said. “I am actually disappointed.”

As it stands, Iroko owes the Central River Dugbe Community US$20,368, based on interviews and official records. These fees include land rental, educational support, volunteer teachers and forest protection. Unpaid harvesting fees stand at US$8,927, according to official records.

The harvesting fees could be higher. Iroko declared 523 logs constituting 3,570.848 cubic meters, official records show. However, it abandoned some of the logs in the forest, locals say. Bartee Togba, the head of the community’s leadership, said he and other townspeople would scale the wood to determine Iroko’s full debt.

Besides unpaid fees, Iroko has failed to undertake contractual projects. It has not constructed five hand pumps it should have completed by last year, according to the contract.

“Instead of installing the hand pumps between November and March, the company started in June to August. So, the water table goes low during the dry season…,” Slah said. Arthur Nagbe, a religious leader in Karquekpo, corroborated his account.

Iroko is yet to construct three boundary roads connected to Karquekpo and a guesthouse, which should have all been completed last October. The renovation of an elementary school and the construction of a library that should have been completed this December, according to the agreement, have not also started.

‘Handpicked’

Like Iroko’s external failures, there are indications of internal disappointments since its establishment in July 2021.

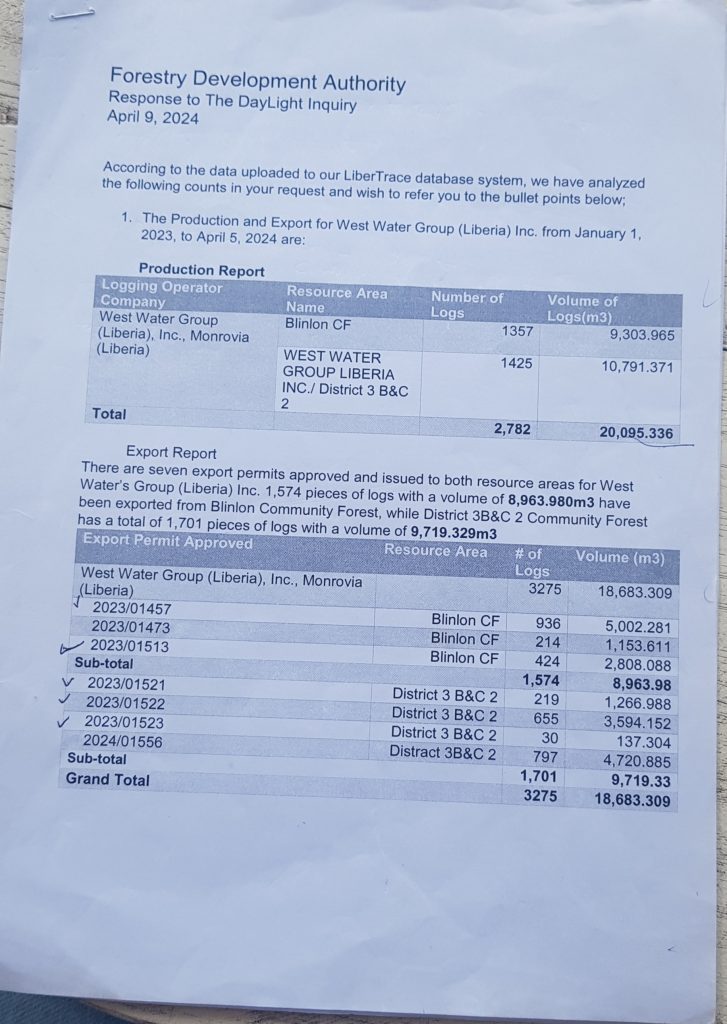

Iroko targets 100,000 hectares in 15 years but cannot even manage 13,193 hectares so far. The firm projected production of 50,000 cubic meters of logs as of this year but has produced only 3,570 cubic meters of logs since 2022, official records show.

It declared that it owned eight earthmovers and leased nine others. However, it has been seen with way fewer. One old machine is at the log yard near Greenville and two others were parked in Polay Town after Karquekpo.

Togba criticized the FDA for the Iroko situation. “They (FDA) must know that they have equipment that is up to standard but these things were not done,” he said.

But townspeople The DayLight interviewed blamed the community leadership for choosing Iroko. They said community leaders who vetted Iroko did not have the experience to do so. “They were handpicked,” said Ernest Slah, a resident, in an interview on Somalia Drive, outside Monrovia.

Togba dismisses that claim. He claims only the government has the responsibility to vet companies, though locals have that right in community forest.

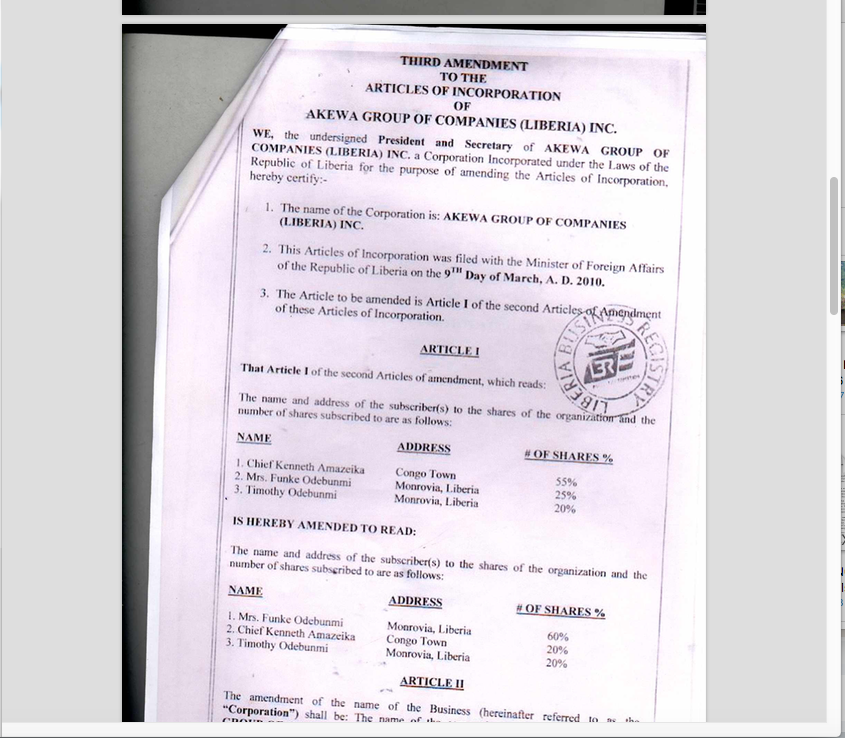

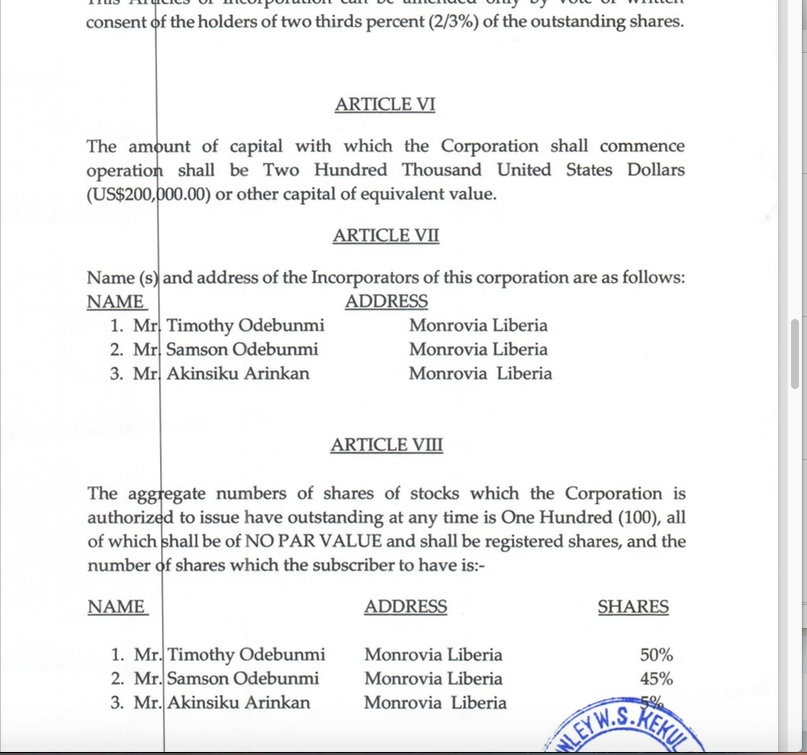

Iroko is a new company and did not have a track record at the time it signed the Central River Dugbe contract but its majority shareholder, Timothy Odebunmi, was a red flag. The Nigerian has a record of persistent, perennial indebtedness to communities through his other company, Akewa.

Akewa had owed communities hundreds of thousands of United States dollars for over a decade. One of its contracts was cancelled with unpaid fees and another has been embroiled in a lengthy debt-related out-of-court settlement.

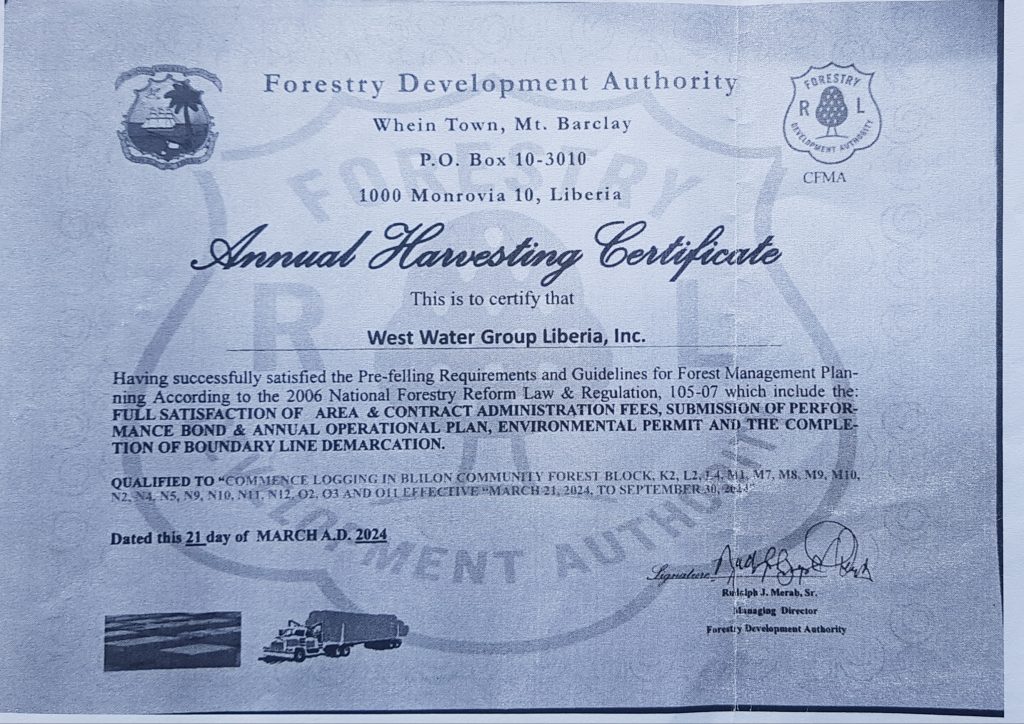

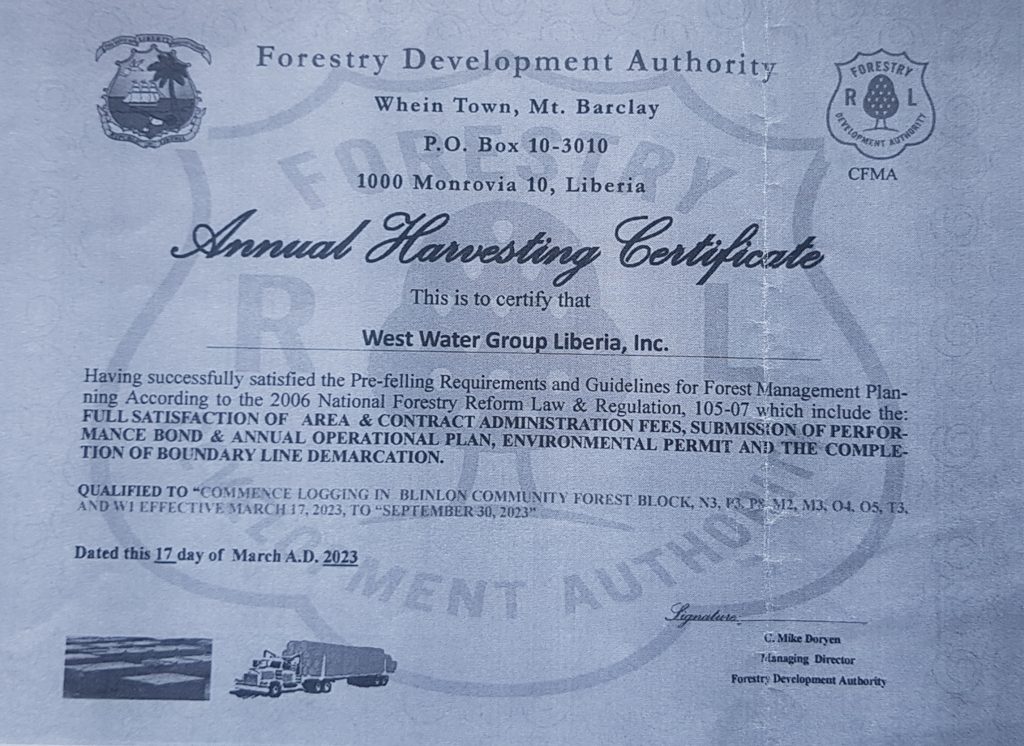

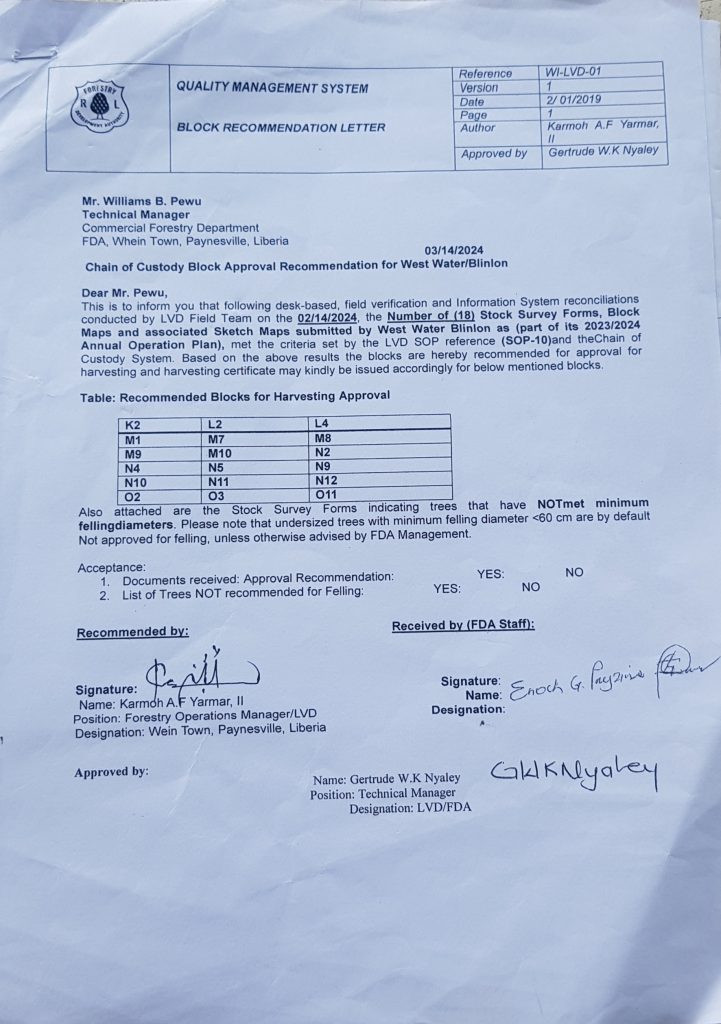

That aside, Odebunmi’s shares in Iroko disqualified the company from conducting logging activities in Liberia at the time of the Central River Dugbe contract. Odebunmi has a 20-percent stake in Akewa Group of Companies, which was fined for forgery in 2019. The FDA’s Regulation on Bidder Qualifications rules out companies whose owners are linked to public dishonesty for five years. The FDA ignored that rule and prequalified Iroko.

Lied under oath

Iroko shrugs off claims and indications of struggling to live up to its contract and denies any wrongdoing.

“We don’t know what constitutes a ‘capacity issue’ from your point of view, and can, therefore, not address your question,” Iroko said in an email.

“We would like to state that Mr. Timothy Odebunmi is not aware of having own a share in Akewa, and also Mr. Timothy [Odebunmi] has no knowledge of any tax clearance forgery issue as alleged,” it added.

Iroko’s claims are not factual. More than one year ago, The DayLight exposed Odebunmi’s connection to Akewa in which the newspaper emailed the company about its findings. Moreover, a recent review of the forestry sector lists Odebunmi as an Akewa shareholder.

Iroko might have avoided the capacity issue. However, everything about the company’s operations is suggestive of a struggle for survival.

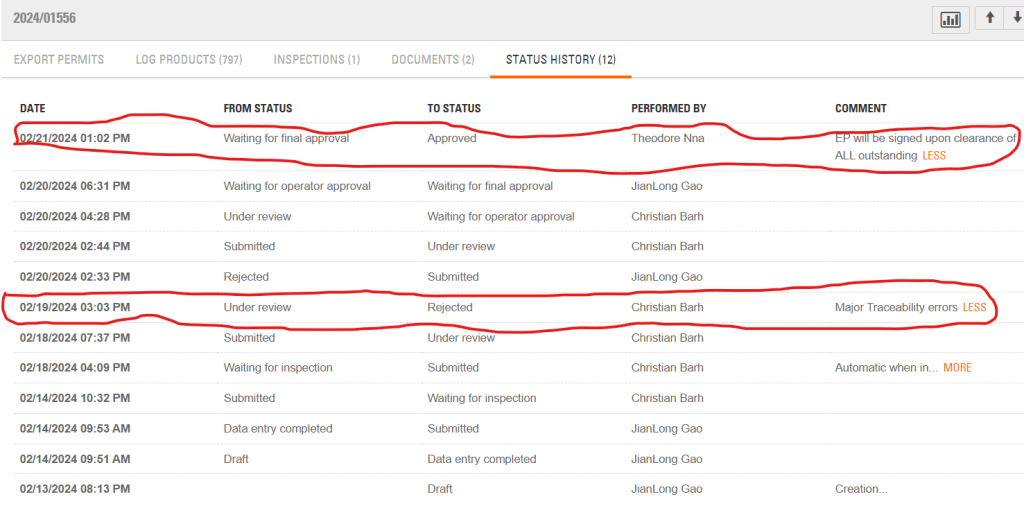

Two months ago, the FDA approved the export permit of Iroko to sell over 2,600 cubic meters but it has not exported the consignment. It has not exported any of the logs it harvested nearly two years ago. A recent DayLight investigation found the logs are abandoned, as some six months have passed since they were harvested, the longest period a log should stay anywhere before export. The FDA said it would investigate the abandoned logs accusation.

The FDA argued it approved Iroko’s contract because it had no list of debarred companies or individuals. The regulator further said it could not enforce the qualification regulation because Iroko did not bid for Central River Dugbe.

Those assertions are not backed by law. While the regulation requires the FDA to form a debarment and suspension list, it does not restrict a company or individual’s eligibility to the list. An individual’s eligibility is covered under the prequalification criteria, the standard for that person’s participation in logging activities.

The fact Iroko was prequalified with Odebunmi’s stakes shows that the company lied under oath. Per the regulation, the Nigerian firm should be prosecuted for perjury. The FDA referenced that provision when it certificated Iroko: “Any statement made under oath to the panel that is found to be false renders this certificate null and void.”

Locals are running out of patience over Iroko’s delay in meeting its contract obligations. They have planned a meeting to discuss their future with the company after the Independence Day celebrations. Some have already made up their minds.

“We are disappointed because the company failed us,” said Arthur Nagbe, a community leader. “I don’t even want to work with them again.”

This story was a production of Forest and Environmental Journalists (CoFEJ).