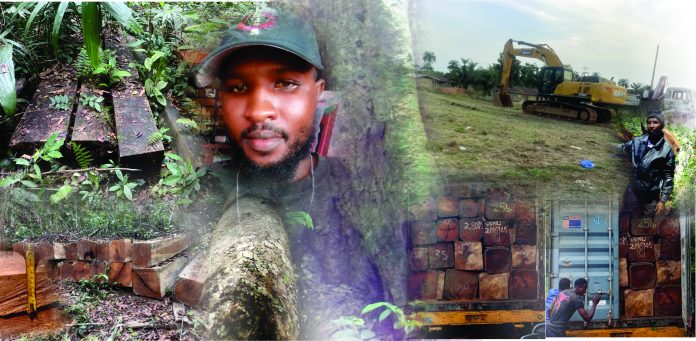

Top: A poster showing the illegal logging activities by Michael Feika in Totoquelleh, Gbarpolu County. The DayLight/Rebazar Forte

By James Harding Giahyue

TOTOQUELLEH, Gbarpolu County – “If [it is a] container, I give you my price. You buy it from me in the bush,” Michael Feika, an illegal logger, told his new client.

Feika is a broker of kpokolo, squared, compact timber whose trade the government “banned” just over a year ago but has reemerged, with authorities yet to act.

Feika shared several of his past and present operations with Joemue Wortee when they met in Paynesville on March 8. The pictures were equally revealing as Feika’s verbal pitch to Wortee, the assumed client.

“I will bring [the kpokolo] to town. It is only left with you to pay me because I got the document,” Feika said as he tried to convince Wortee of a deal.

“This thing [is] my business from day one.”

In his late 30s and with a Sierra Leonean accent, Feika sent Wortee to his network in Totoquelleh in the Bopolu District of Gbarpolu County. There, Wortee saw Feika’s setup—production sites, an earthmover, timber and a gang of chainsaw millers and haulers.

But Wortee was no businessman. He was an undercover reporter whose mission was to uncover Feika’s illegal logging activities. The reporter’s mission set off as evidence of fresh kpokolo activities began in the western countryside.

The DayLight used undercover techniques because it appeared impossible that Feika would submit to an open probe, particularly after our previous report on the return of kpokolo. Also, such investigation in a forest best guaranteed the reporter’s safety.

‘Mikelo’

The DayLight’s undercover reporter under his assumed name traveled to Totoquelleh, some 62 miles north of Monrovia.

When the reporter arrived at the destination, Feika had already informed a member of his network about the assumed businessman’s mission. The undercover reporter did not know this so, he went asking the townspeople for the teenage member named only as Morris.

Just as Feika had said, everyone the reporter asked in Totoquelleh said they knew Feika and his operations. The people call him Mikelo, a play on the words “Michael” and “Kpokolo.”

Feika and Morris live in a mud hut from where the former serves as the ringleader for their wood trafficking network of over 20 operators. At times he hosts Sierra Leonean illegal loggers for months in Totoquelleh. Feika claims that he hails from Margibi County but his Facebook account lists Freetown as his home city. Other Feikas listed as his friends on Facebook also come from Sierra Leone. This means Feika is not even qualified to conduct small-scale logging activities in Liberia, set aside for only Liberians.

The undercover reporter went to Feika’s house in search of Morris. That search took him to the home of Abadulai Fofana, another kpokolo producer in the forest-enveloped community. It was here the reporter met Morris.

The short, black teenager, who is also a motorcycle taxi driver, then took the undercover reporter on a guided tour of Feika’s kpokolo world.

As they took a footpath leading to a farm, Morris told the undercover reporter that they produced a lot of kpokolo in 2022. Their production has slowed down in the last two years and they only produce when a customer approaches them.

As they walked deeper, the undercover reporter saw some abandoned kpokolo on the floor of the dried, dim wooded area. Morris disclosed that it was one of the many locations where Feika worked.

Morris’ comments corroborated Feika’s account and that of the picture he shared with the reporter in Paynesville. Feika had said that he harvested the wood in 2022 but backed off after the supposed ban.

Feika’s new worksites in the pictures were too far for the reporter to venture even for a client. The reporter and Morris decided to head back to the town.

Nevertheless, the pictures already took the undercover reporter to Feika’s new locations. They show piles of kpokolo in the forest, felled logs waiting to be milled, targeted trees for harvesting and timber at a portable sawmill. One particular picture showed Feika posing for a picture next to another felled tree.

“The ones standing there, I [cut] one down before I could come to Monrovia,” Feika said back in Paynesville, referring to a gigantic tree. “This one is Iroko the white one,” he added, citing a first-class tree species scientifically known as Milicia excelsa, which kpokolo traffickers prefer.

‘It is easy’

About a 10-minute into their journey back to Totoquelleh, the reporter and Morris saw a score of 12-inch kpokolo that Fofana, Feika’s competitor, harvested.

Not far, lay five others in the middle of a dirt road close to the K.J. Village. The kpokolo appeared to have fallen off the vehicle transferring them from the forest. Tire impressions show clearly in the sunbaked mud.

Fofana had disclosed he kept more kpokolo in their conversation before the undercover reporter met Morris.

“The sizes are 50X50, 40X40 and 30X30,” Fofana said at the time. He meant the timber’s dimensions range from 30 to 50 inches in thickness, up to 25 times the authorized size.

“It was produced last month,” Fofana added.

“When somebody [has a] contract for me, I can do it. That business is a contract. It can come and we discuss it before we do it.” Fofana’s comments had confirmed Feika’s suspicion that other kpokolo operators in Totoquelleh would try to snatch the assumed businessman.

Upon his return to Totoquelleh from his Morris-guided tour, the undercover reporter photographed an excavator parked near a truck in an open field.

“You see that car over there,” Fofana said, pointing to the excavator. “It is the one that can hook [the kpokolo and put them in the container].”

‘Not small money’

Thankfully, the pictures Feika shared with the undercover reporter show the entire container-packaging process. Several pictures show the wood being measured with a tape rule. One shows a crane shoving kpokolo into a container, while another reveals two men sealing it up.

“Some of the containers allow eight, 14, 16 and 20 pieces of wood to go in, depending on the sizes of the wood,” Feika said back in Paynesville. He revealed the kpokolo measuring three inches and four-and-a-half inches were the ones now in demand.

Feika said he had stopped producing larger kpokolo due to the ban but was open to cutting them once he got the right offer. “If you want [them]…, it is not small money you will spend,” he said.

The prices for a container filled with kpokolo are based on the class of the wood. Prices range from US$7,000 to US$12,000, including transportation to Monrovia, according to Feika. Feika’s favorite first-class species apart from Iroko are Afzelia (Afzelia spp), Ekki (Lophira alata), Lovoa (Lovoa trichilioides) and Niangon ( Heritiera utilis). These species are expensive and produce hardwood used for shipbuilding, railroad ties and outdoor construction.

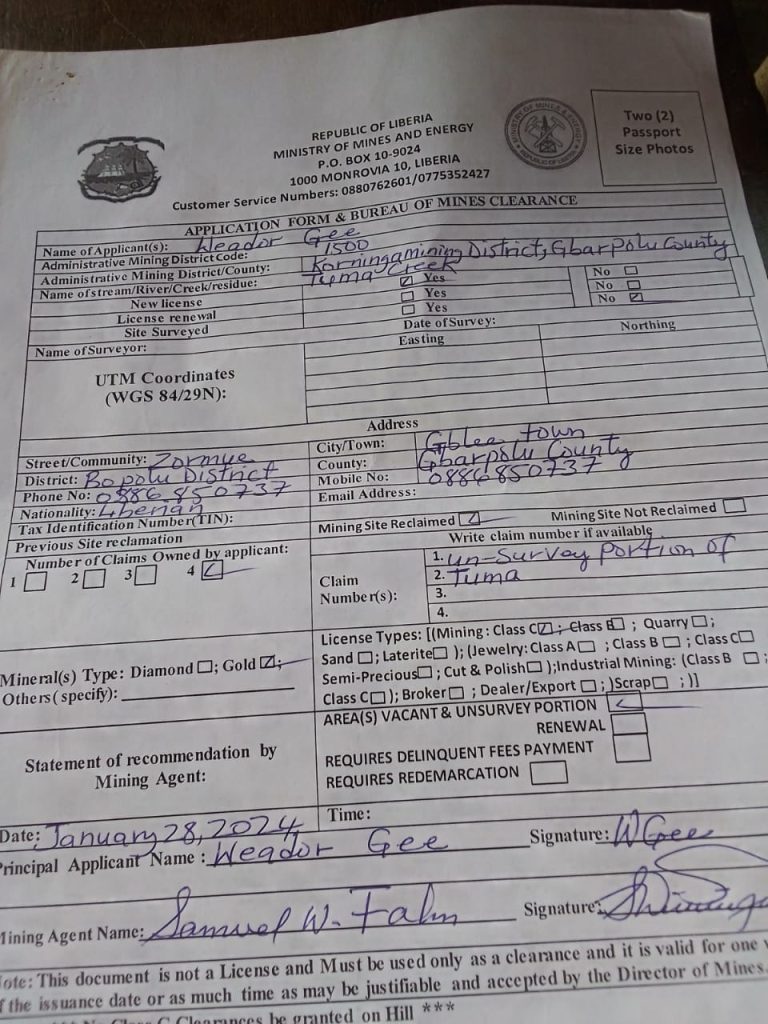

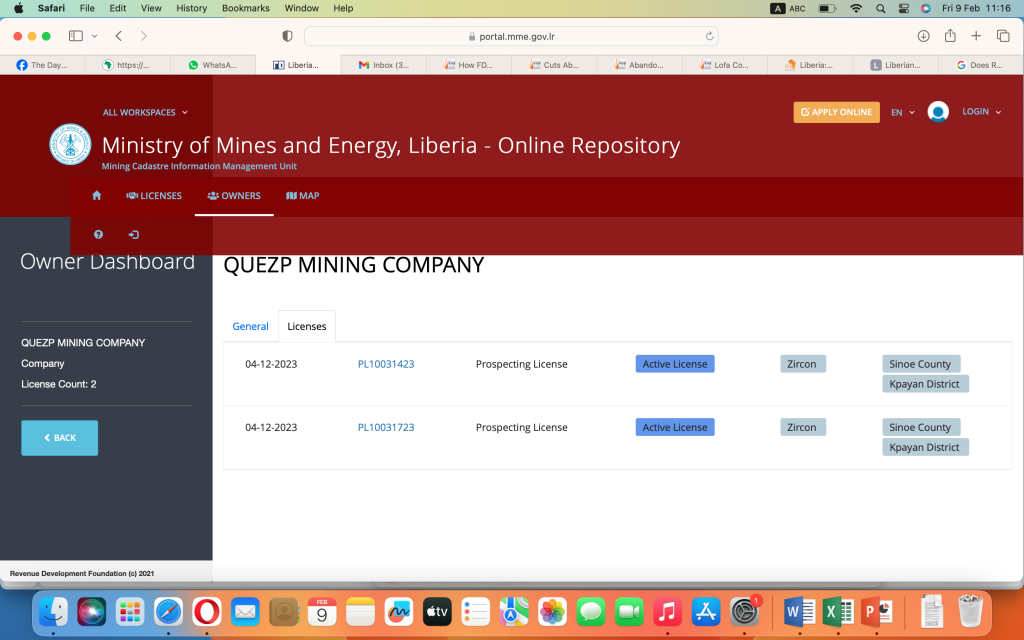

If a client wants just one container, they must pay Feika at least half of their negotiated amount. If the client wants multiple containers, they pay for at least one container upfront. However, the client must pay the FDA US1,200 for an annual export permit, US$1,000 for the paper and the balance for paperwork, Feika said. Those figures are the same as the ones on the kpokolo permit the FDA issued before the so-called ban.

Once the container is filled and sealed, Feika makes phone calls to FDA rangers posted on the Bopolu-Monrovia highway via Klay. Feika would not share the rangers’ contact or say their names.

“When I reach the checkpoint, I will say, ‘Yes, I am the one [who has] the wood. Everybody knows me because I have a document from the FDA with a license number assigned to me. I will give them my container serial number and they check it and we pass.”

But Feika warned against double-crossing him to deal with rangers directly. He recounted the story of two Korean illegal loggers, the police commander and other accomplices who were arrested in Klay, Bomi County.

“If the [authorities arrest] you, you are finished because some FDA [agents] will tell you, ‘Come, I will carry [them] for you.’ If you depend on them, you will lose,” Feika said.

Ironically, Feika did not know he was speaking to a reporter of the newspaper that exposed the syndicate. The DayLight would go on to assist a police investigation that led to the men’s arrest and the dismissal of the police commander and an FDA ranger.

Feika’s contacts and influence do not extend to the Freeport of Monrovia but he offered some valuable information. Smugglers must acquire an export permit and find a customs broker at the Freeport of Monrovia to help export the timber. It costs US$1,200 to obtain the export permit certificate from the FDA—US$1,000 for the permit and the balance to secure the document.

Once they obtain the permit, they will have to pay the container’s owner US$200 per container and US$100 for each truck to transport them.

“Forget the shipment of the wood,” Feika reassured. “Once you get money, it is easy.”

His disclosure was not news to the undercover reporter. After all, The DayLight has published illegal permits, receipts and claims by kpokolo exporters in previous investigations. Those publications also revealed the mode of the illegal trade and its ringleaders.

Faika advised his presumed client to ship the wood to Turkey or Germany. “If it is Germany, I will be happy,” he said, “because I have some of my friends in Germany.”

This was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ). Funding for the story was provided by the Kyeema Foundation and Palladium.