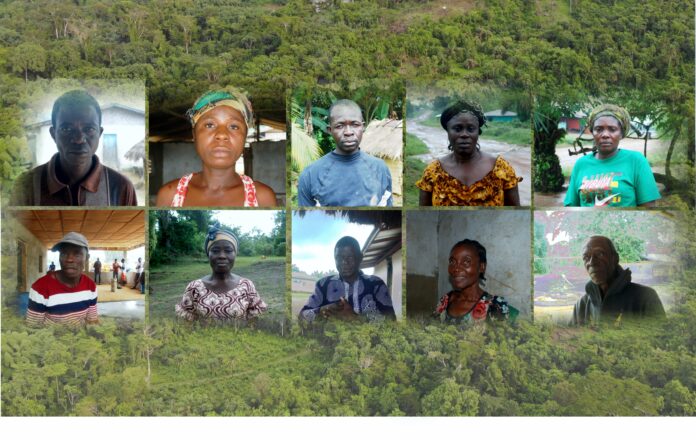

Top: Blue Carbon of the United Arab Emirates, which hosts the ongoing Climate Summit in Dubai, wants over 1 million hectares of Liberia’s rainforests. The DayLight/Jaames Harding Giahyue

By Gio Ferrarius special for The DayLight

From 30 November, the COP28 climate conference will be held in Dubai. The host country the United Arab Emirates has taken an advance on several massive carbon credit contracts in the run-up to the event.

Negotiations are underway in five countries (Liberia, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Kenya) to generate carbon credits from a total of 25 million hectares of forest (mostly tropical rainforest) that are expected to bring in billions of dollars.

That sounds spectacular, but who benefits from it? Is it the Africans, the Arabs, or is it nature?

The UAE is promising an investment of $50 billion to make the plans come through, and that could do the job, you would think.

In July of this year, a first contract was submitted for approval in Liberia, covering 1.1 million hectares of tropical rainforest. However, after protests from quite a few NGOs, the project was put on hold. What is the problem?

Well ahead of the contract, in March 2023, the Liberian government already signed a memorandum of understanding with Blue Carbon LLC, a company led by Sheikh Ahmed Dalmook al Maktoum, a member of the royal family of the United Arab Emirates. The Sheikh also runs the family holding company, which manages several businesses, particularly in energy, oil and gas and infrastructure.

It is no secret that the UAE is one of the largest oil traders in the world. So, there is plenty of opportunity for offsetting emission gasses against carbon credits. The economic importance is obvious, but simultaneously greenwashing is lurking, according to climate campaigners.

At first glance, a no-brainer for Liberia and the other African countries. The rich UAE, pumping billions into the economies of these poverty-stricken countries through carbon credits to help kickstart economic activity through infrastructure and employment projects.

But there are many things wrong with the contract that was submitted to the Liberian government. There are problems with the process that has been followed, the organizational context and the terms of the contract.

A fugitive Tuscan diplomat

The Liberian government decided to do business directly with the company, and not involve the communities in the negotiations. This was done on the initiative of the Italian telecommunications entrepreneur Samuele Landi, who is a member of the board of Blue Carbon and also the general counsul for the UAE in Liberia.

Before leaving for Dubai in 2008, Landi was CEO and major shareholder of an Italian telecom company Eutelia, a merger company of PlugIt, which he founded in the late 1990s, and mainly focused on “value-added telecom services” (erotics, horoscopes, weather reports).

Eutelia had big plans, and acquired the heavily loss-making Italian branch of the Dutch Getronics, as well as the Bull branch on the peninsula, only to succumb to its expansionism.

In that process, Landi, with his management board and some family members, embezzled tens of millions, according to a verdict against him in 2020. The accusations comprised Landi’s involvement with Liberia, which goes back to that very same period when he diverted assets to the amount of 8.4 million euros to NETCOM Liberia, in which Eutelia held a 36.5% stake. The amount was written off in Eutelia’s books but never repaid. Netcom was a Liberian startup, of which the valuation was questioned by Eutelia’s auditors, court records show.

Landi was sentenced to nine years in prison and has been a fugitive in Italy ever since. He lives and works in Dubai, where, at the time of the demise of Eutelia, he was busy with a tender for a substantial telecom contract in Qatar.

Landi did not respond to queries for comments, but in an interview with Climate Home News, he said he had referred the case to the European Court of Human Rights, claiming it was an unfair trial.

Contempt for the original inhabitants

Liberia has only one large city, the capital Monrovia, with almost 700 thousand inhabitants (including the surrounding urbanizations of about a million). After that, there are twelve cities with between ten and fifty thousand inhabitants: another 300 thousand inhabitants. The rest (almost five million Liberians) live in thousands of hamlets and villages spread over – mainly – rainforest in the 15 counties. The local population (outside the cities) lives mainly on what nature offers them, apart from some modest commercial activity.

There is hardly any infrastructure and few paved roads. Traveling is a real challenge, especially in the hinterland. Furthermore, no, or inadequate electricity supply, and a lousy telecommunications network.

The fragmented topography of the country translates into equally fragmented land ownership. The lion’s share of the territory is owned by local communities. So, Blue Carbon will have to deal with the leadership of these communities, because the landowners are the rightsholder in this kind of contract.

Apart from this, there’s a lot to say about the contract proposed to Liberia and the process that was followed. Following two consecutive civil wars, fueled by the marginalization of rural people, mismanagement and corruption, Liberia adopted several laws to protect the nation in the future.

Most of those laws were passed under the rule of Nobel Peace Prize winner President Sirleaf, in the period from 2006 onwards. An important provision throughout these new rules is that projects of a certain size must be put out to tender in competition. Another rule is that concessions for the use of territories can only be granted with the express consent of the indigenous population affected, who are in most cases local communities.

In February 2023 – in defiance of these rules – a letter of intent was signed, and in July, the Liberian government of president and football legend George Weah and the company of the Royals in Dubai attempted to rush the agreement through parliament. And all this without any form of consultation with the landowners.

A project without a plan

This makes the proposed agreements at least illegitimate, and probably illegal. And that’s not all. The purpose of this type of contract is that the local population explicitly benefits from it and is also compensated in some way for the loss of income – and other opportunities to provide for their own livelihood. Sadly, not one single concrete action is stipulated in the contract. Not for the construction of infrastructure, a road network, schools, hospitals, clean water and electricity supply, and a communication network. None of that.

There is also no provision for the creation of local employment through small-scale business or industry, ecologically responsible agriculture, or sustainable forest exploitation. Nothing at all is specified.

And it doesn’t end. The size of the investment that the Arabs will make is not determined in the contract. Billions? Yes, but how much, and who manages it?

In the few words that the contract devotes to the organization of the operation, it becomes clear that it’s really a bit of pleasantness between the Liberian state and the company from Dubai. In the end, the local population, who own the land, have no say in how the money is spent.

A one-sided contract

Moreover, the Arabs have generously favored themselves in determining the distribution key for the income from Carbon Credits. No less than seventy percent of the proceeds disappear to the Sheikh and his companions. The Liberians have to do with thirty percent, and in the end, no more than twelve percent ends up with the local population. A very unusual construction.

In the voluntary market, it is normal for the proceeds to go predominantly to the landowner. They must submit a proper plan to a certifying organization in advance, and the most important elements in this are project descriptions for nature conservation and area development that benefit the local population.

The landowner usually pays a commission percentage to an intermediary (10 percent is a normal number), who sells the harvested carbon credits into the market. Next to that, the owner often subcontracts a technical advisor/contractor for the execution of the project.

Not so with the Arabs, everything is in one hand, the hand of the Sheikh.

And what if the results of the project turn out disappointing? Well, there’s no consequence. There is no control mechanism built in, except for annual accounts that have to be submitted, and if the Liberians were dissatisfied at all, they would still be stuck with the Arabs for at least 10 years.

In short, Liberia is handing over the future development of its hinterland entirely to the United Arab Emirates and does not impose any conditions. Should Blue Carbon fail, the Liberians will have nothing to fall back on. Not an inconceivable scenario, since the company does not clarify what expertise it brings to the table, or what exactly it will deliver.

Meanwhile, the money warehouse in Dubai is flowing over, while nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie are enjoying themselves in their new hobby land.

Petrodollars for the rainforest

And now a new phase. Liberia is targeting carbon credits. Actually, the deal was already done. 50 billion for poverty-stricken countries in Africa. Good thing there were critical readers…

At COP28, the upcoming contracts will nevertheless be loudly applauded.

Uncle Scrooge has sketched a fantastic prospect, an unprecedented heap of money, which unfortunately largely flows directly back to himself.

And that in exchange for the autonomy of the Liberians who completely relinquish the perspective of their rural areas. Admittedly, carbon-deals might contribute to mitigating CO2 emissions, and potentially simultaneously benefit poorer countries.

This mechanism obviously only works under the provision of fairness and transparency. This deal brings nothing to the Liberians, and its contribution to climate and nature is dubious, to say the least.