Top: Masayaha’s bridge in Gbargbo, River Cess County breaks the FDA’s standards for a log bridge. The Ministry of Public Works disapproved of the construction. Picture credit: An anonymous villager

By Aaron Wesley Geezay

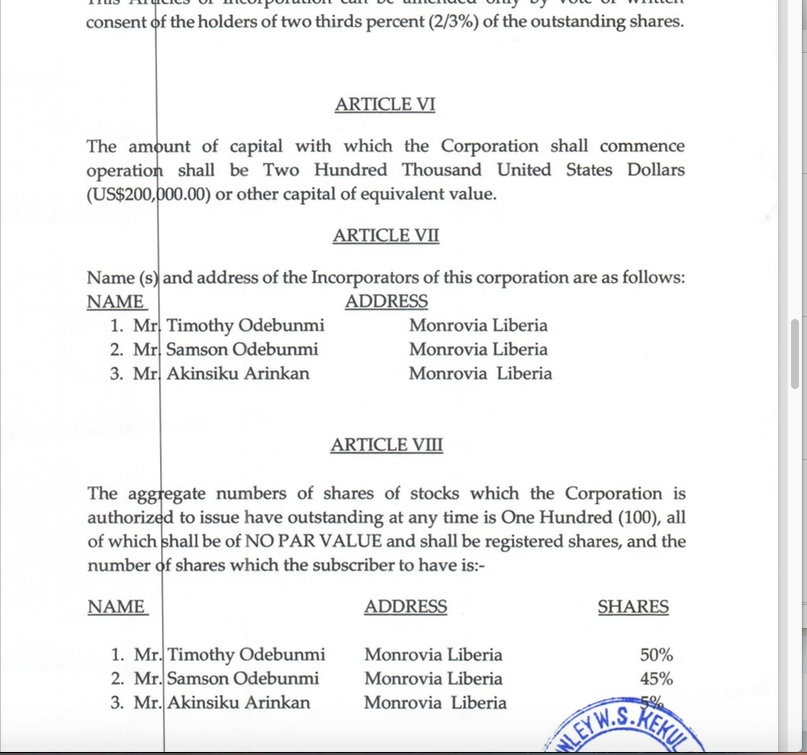

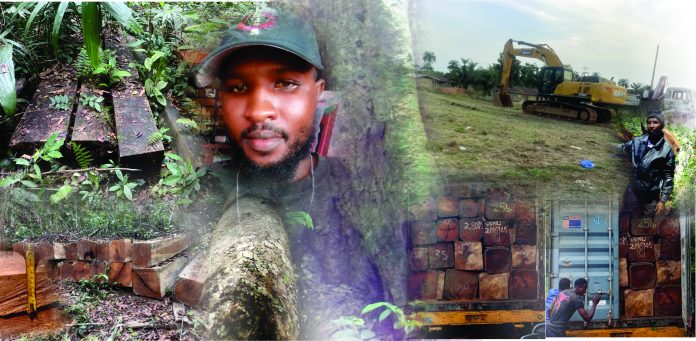

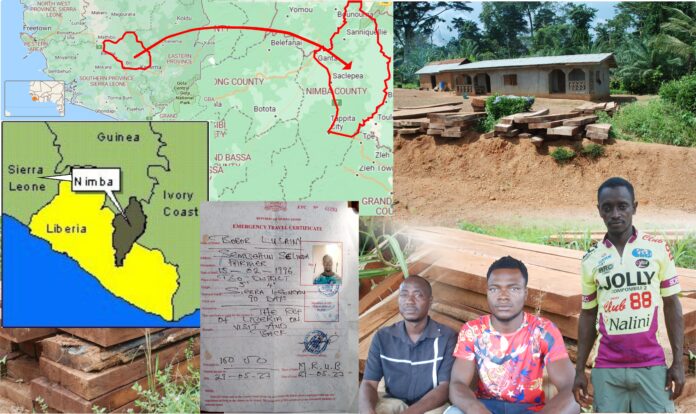

GARGBO VILLAGE, River Cess – Masayaha, a Lebanese-owned company, known for its repeated logging offenses, has harvested about 500 logs in River Cess County, outside of its area of operations.

In November 2021, Masayaha had a 15-year logging contract with the 43,792-hectare Bloquiah Community Forest in Gboe/Ploe Administrative District, Grand Gedeh County.

One year later, Masayaha entered a verbal logging deal with Gbargbo, a River Cess’ Norbor Clan village about 80 kilometers away from its contract area. Under the deal, villagers would allow the company to harvest the logs and build a temporary bridge over the Cestos River, which would later be transformed into a partial concrete structure.

The log bridge was good news for both parties.

Masayaha needed it to transport logs from Grand Gedeh to Grand Bassa since heavy vehicles were disallowed to use the Timbo River Bridge between Sinoe and River Cess.

The villagers saw the bridge as an opportunity to connect the Norbor Clan in the Yarnee District to the Kploh Chiefdom in the Central River Cess Administrative District.

“They asked us to allow them to cut 250 pieces of logs to fix the bridge,” Samuel Gbargbo, a resident of Gbargbo Village, told The DayLight. “And because we have been suffering for the road we agreed.”

‘The people… fooled us’

Per the agreement, Masayaha paid the community US$1,500 and began harvesting. However, the logs were insufficient to complete the bridge so the parties signed another verbal agreement. This time, Masayaha only paid US$700, with the remaining US$800 yet to be paid, our investigation found.

And there were other problems. There was no concrete component of the bridge as Masayaha had promised. The bridge had been completed over a year ago, yet the company had failed to construct any concrete pillars. Besides, it abandoned several logs that they felled in Gbargbo’s forest.

This and the debt issue angered the villagers, who threatened to protest.

“The people came and fooled us and made us work for nothing,” said Melvin Wolloh, town chief of Norbor Clan.

Ali Harkous, Masayaha’s CEO and owner, said the Forestry Development Authority permitted it. “We applied to FDA to permit us to get the logs from around the area and they approved and we also approached community and they agreed,” Harkous said. He refused to share a copy with The DayLight or allow this reporter to see it.

Harkous would not speak to the villagers’ claim but budged after persistent inquiry. “Frankly, tell them they should not worry, we are going to give [them] their money.

“We invested all we have and credited from some financial institutions. We are really into [a] financial problem,” Harkous said.

Harkous was right. The FDA permitted Masayaha to harvest logs for the bridge. However, his company grossly violated the permit’s terms.

The document and other papers, the FDA provided, did not permit Masayaha to harvest logs in River Cess, but rather Sinoe County. Two letters written by then-Senator Milton Teahjay of Sinoe County and Bloquiah Community Forest, seen by The DayLight, mentioned the Tarjuwon District.

Also, the permit ordered Masayaha to work with the FDA staff in that area to identify targeted trees and calculate the volume logs for the project. That, too, did not happen.

FDA’s record of the Masayaha felling in Gbargbo Village shows that the company felled 200 trees, not 500 the villagers said.

Then of the 200 logs, 62 were untagged, according to the FDA record. Similarly, the logs on the bridge, on an open field on the riverbank and in the bushes were untagged. Even the tree stumps this reporter photographed were missing obligatory tags.

This is a violation of the Regulation on Establishing a Chain of Custody System. In forestry, every log must be marked, tagged and entered into the system to ensure its legality. It is crucial to Liberia’s timber-trade agreement with the European Union.

The dates on the harvesting record and the communications are inconsistent, further proof of a dishonest operation. It shows rangers identified targeted trees on November 29, 2022—William V.S. Tubman’s birthday—for the harvesting. However, Masayaha’s request and the FDA’s response were written in December and January, respectively. This reveals that rangers had already counted, and tagged some of the trees before the FDA approved the harvesting.

Roadside logging

It is not the first time Masayaha has harvested logs outside its contract area. In 2022, a DayLight investigation exposed Masayaha’s illegal logging activities outside the Worr Community Forest in Grand Bassa County, where it exploited villagers’ need for roads. The report cited an August 2021 FDA publication in which investigators found evidence Masayaha connived with locals to steal timber. No actions were taken against the company for those activities, despite a protest.

William Pewu, FDA’s technical manager for commercial forestry, said Masayaha would go scot-free for its Gbargbo Village activities. Pewu claims the FDA does not record the logs in LiberTrace, a computer system that verifies the legality of timber.

“No, those logs are not for sale,” Pewu told The DayLight in an interview last week. “You only enroll logs in LiberTrace when they are for export. Those logs are for [a] bridge construction.”

Pewu’s comments are not backed by facts. The phrase “chain of custody” covers everything from “transport, interim storage, processing, distribution, and export.” In short, it extends from a log’s “source of origin in the forest to [its] end use.”

Furthermore, roadside logging does not derive from any law or regulation. In fact, in 2009, the FDA even fined a company for harvesting a hundred logs along a path outside a concession in Grand Bassa, according to a United Nations report. A 2017 regulation imposes a fine of twice the value of logs harvested outside a contract, a six-month prison term, or both fine and imprisonment upon a conviction. Other penalties include forfeiture of harvesting rights or a logging contract.

Masayaha’s illegal operation in Gbargbo bears a remarkable resemblance to the one conducted by a company nearly a decade ago. In 2016, an investigation by the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI) found that Liberia Hardwood Company (LHC) harvested many logs outside the Bloquiah Community Forest. Strangely, some of the logs were felled in the very Gbargbo Village.

The FDA admitted at the time that roadside logging was illegal but said the logging would continue while it addressed “gaps” in the regulation. It took no action against LHC, which denied any wrongdoing, and there is still no regulation for roadside logging.

‘Not possible’

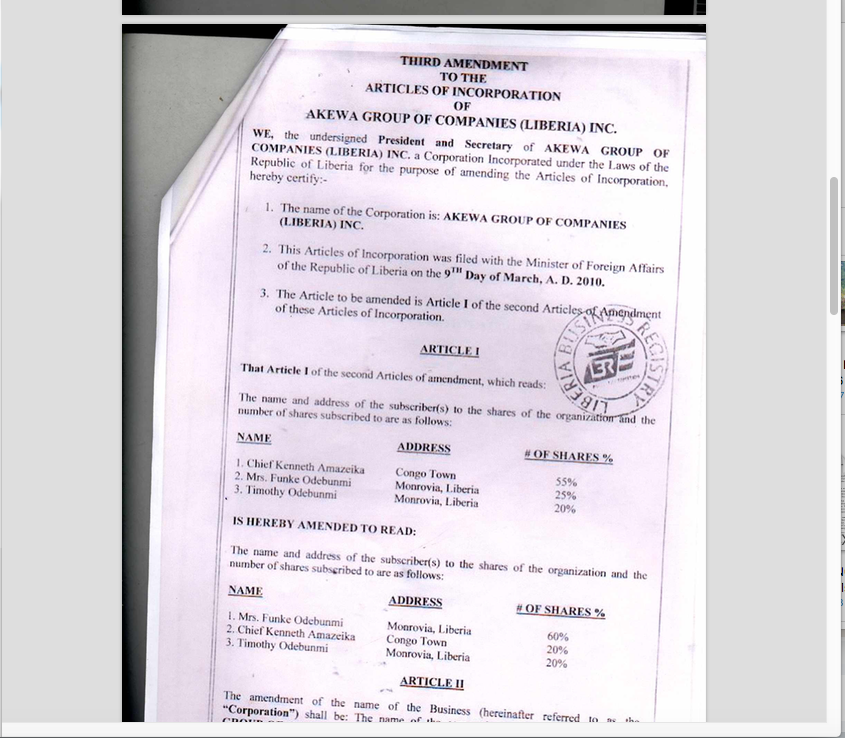

The bridge built from the illegal logs is equally tainted. It violates the standards for bridge construction, per the Code of Harvesting Practices. The code requires a log bridge to be built on a high portion of a riverbank so as not to stop or interfere with the water’s flow.

Masayaha engineers placed the logs directly in the water, stalling its natural course, photographs of the construction show.

Ministry of Public Works did not authorize the construction, a contravention of the precondition the FDA set for the construction. The Ministry said it had disapproved of the construction.

“Approval/consent was not provided on the basis that the [width] of the Cestos River was [wider],” Minister Roland Layfette Giddings told The DayLight. By the ministry’s standard, it was not possible to construct a log bridge at the location under consideration.”

That violation has led to consequences. At the start of the rainy season, the Cestos River overflowed its banks, washing many logs away. Masayaha later repaired it. Masayaha has started to use the bridge to transport logs to Buchanan.

But Fishermen, who have fished on the river for generations, now have to lift their canoes over the controversial bridge to access the other side of the river.

The story was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).