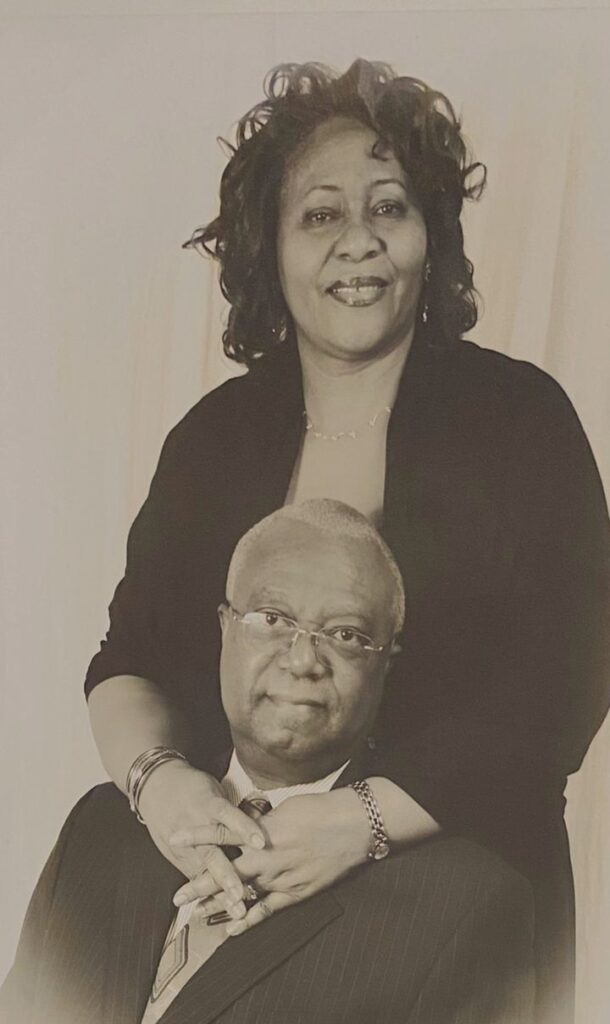

Top: Former Minister Cooper Kruah smiling in his office at the Ministry of Post and Telecommunications: Facebook/Emmanuel Fred

By Mark B. Newa

- Cllr. Cooper Kruah was a shareholder in a logging and mining company while he served as Minister of Posts and Telecommunications

- Universal Forestry Corporation (UFC) received nearly a dozen mining licenses and one logging contract while Cooper was a minister

- Kruah tried to cover up his conflict of interest by pretending to turn over his shares with an apparently fake company document

- With Kruah a shareholder, UFC was involved in an illegal subcontract, illicit logging, and smuggling of logs

- Amid evidence of Kruah’s and UFC’s offenses, both the Forestry Development Authority and the Ministry of Mines and Energy did not punish Kruah or UFC

MONROVIA – In May, President George Weah dismissed then Minister of Posts and Telecommunications Cooper Kruah after attending a Unity Party rally, ending the veteran lawyer’s four-year stint in the government.

Kruah’s departure sparked an instant controversy—betrayal versus “political intolerance.” However, he has left a host of irregularities in the logging and mining industries with impunity.

These offenses range from a conflict of interest to an unlawful extraction of minerals and timber in his hometown of Nimba County. The acts violate the Liberian Constitution, the Code of Conduct for Public Officials, the National Forestry Reform Law and the Minerals and Mining Law of 2000.

UFC was established on February 9, 1986. Edward Slangar, a former presidential advisor, holds 10 percent. Jim Kyung follows with 70 percent. Naranyan Vasnani, a foreign national, holds five percent. And Cooper Kruah the remaining five percent, according to the company’s legal documents at the Liberian Business Registry.

President Weah appointed Kruah in February 2018 and was confirmed by the Senate in August 2018. However, Kruah did not relinquish his shares or take other legal actions to avoid a conflict of interest.

UFC would go on to have more than a dozen mining licenses and a logging contract in Nimba and Grand Bassa, while Kruah served as the Postmaster General of the Republic of Liberia.

Cover-up Exposed

The DayLight initially exposed then-Minister Kruah in an investigation last year. After the publication, Kruah lied that UFC amended its article of incorporation in 2019. “This amendment of the article of incorporation is the best evidence for the public,” Kruah said in a statement at the time.

But records of the Liberia Revenue Authority (LRA) show that UFC did not amend its article of incorporation in 2019. Companies pay a fee at the LRA to amend their legal documents. UFC did not make any such payment, official records show.

This new evidence reinforces The DayLight’s previous reports.

Moreover, UFC’s so-called article of incorporation, obtained by The DayLight, physically appears to be fake. The document misspells Kruah son`s name: “Prince M. Kuah” instead of Prince M. Kruah. It also came more than one and a half years since Kruah became a government official.

Conflict of interest aside, evidence points to UFC’s violations of forestry and mining laws while Cooper Kruah was a minister.

Stealing Logs

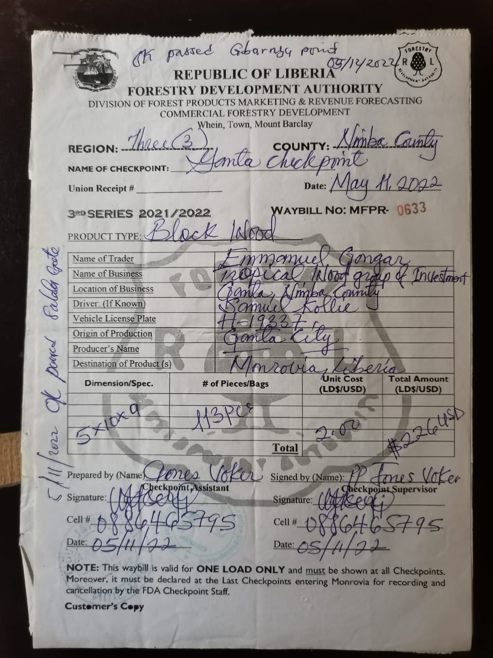

A high-profile 2021 report found UFC committed a number of offenses. The report said UFC did not declare “massive” harvesting of timber in the Sehzueplay Community Forest, felled trees outside of its contract area, and transported logs to a sawmill without valid documents. The report also found UFC did not pay the community and the government any fees for the logs.

Illegally harvesting timber violates a number of forestry legal frameworks, including Liberia’s Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA) with the European Union. No actions were taken against UFC with then Minister Cooper Kruah as one of its shareholders.

The Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (LEITI) report for 2019-2020 shows UFC skipped an environmental permit. And The DayLight reported UFC did obtain a harvesting certificate before operating, citing a ranger’s memo.

As of March 2022, UFC owed both the affected community and the government US$155,000, according to the joint implementation committee of the VPA. This is the second-highest debt owed by a logging company at the time. The FDA did not grant The DayLight’s request for UFC’s updated outstanding payment, another violation of forestry laws.

UFC subcontracted an illegitimate company without the approval of the FDA or the consent of the leadership of Sehzueplay Community Forest. The manager of Ihsaan Logging Company Mohammed Paasawe was dismissed as Superintendent of Grand Cape Mount County for corruption.

The FDA could have avoided all of this, though. It ignored the Regulation on Bidder Qualification, by prequalifying UFC to operate, while then Minister Cooper Kruah remained its shareholder.

The agency did not respond to questions for comments. However, last year, Managing Director Mike Doryen promised to investigate and take appropriate actions against UFC and Cooper Kruah but has not. “I will not protect any official of government who breaks the law,” Doryen said at the time.

Conflict of interest carries a fine between US$10,000 and US$25,000, up to three times the sum Kruah has received from his equity in UFC, or a prison term of up to 12 months, according to the National Forestry Reform Law.

UFC’s Illegal Goldmines

UFC thrived with Kruah a cabinet minister. Between 2018 and last month when he was sacked, the Ministry of Mines and Energy awarded UFC nearly a dozen mining licenses and a dealer license, according to official records. It managed only a few prior to Kruah’s appointment.

That boom is reflected in UFC’s figures. In the 2018-2019 period alone, UFC produced 16.85 kilograms of gold with export valued at US$313.525, according to the LRA payment record. It paid the government US$99,545, one of the highest contributions then, the Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (LEITI) reported.

The ministry unlawfully allowed UFC to operate, despite Kruah’s admitting to a conflict of interest, and did not penalize it amid the evidence.

The ministry declined an interview on the subject in the last 12 months. On both occasions, Minister Gesler Murry referred The DayLight to Deputy Minister Operations Emmanuel Sherman, who evaded an interview.

Like the forestry law, the Mineral and Mining Law requires officials to not hold shares in companies that actively operating. It prescribes a fine of not more than US$25,000, a prison term of up to one year, or both upon conviction in a courthouse.

Kruah declined an interview, the second time he has refused to speak on his connection with UFC. This month, he promised to grant an interview on the matter but—like last year—insisted he did not want the conversation recorded. This reporter rejected that suggestion, as it goes against The DayLight’s editorial policy.

This story was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).