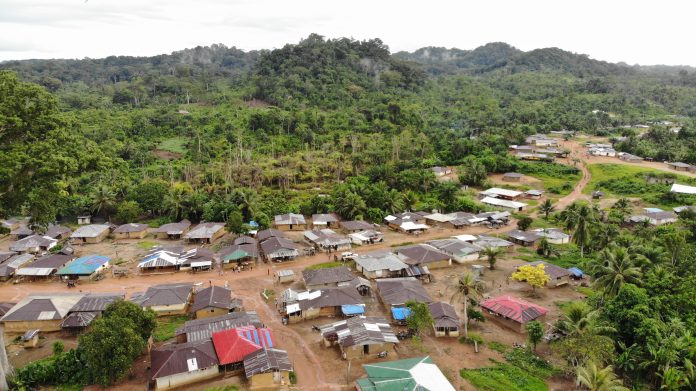

Top: Gboyonnoh Karmbo awaits the Liberia Land Authority to conduct a survey and confirm its land area. The DayLight/Derick Snyder

By Harry Browne

TITIYEN, Sinoe County – Gboyonnoh Karmbo could not progress in its quest to get a customary land deed without resolving a boundary dispute with the Kwiatuoh Clan. Gboyonnoh Karmbo argued the Klinlin Creek was the boundary but Kwiatuoh was firm on Gboyonnoh Karmbo’s side of the water, some 30-minute walk.

“Via oral testimonies, we were able to come together and identify one place,” recalls Harris Togba, the chairman of Gboyonnoh Karmbo’s land leadership. Togba speaks to The DayLight in Titiyen, one of four towns that own the land. The other three are Jogbawon, Chernyenkpo and Gbankpo. Predominantly Kru, it has a unique culture, with a traditional school for boys and girls to preserve their way of life and culture.

“We believe in the history of our people,” Togba adds.

Following the mediation of the NGO Foundation for Community Initiatives (FCI) and the Liberia Land Authority, both clans resolved the dispute, agreeing that the creek is the boundary. FCI has worked with the community since 2019. Its current work in the region is part of a US$4.45 million project funded by the International Land and Forest Tenure Facility, styled “Keeping the Promise.”

It has been five years since Gboyonnoh Karmbo, a clan with 1,300 plus people in the Jaedae District, declared its intention to acquire an ancestral land deed. It has established a land governance body—known as the Community Land Development and Management Committee (CLDMC). It had set up bylaws and a constitution and mapped its presumed land area.

With the Kwiatuoh Clan dispute settled, Gboyonnoh Karmbo had now established all the boundaries with its neighbors and completed that stage of the deed process.

“We together agree to clearly and finally establish the boundaries between our communities, and to desist from any further boundary conflicts concerning this area,” the MoU reads. It adds to the MoUs with Brutroh, Berh and Sayoh, another major dispute Gboyonnoh Karmbo resolved in 2020.

Next for Gboyonnoh Karmbo is the official survey after which the clan will be granted a customary land deed, marking the final requirement under the Land Rights Act. Liberia passed the law in 2018, recognizing customary tenure, a monumental right for the empowerment of rural communities.

Alexander Cole, FCI’s project coordinator, says the official survey would start this month, using special technology to cement boundary markers.

“FCI is happy that these communities will forever resolve land conflicts that existed because of conflict on traditional boundary markers,” Cole says.

The Land Authority says it has received resources from the Tenure Facility to “adequately” survey Gboyonnoh Karmbo, covering 13,462 hectares of land. Parley Liberia, a Bong-based NGO that works with FCI and the Margibi-based Sustainable Development Institute, confirmed that disclosure. The survey is scheduled for later this month.

“When it comes to this survey in Sinoe County, we are fully prepared to carry on this survey.” Dr. Mahmoud Solomon, assistant director for survey and mapping at the Land Authority tells The DayLight. “We do not want to survey with the old technology.”

Gboyonnoh Karmbo and Lower Bokon will add to the Sansen Clan as the communities that will have completed the legal steps to acquire a customary land deed. Sansen Clan completed its process earlier this year, while Lower Bokon will complete it alongside Gboyonnoh Karmbo.

‘We are the land’

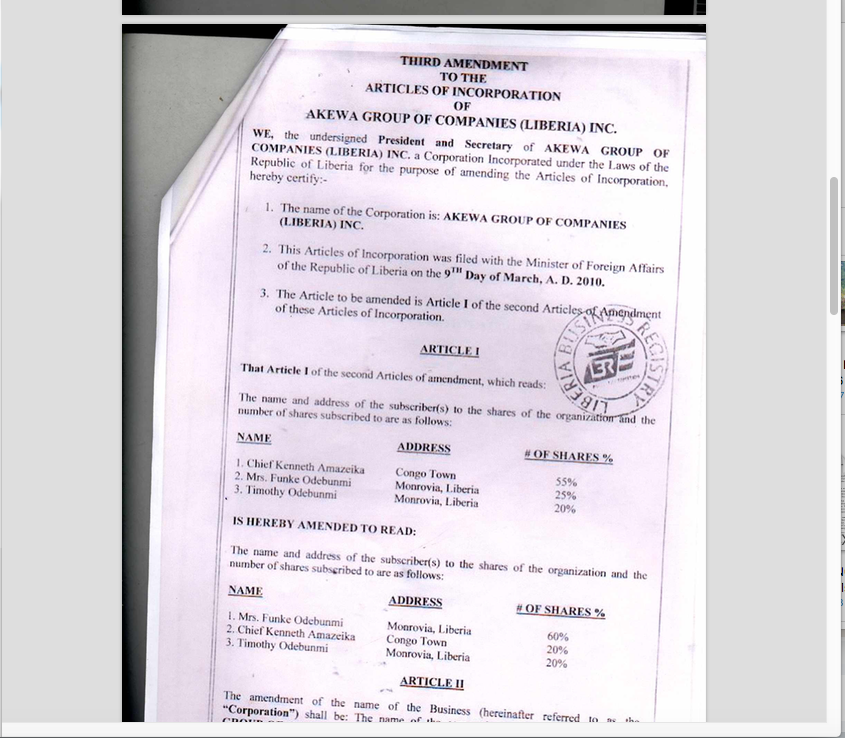

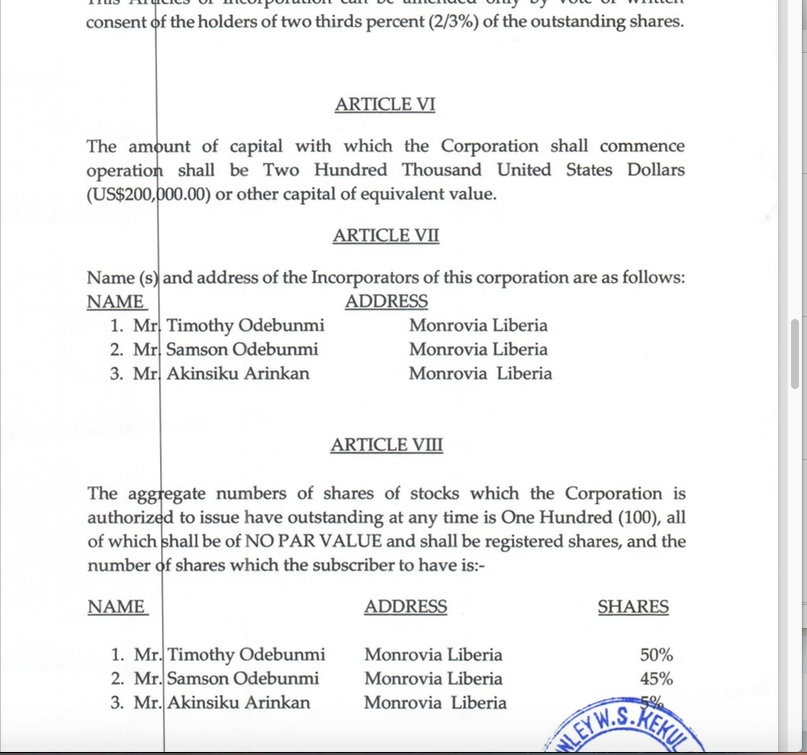

By law, when Gboyonnoh Karmboe finally formalizes its land ownership, it will become easier for the clan to benefit from the land directly. It will have the power to sit and discuss with would-be investors, a sharp contrast from the past, where rural dwellers were denied such benefits.

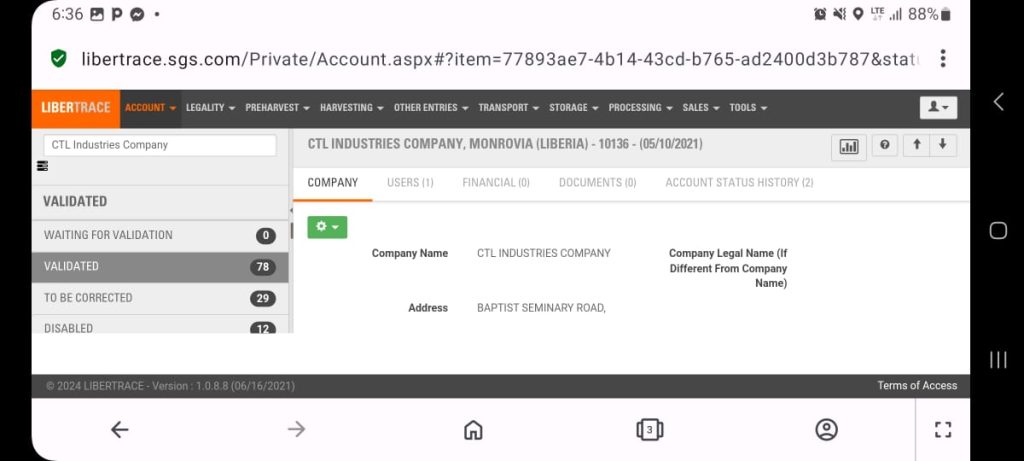

Gboyonnoh Karmbo has a forest and the potential for minerals. Next to the clan is an oil palm plantation run by Golden Veroleum Liberia (GVL). While there is no large-scale concession here, it currently hosts small and medium-scale miners, including illegal miners.

Reporters spot dredge miners on the River Dugbe, a form of mining prohibited by the Ministry of Mines in 2019, about the same time Gboyonnoh Karmbo started its process. There are two dredges on the right side of the Dugbe River Bridge. The miners had left their trail on the other side of the bridge along the riverbank, on farmland belonging to Francis Toe.

Toe admits to facilitating illegal mining. “When [miners] get the money, they give it to us and I take it to the committee board,” Toe says in an interview at his riverside home.

Togba, Gboyonnoh Karmbo’s chairman, promises that his leadership will combat illicit activities, using the community’s bylaws and constitution. “If we have the deed, we have to manage the land and go by regulations governing it,” he tells The DayLight.

“We are the land and we must have the land so that our generation now and the ones unborn can benefit,” Jah Nagbe Chea, Togba’s deputy buttresses. “This is our quest.”