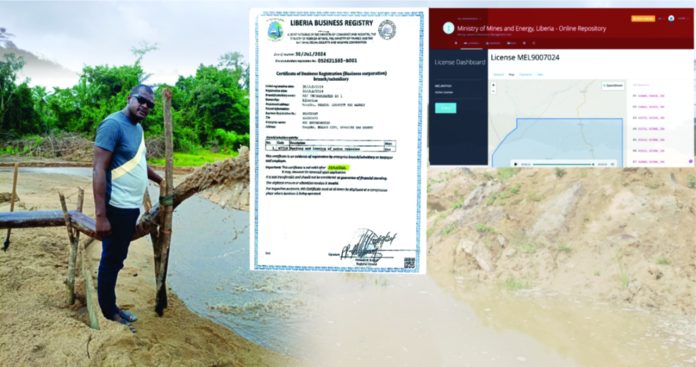

Top: A forest in Jacksonville, Bong County, in 2020. Picture credit: Harry Browne

By Winnie Oguerilam

As the world accelerates efforts to address climate change, carbon markets have become a central mechanism linking environmental stewardship with economic opportunity. For Liberia, a country endowed with vast forest resources and rich biodiversity, carbon markets offer a promising path to sustainable development, poverty alleviation, and international climate leadership.

Understanding Carbon Markets and Carbon Credits

A carbon market is a system that enables the buying and selling of carbon credits. Each carbon credit represents one metric ton of carbon dioxide (CO₂) either removed from the atmosphere or prevented from being emitted. These credits can be generated through a variety of projects and activities that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Examples include protecting existing forests, planting new trees, shifting to renewable energy sources, improving agricultural practices, and managing waste more sustainably.

Countries and companies that produce more emissions than allowed under regulations or voluntarily set targets purchase carbon credits to offset their excess emissions. There are two main types of carbon markets. The compliance market involves transactions regulated by governments under international agreements such as the Paris Agreement. The voluntary market allows businesses and organizations to buy credits to meet self-imposed environmental goals or demonstrate corporate social responsibility.

At its core, the carbon market places a monetary value on the reduction of carbon emissions, creating an economic incentive for conservation and sustainable practices.

Why Carbon Markets Matter for Liberia

Liberia is home to a significant portion of the Upper Guinea forests, one of West Africa’s most important and intact tropical rainforest ecosystems. These forests are critical not only for Liberia but for the global climate. They absorb vast quantities of carbon dioxide, helping to mitigate climate change. Beyond carbon sequestration, Liberia’s forests support biodiversity, regulate rainfall patterns, protect watersheds, and provide livelihoods for thousands of rural communities.

For Liberia, participating in the carbon market offers multiple benefits that align with environmental conservation and economic growth.

New Revenue Opportunities

Carbon credits represent a new and sustainable source of income. As global demand for credible carbon offsets rises, Liberia could generate millions of dollars annually by protecting its forests. This revenue could diversify the country’s economy, reducing dependence on traditional sectors such as mining, rubber, and timber, which often have significant environmental and social costs.

Community Empowerment and Development

Properly designed carbon market projects have the potential to directly benefit local communities, particularly those living in or near forested areas. Funds generated can be invested in schools, healthcare facilities, clean water systems, and livelihood programs. This approach can help reduce poverty, strengthen local governance, and ensure that the people who protect the forests receive tangible rewards.

Environmental Conservation

Carbon finance provides a strong economic rationale for preserving Liberia’s forests. By attaching financial value to standing forests, it becomes more profitable to conserve trees than to clear them for agriculture, logging, or mining. This not only helps combat climate change but also safeguards biodiversity, protects soil quality, and maintains essential ecosystem services.

International Climate Leadership

Liberia’s active engagement in the carbon market would enhance its global standing. It would demonstrate the country’s commitment to international climate agreements and sustainable development goals, strengthening its voice in climate negotiations and attracting further international support and investment.

Why Now Is the Time for Liberia to Act?

The urgency of embracing carbon markets cannot be overstated. The global appetite for carbon credits is growing rapidly. Governments, multinational corporations, and financial institutions are under increasing pressure to meet ambitious net-zero emissions targets. They are looking for high-quality carbon credits from countries with large, intact forests, making Liberia one of the few nations with the natural capital to meet this demand.

At the same time, Liberia’s forests face escalating threats. Illegal logging, mining, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure development put immense pressure on forest resources. If Liberia fails to develop alternative sources of income that reward conservation, the value of its forests will decline, and deforestation will accelerate.

Fortunately, Liberia has taken important steps in environmental governance. It has strengthened environmental laws and institutions, improved monitoring systems, and committed to international climate agreements. This progress lays the foundation for Liberia to develop transparent, accountable, and credible carbon trading systems.

Addressing Challenges for Success

Despite their promise, carbon markets come with challenges that Liberia must proactively address to ensure fair and sustainable outcomes.

Transparency and Accountability are essential to build trust among all stakeholders. Clear systems must track carbon credit projects, verify emission reductions, and ensure revenues are properly managed. Without these safeguards, carbon markets risk corruption, fraud, or mismanagement that could undermine Liberia’s credibility.

Community Inclusion is critical. Forest-dependent communities must be active participants in carbon projects. Their consent, rights, and benefits must be respected and prioritized. Excluding local people risks social conflict, project failure, and loss of forest protection.

Institutional Capacity must be strengthened. Liberia needs investment in technical skills, data infrastructure, and regulatory frameworks to navigate the complexities of carbon markets. Partnerships with international organizations and experts can accelerate this process.

Seizing a Defining Opportunity

Liberia stands at a crossroads. Carbon markets offer a unique opportunity to transform the country’s natural wealth into a foundation for sustainable growth and climate action. Rather than viewing forests as obstacles to development or sources of short-term profits through logging or land conversion, Liberia can treat its forests as living assets—generating income, creating jobs, supporting communities, and helping to solve the global climate crisis.

The decision is clear: Carbon markets are shaping the future of climate policy and economic development worldwide. Liberia must choose to lead rather than follow. By drafting a national strategy that balances conservation with economic needs, invests in strong governance, and includes local communities, Liberia can position itself as a leader in Africa’s emerging green economy.

The world is watching. Liberia’s forests are too valuable to lose and too important to ignore. With decisive action today, Liberia can secure a prosperous and sustainable future for generations to come.

The time to act is now. Liberia’s next chapter in sustainable growth starts with the carbon market.

Winnie S. Oguerilam is a Communications and Public Relations professional with a background in Environmental Science. She is currently serving as a trainee in the Political, Press & Information Section at the European Union Delegation in Liberia, where she supports public diplomacy and policy outreach. With experience in climate communication, advocacy, and community engagement, Winnie’s work bridges the gap between sustainability, governance, and public awareness. Her research and writings focus on environmental resilience and market-driven solutions to climate challenges in Liberia and beyond.