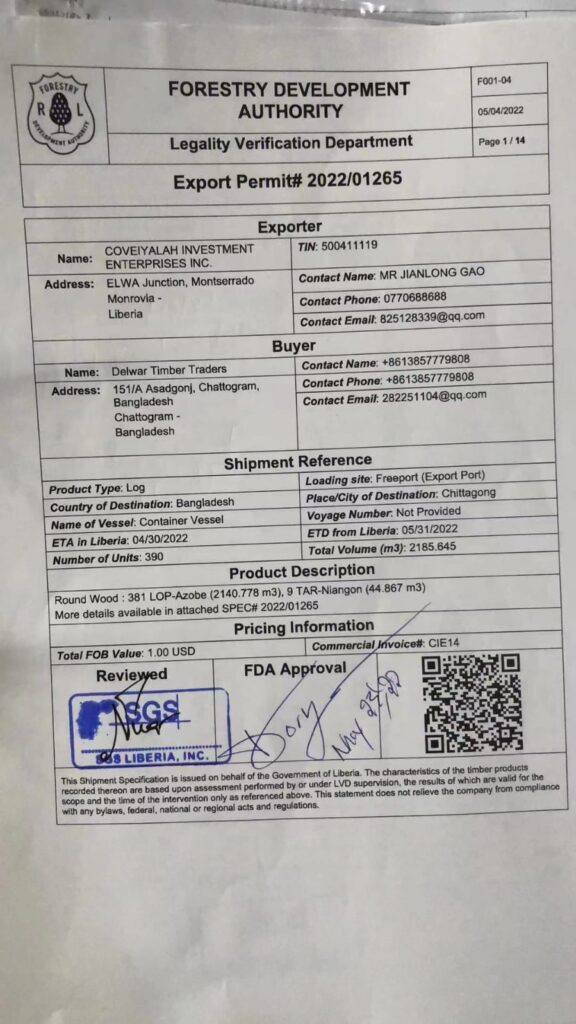

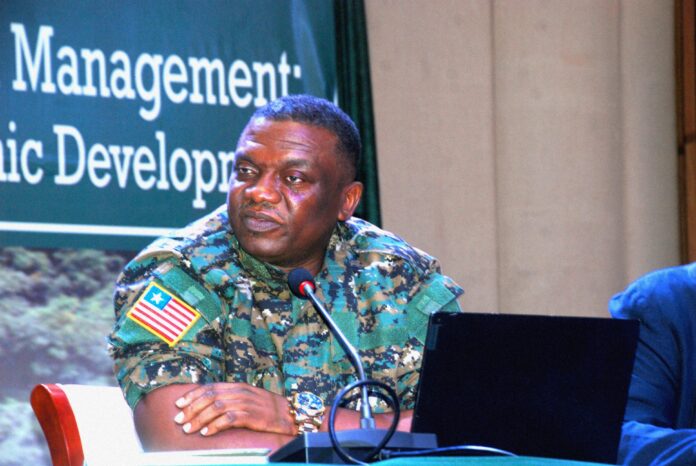

Top: The Managing Director of the Forestry Development Authority, Rudolph Merab. The DayLight/Harry Browne

By Varney Kamara and Esau Farr

SEEKON-PELLOKON – The Managing Director of the Forestry Development Authority (FDA), Rudolph Merab, is allegedly pushing a community forest to sign a logging contract with a dormant company owned by his friend.

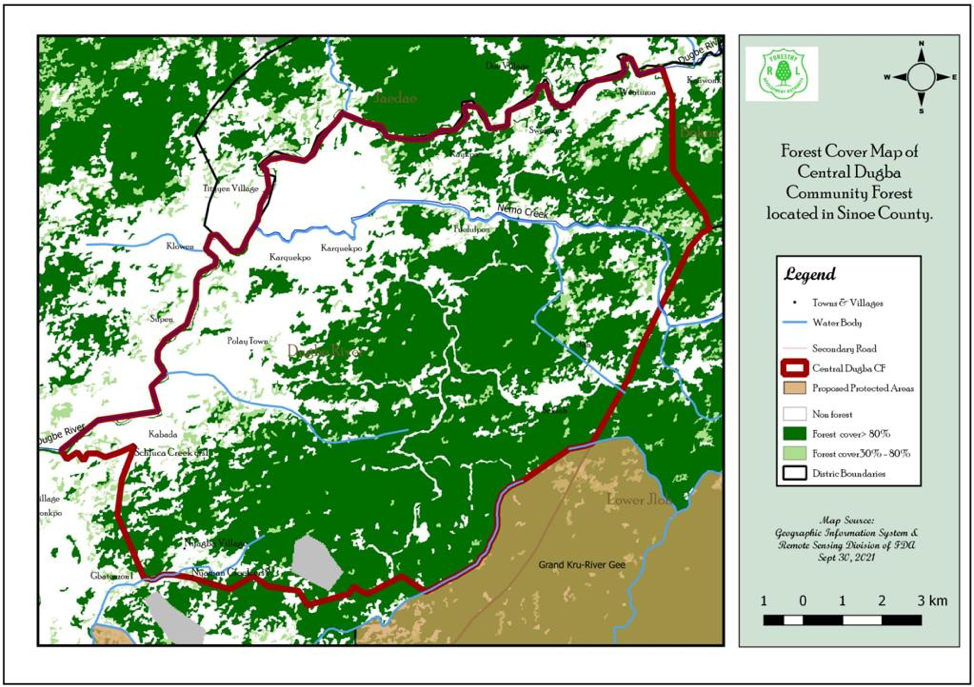

Leaders of the Seekon Pellokon Community Forest in Sinoe’s Seekon District said the FDA was on their backs to enter a contract with the Liberia Hardwood Corporation. The company is now scouting the 44,989-hectare forest, with the parties reportedly close to a deal.

“When they finish looking in the bush, we will all come back to the table to discuss the contract,” Junior Kumah, a Seekon Pellokon leader, told The DayLight.

“Our interest is to take our people from years of poverty. They need development, roads, schools, and clinics.”

Earlier this year, the FDA disapproved a deal between Seekon Pellokon and Universe Forest Group, a new logging company, because it lacked the capacity to operate two contracts simultaneously. Universe Forest has a contract with the Tarsue Community Forest in the Sanquin District.

Instead, locals said, the FDA welcomed a deal with the Liberia Hardwood Corporation, co-owned and run by Jihad Akkari. He holds 15 percent of the company’s share, while Khalil Zein Baalbaki and Giuliano Dassi hold 42.5 percent shares apiece.

Akkari’s relationship with Merab dates back to the 1990s, when both men operated logging companies. Akkari served as the vice president when Merab was president of the Liberia Timber Association (LibTA) for nearly 20 years. Multiple sources said their friendship was playing out for Akkari in Seekon Pellokon.

“FDA is the one that is negotiating,” said Kumah in a phone interview. “The FDA has all those documents in its possession.”

Stanley Kreejarly, a member of Seekon Pellekon’s leadership, corroborated the claim, adding another layer.

“FDA said it would not do business with us unless the community signed a contract with Liberian Hardwood,” said Kreejarly. Like Kumah, he presented no evidence.

“FDA recommended that we should do business with the Liberian Hardwood, and we agreed because it is the one overseeing the sector.”

Tarpeh Wluh-Sam, Seekon Pellokon’s leader, would not speak on the matter but said they needed development.

The claim that Merab is negotiating or pressuring locals for Liberian Hardwood is grave. Per the Community Rights Law…, the FDA does not negotiate contracts. Rather, it approves them. Negotiating for a company would violate the Code of Conduct for Public Officials, which prohibits the violation of any law and using official positions for personal benefit.

Merab did not respond to queries for comments on the allegation, but Akkari did, defending his company and the FDA’s boss. He denied that Merab favored Liberian Hardwood and that the people who made the claim were likely unaware of the matter.

“[Liberian Hardwood] reiterates that Hon. Merab never made any such intervention on its behalf vis-a-vis the people of Seekon-Pellokon for the management of their community forest(s),” said Akkari.

“[Liberian Hardwood] does not entertain any sliver of thought that Honorable Merab… would engage in flouting the law… and stoop to meddling in the award of Community [forest contract].”

‘Not a rocket scientist’

The FDA might have disapproved of Universe Forest Group. However, Liberian Hardwood may not have the capacity to handle Seekon Pellokon either.

Liberian Hardwood’s previous contract in the Bloquia and Neezonnie Community Forests ended disastrously. It left the Grand Gedeh communities with debts, broken promises, and hundreds of logs that are now rotting.

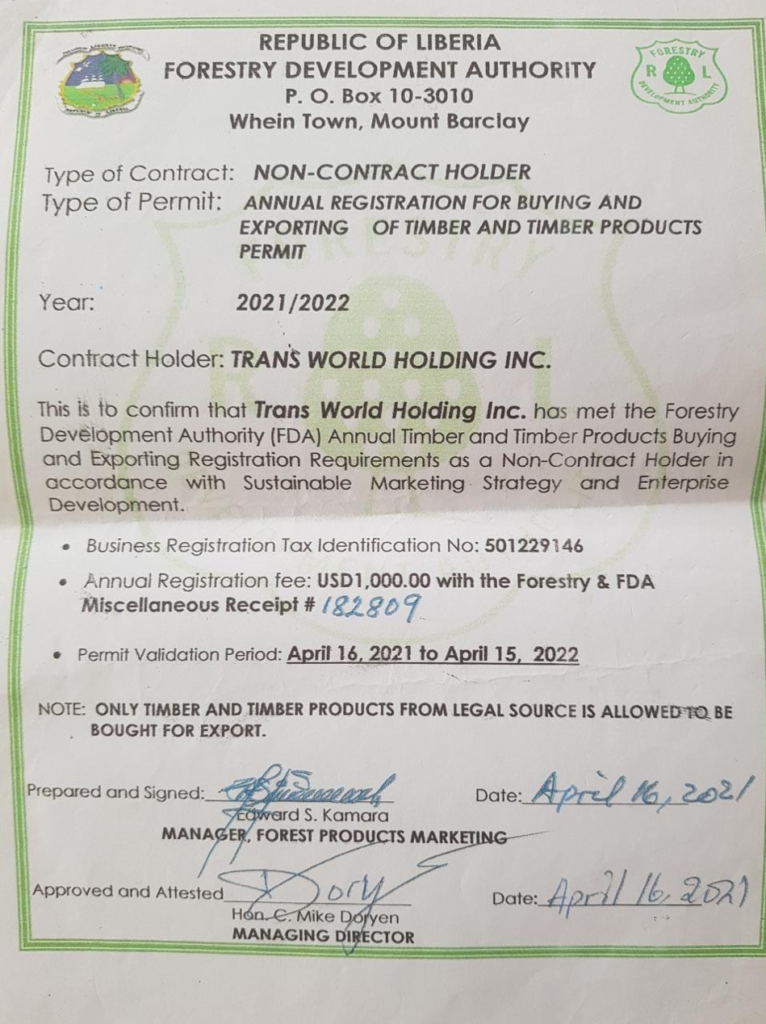

In 2016, the FDA halted Liberian Hardwood’s operations until it could export timber it had abandoned in the forest. Three years later, the company’s account was disabled in LiberTrace, the timber-tracking computer system.

Sampson Zammie, the secretary general of the community forests union, said he warned Wluh-Sam against contracting Liberian Hardwood. “I told him that he should not do it and if he does it, he will be doing it at his own risk,” said Zammie. Tarpeh confirmed having that conversation with Zammie, who is also Bloquia’s leader, promising to review Liberian Hardwood’s records.

Junior Kumah, another Seekon Pellokon leader, dismisses Zimmie’s warning. Kumah said that Seekon Pellokon had put in place a mechanism to avoid the Bloquia-Neezonnie experience. They would sign a five-year contract, the company would pay after production, and they would terminate the contract if Liberian Hardwood breached it, common safeguards in community forestry.

“I am not a rocket scientist to know whether Hardwood will fail or not. All I am telling you is that what happened in Bloquia will not be repeated here. What happened to John doesn’t mean the same thing will happen to Paul,” Kumah said.

Akkari denies any wrongdoing in Grand Gedeh, claiming he lost US$4 million there. He referenced a 2021 Supreme Court ruling that cleared Liberian Hardwood of US$90,325.15 in damages to Bloquia and US$123,332 to Neezonnie in a contract-termination lawsuit.

In the ruling, the Supreme Court said that a Grand Gedeh judge had “improperly” executed its initial verdict. “This was a petition for cancellation, which proceedings do not give awards, as is done in an action of damages,” read the ruling.

But the high court ordered that local people were free to sue Liberian Hardwood for damages, which they would never do. The ruling concluded by ordering the 7th Judicial Circuit Court to allow Liberian Hardwood to remove its equipment from the forest. The case was filed by A&M Enterprise Inc., which had subcontracted Liberian Hardwood for its contract with Bloquia and Nezonnie.

Logging amid controversies

There are other capacity concerns, as Liberian Hardwood is not the only company Akkari manages. The Lebanese is also the manager of Euro Liberia Logging Company.

Euro Logging operates the second-largest forestry concession in Liberia, covering Grand Gedeh and River Gee Counties, 254,670 hectares. Combined with Seekon Pellokon’s 44,989 hectares, that would be nearly 300,000 hectares, and one of the largest managed by a single individual in Liberia’s postwar forestry.

Obtaining community forest contracts has proved counterproductive in several cases for managers of large logging concessions. One example is Cesare Colombo, then manager of International Consultant Capital, which holds 266,910 hectares across Grand Gedeh, River Cess and Nimba and is the largest forestry concession in Liberia. Colombo acquired two community forestry contracts with Marblee & Karblee, and Gbarsaw & Dorbor in Grand Bassa and River Cess, but failed.

Campaigners said loggers were exploiting rural communities.

“My understanding is that some of these companies are taking advantage of the limited capacity of community members who are awarding these concessions to them,” said Andrew Zelemen, a campaigner for Euro Logging-affected and other communities, in 2022.

“Something is wrong somewhere…, and these companies need to tell us what they are doing with the Liberian people’s forests,” added Zelemen.

Akkari said he was unaware of the failure of individuals who run large concessions and community forests. Yet, he did not doubt handling the second-largest concession and Seekon Pellokon at once.

“[Liberian Hardwood] can affirmatively state that it has the capacity to operate such forest area(s),” Akkari said.

“In any case, however, the FDA does not give its [approval] to any arrangement unless it is satisfied that the prospective operator has the capacity…,” he added, though the evidence disproves this claim. The FDA has awarded several individuals multiple contracts, including four to a Singaporean family, after they failed their previous contract.

That aside, a review of the forestry sector last year found that it was unclear whether Euro Logging’s US$250,000 performance bond was sufficient. However, the review identified it as the company with, perhaps, the fewest issues in forestry.

Also, Akkari is disqualified from engaging in logging activities in Liberia, according to the Regulation on Bidder Qualifications. The regulation bars individuals who were involved in the logging industry before January 2006. They can only participate unless they confess their wartime wrongdoings to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and repay embezzled or unpaid funds.

There is no record that Akkari, who ran the Akkari Timber Inc. during the Second Liberian Civil War (1999-2003), whose contract was cancelled for noncompliance, met those requirements. He did not respond to queries regarding his wartime activities and Euro Logging’s capacity.

[Additional reporting from Oniel Philips from the Temple of Justice in Monrovia]

This story was a Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists (CoFEJ) production.