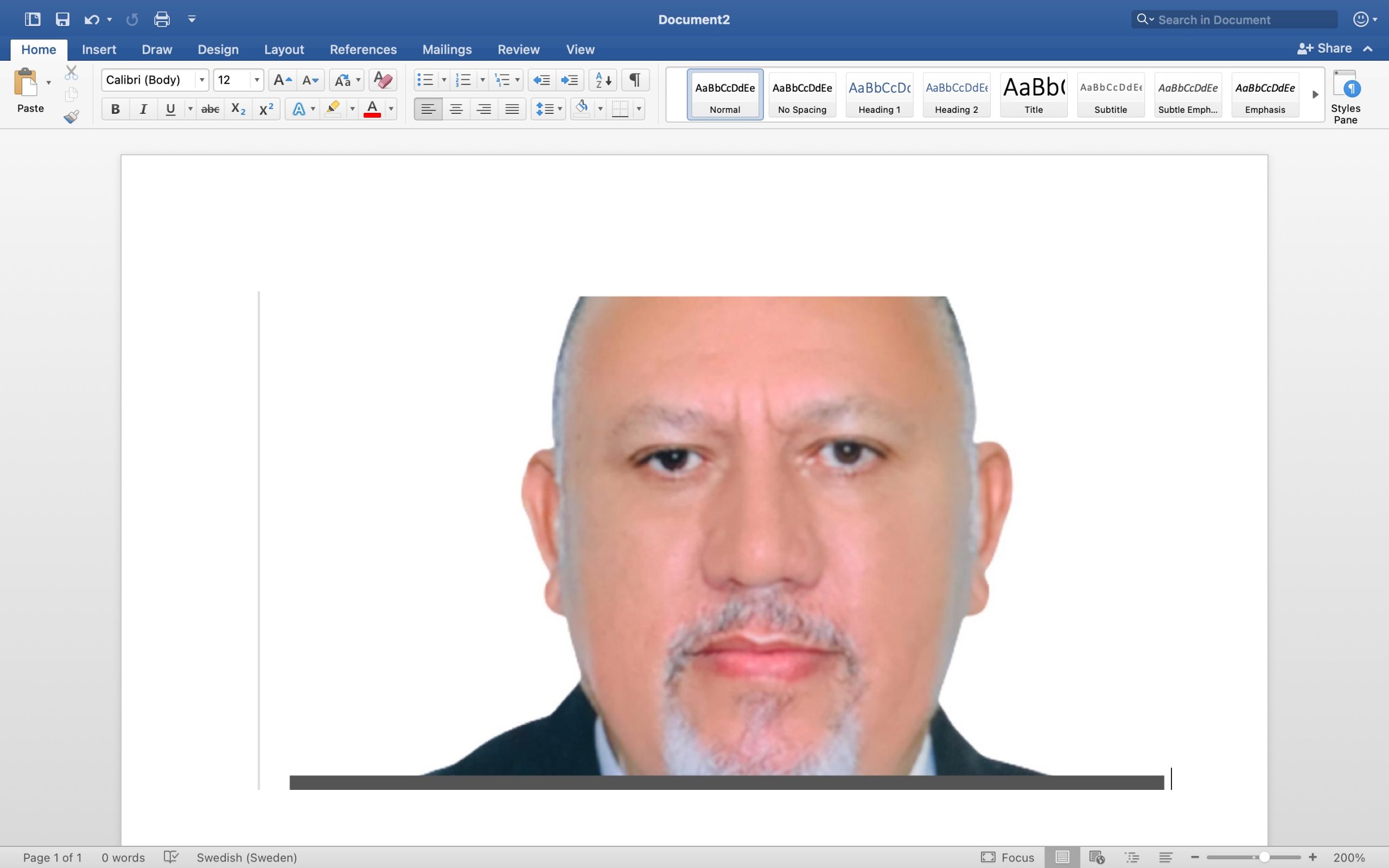

Top: Rudolph Merab, the new Managing Director of the Forestry Development Authority. Picture credit: The Liberia Timber Association

By James Harding Giahyue

- President Joseph Boakai over the weekend nominated Rudolph Merab as Managing Director of the Forestry Development Authority (FDA). Merab is an illegal logger and a critic of regulations and conservation efforts

- Merab and ex-President Charles Taylor were business partners. Militiamen and ex-combatants guarded Merab’s Liberia Wood Management Corporation (LWMC) in the early 2000s, according to Global Witness

- Bopolu Development Corporation (BODECO), another company Merab is associated with, participated in the biggest postwar logging scandal

- Merab is an outspoken cynic of regulation and conservation, things the FDA was established to enforce and promote

- Boakai has known Merab for over 50 years and served as chairman of the board of directors of one of Merab’s companies

MONROVIA – President Joseph Boakai has appointed Rudolph Merab—a wartime business partner of ex-President Charles Taylor, whose company participated in Liberia’s biggest postwar, logging scandal—as the Managing Director of the Forestry Development Authority (FDA). Merab is an outspoken cynic of conservation and postwar regulations, key pillars of forestry reform.

Boakai, who was inaugurated last month with a promise to fight corruption and uphold the rule of law, appointed Merab on Saturday following a month of speculations.

It is unclear whether Merab meets the legal requirements to head the FDA due to his well-documented illegal logging activities during Liberia’s deadly civil wars between 1989 and 2003. His company, Liberia Wood Management Corporation (LWMC), was the subject of international reports and was an issue during ex-President Taylor’s war crimes trial.

FDA’s Regulation on Bidder Qualifications partially debars wartime businesspeople such as Merab, who held a forestry contract before 2006, from conducting logging activities.

The regulation requires wartime loggers to file a sworn statement with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), admit their illegal activities and cooperate with the FDA to recover funds the government lost due to their illegal activities. However, the regulation is silent on whether or not a wartime logger is eligible to head the agency.

Also, Merab, who has a degree in physics, does not meet the educational qualifications for the job. The FDA Act requires the head of the agency to be “professionally educated in forestry.”

Campaigners had called on Boakai to respect that clause in the FDA act as part of his expressed quest for respect for the rule of law.

“At this present state of Liberia’s forestry industry, it needs someone with the necessary skills, contact, and connections… to turn the forestry sector around… beyond mere logging,” communities affected by logging contracts said in a statement last week.

“The sector is at a critical juncture, as numerous initiatives have failed to meet expectations over the past six to 10 years,” the statement added.

Boakai’s relationship with Merab goes way back. They met at the College of West Africa, with Boakai graduating in 1967 and Merab five years thereafter. Boakai later served as chairman of the board of directors of LWMC, sources, including Boakai’s campaign website, show.

Merab declined an interview with The DayLight.

Merab, the wartime logger

LWMC was founded in 1988 with Merab’s 10 percent share among a list of shareholders that included his late brother Edward Merab. It held a contract for Grand Cape Mount and Lofa. By the end of the Second Liberian Civil War (1997 – 2003), LWMC valued between US$500,000 and US$1 million and had about 300 workers, according to international investigators.

LWMC’s properties in then-Lower Lofa, Bomi and Grand Cape Mount Counties were protected by ex-combatants and armed militiamen, Global Witness reported. Within the first six months of 2000 alone, LWMC exported 12,810.062 cubic meters of logs, according to FDA records.

In 2001, Merab told an American publication that LWMC shipped small Liberian timber to the United States. Oriental Timber Corporation (OTC), the forerunner of Taylor’s timber and arms trafficking syndicate, exported to the United States.

Between 1999 and 2003, LWMC owed the government over US$1.3 million, according to a report by the Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (LEITI). The Taylor regime waived the amount, according to an email thread linked to the Ministry of Finance. Then Minister of Finance Nathaniel Barnes told a legislative inquiry that the regime had waived Merab’s arrears “to save 300 jobs.”

Rebels of the Liberia United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD), which had launched an armed incursion against Taylor, attacked LWMC’s premises in Gbarpolu in the 2000s.

The rebel told United Nations personnel they wanted to discourage Merab from doing business with Taylor, according to a 2001 UN Security Council report. The UN would sanction Liberian timber adding to a string of arms embargoes against the country.

A review of the forestry sector in 2005 found, “At least 17 logging companies either supported militias in Liberia, participated in, or facilitated illegal arms trafficking, or aided or abetted civil instability.”

The review found that all forestry concessions, including LWMC’s, had been illegally awarded. This prompted President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf to cancel all the existing forestry contracts in 2006. Her administration awarded new contracts, a precursor for the lifting of the UN sanctions that same year.

At his war crimes trial in 2010, prosecutors at the Special Court for Sierra Leone cross-examined Taylor on an accusation that he channeled money through Merab to rebels in Sierra Leone. Taylor denied the accusation but was eventually found guilty of running arms and smuggling diamonds with the Sierra Leonean rebels. He is serving a 50-year sentence for his role in that war, which killed some 70,000 in Sierra Leone.

An estimated 250,000 people died in Liberia in wars that were fueled by a scramble for logs and other natural resources, the TRC said. Unlike Sierra Leone, Liberia has yet to address crimes committed during its wars.

Merab’s Postwar Illegal Deeds

Bopolu Development Corporation (BODECO), another company Merab owns, was involved in the Private Use Permit (PUP) Scandal of 2012 in which 2.5 million hectares of forestlands were illegally awarded to logging companies.

A government-backed inquiry found that BODECO was awarded 90,527 hectares in Bopolu District, Gbarpolu County, the fifth-highest area of the 66 illegal permits.

BODECO did not have the financial and technical capacity to conduct logging in Liberia, the inquiry found. The permit was issued in BODECO’s name while the Korninga Chiefdom had submitted the application.

BODECO and the FDA also violated requirements of the permit. The permit is issued only for forests on private lands. However, investigators found that Bopolu was communal land, not private.

“Both FDA and BODECO knew or should have known that they were executing a contract with material falsehood…,” investigators said.

Following the inquiry, BODECO’s and the other 65 permits were revoked and a moratorium imposed on the forest contract remains in place. Moses Wogbeh, the FDA Managing Director who oversaw the scandal, was dismissed and prosecuted.

BODECO failed to provide a school, roads, harvesting and land rental fees, and a clinic, leaving hundreds of logs to rot.

George Ballah Sumo, the Paramount Chief of Korninga Chiefdom blamed Merab and other BODECO executives for dashing the hopes of locals.

A cynic of regulations and conservation

Wartime logging and the PUP Scandal aside, Merab is an outspoken critic of forestry regulatory regime and conservation. Forestry has the most regulations in Liberia, while the conservation is one of the pillars of the sector’s reform agenda.

Merab’s appointment comes at a time of rising violations of forestry laws and regulations. Illegal logging, unsustainable harvesting practices and disregard for communities’ rights are commonplace. A recent review of the sector found 11 concessions illegal and the FDA complicit in the illegalities.

In a 2015 interview with the African Report, Merab said sustainable logging had not been achieved due to “taxation and restrictive legal regime.”

“Since the new logging restrictions, most of the rural economy has ceased, impoverishing the rural areas,” Merab said in the interview.

Merab also criticized a deal between Liberia and Norway in which Liberia received US$150 million to halt deforestation. Merab argued that the agreement hurt investors, businesspeople, and logging employees. He promised to campaign against it on grounds that loggers were not consulted, comparing it to the Sirleaf administration’s decision to cancel his and other logging contracts back in 2006.

“We Africans got to think outside the box,” Merab, the president of the Liberia Timber Association up to his appointment, told FrontPage Africa in 2017. “The neo-colonial issue cannot continue to affect us,” he said. “You got to learn to stop letting people fool us. They’re the ones exploiting us, especially Norway.”

[Additional reporting by Charles Gbayor and Esau J. Farr, Sr.]

This story is a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).

Facebook Comments