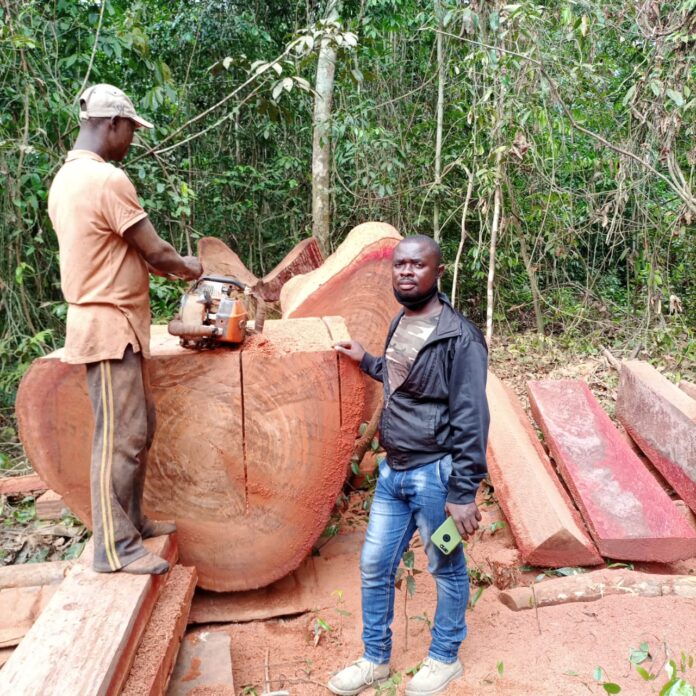

Top: A tree, locals said, was felled by Masayaha Logging Company outside the Worr Community Forest. The DayLight/James Harding Giahyue

By Emmanuel Sherman

Editor’s Note: This is the first of a series on illegal logging activities by Masayaha Logging Company, which works in Grand Bassa County.

TARR TOWN, Grand Bassa County – Mid-last year, Masayaha Logging Company asked chiefs and elders of Doe Clan in Compound Number One to harvest expensive logs in their forest in order to build roads, handpumps and a townhall in that community. But the company wanted the deal kept a secret.

The villagers agreed with the terms, adding a fee of US$5 on each cubic meter of red hardwood used for railroad ties and bridges.

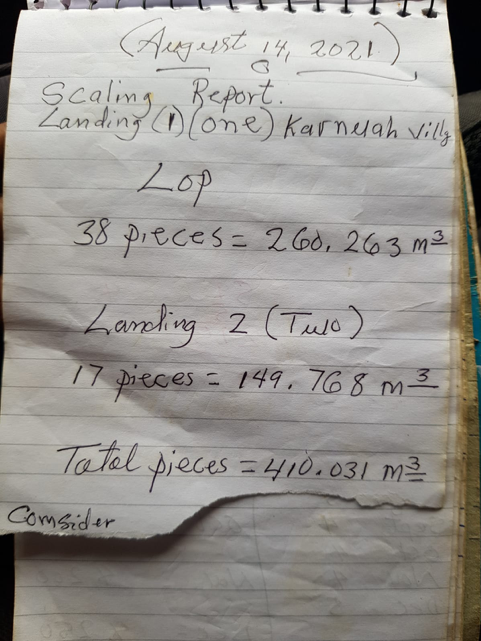

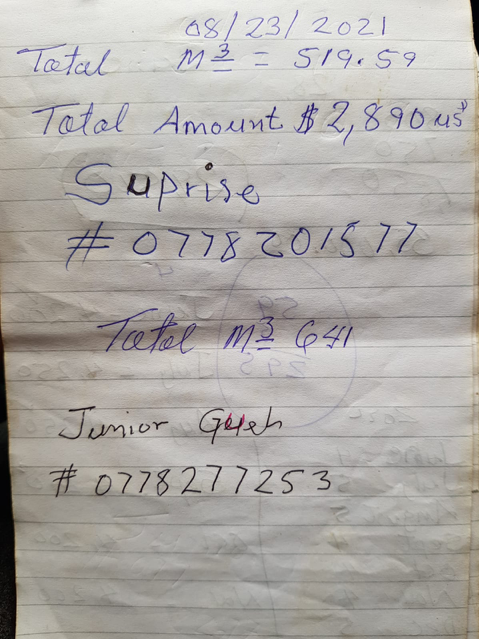

“We told them to connect the road from Tarr Town to Kpana Town because the people there are suffering,” recalled Daniel Tarr, one of the elders who brokered the deal. The next month, Masayaha begin felling some 641 cubic meters of the red ironwood, according to the locals’ record of the harvesting.

“The company wanted some ekki [woods],” added Junior Gueh, a townsman who also works for the company and helped craft the deal.

But the deal was illegal, as the forest adjacent Tarr Town is outside the Worr Community Forest Masayaha legally operates. It is one among a string of illegal operations the Lebanese-own firm has run in that region in the last two years, involving five towns. It has been documented that Forestry Development Authority (FDA) has taken no required actions against the company.

Masayaha has a 15-year agreement to operate the Worr Community Forest. Magna Logging Corporation, owned by Liberian businessman Moley Kamara, originally holds the contract for the forest but appears to have subcontracted it to Masayaha. The forest covers 35,337 hectares in Compound Number One B but the company traveled about 100 kilometers to the Doe Clan in Compound Number One A to harvest first-class logs. It said there were not many of that species trees in the Worr Community Forest, according to several villagers we interviewed.

Mary Beeweh, an elderly woman in Zolah Town, told The DayLight the company harvested logs in the forest there in 2020. Beeweh said Ali Harkous, Masayaha’s CEO visited the town. Her description of a bald, bearded Lebanese man matches Harkous’ figure.

Masayaha also felled an unspecified number of logs in Lolo Town last year, according to residents. We told them ‘If you fix our two bridges here, we will give you the logs [you] want,” said Solomon Kpolon, an elder of that town. “The first was 17 logs but the second one they took it overnight we did not know about it.” This reporter saw some of the logs the villagers said Masayaha felled in the forest not far from the town.

In Vorlorgor, a village next to Tarr Town, villagers seized the company’s machines after it felled 17 trees, according to John Garbleejay, an administrator of that town. They later allowed illicit activities to go on after the company promised to pave the main route that leads into the community, Garbleejay said.

Harvesting outside a contract area is a grave violation in forestry. A company’s penalties for such an offense include a fine in United States Dollars upon conviction by a court.

There is evidence that the FDA has known of Masayaha’s illegal logging deals from its first known offense in 2020 but ignored them. The agency conducted an inquest in August that year on several logging violations in Grand Bassa, River Cess and Nimba, those of Masayaha. Investigators recommended an “appropriate action” against it but that has yet to happen.

And that, too, was not the first time the FDA heard about Masayaha’s violations and failed to act. Several months earlier in 2020, Reuben Barnie, one of the villagers, informed FDA about the incident. Barnie had spotted a Masayaha truck transporting logs from Kweezah, the home of the descendants of people who were evicted from the land Firestone occupies today. Knowledgeable of the company’s contract area, Barnie raised an alarm.

“We are calling your attention to please come in our district to carry on an investigation so as to stop future embarrassment,” Barnie wrote in a May letter last year. He took to a local radio station and engaged the company. He then followed up with numerous phone calls to Joseph Tally, FDA’s deputy managing director for operations, whose recordings Barnie gave to The DayLight.

“Barnie how you doing?” Tally can be heard in one of the recordings.

“Yes, we still keeping our fingers crossed for the verdict,” Barnie responds, referencing a previous conversation in which Tally promised to take action against the company.

“Keeping your finger crossed for what?”

“For the verdict. The people went to do the investigation.”

“I told you we have already suspended the people activities.”

Société Générale de Surveillance (SGS), a Switzerland-based firm that developed Liberia’s log-tracking system or LiberTrace, also reported the illegal operation. The development of the system was crucial to forestry reform, as importing countries such as the European Union and Great Britain demanded legal timbers. It is now turned over the majority of its responsibilities to the FDA’s legality verification department (LVD).

Like Barnie, Stephen Toomey, one of the residents of that area, reported the case to the FDA. This reporter witnessed Toomay raise the issue in a Worr Community Forest meeting in October last year. Joseph Kpainay, an FDA ranger assigned in the region, then asked him to file an official complaint with the agency’s regional office in Buchanan. Toomay did it days after the meeting but got no response. Kpainay acknowledged receipt of Toomay’s letter.

“The concerned citizens of the affected communities are therefore calling on your good office to promptly investigate, intervene and promptly provide an appropriate solution…,” Toomay’s letter read.

News of the illegal logging Masayaha carried out last year made it to FDA’s headquarters in Paynesville. In August, the same month as the illegal felling, SGS reported on the incident.

“During the month, some felling out of CFMA Worr concession was seen again !!!,” SGS said in a report. It also criticized the FDA for approving the company’s harvesting plan that year without a required five-year plan, a breach of the Code of Harvesting Practices and Standard Operation Procedure.

“Surely, because no action was taken from the felling out of concession at… Worr reported by SGS a year ago, that illegality is still going over there.”

But amid SGS’ report and Barnie’s advocacy, FDA permitted Masayaha to export logs that could have included the stolen woods. Between 2020 and last year, Masayaha exported 365 logs, 360 of them ekki woods, according to official shipment records. In fact, it approved three of the company’s shipments about the time of the Garkpa Charlie Town illegal logging, according to the SGS report.

In normal forestry practices, the FDA is supposed to trace every log the company harvests back to its stump to make sure the logs were legally sourced before they are transported.

Also amid the mountain of evidence against Masayaha, FDA should have sought court orders to confiscate and auction them. It should have also fined the company two times and four times the prevailing international price of the volume of logs it harvested in Kweezah and Garkpa Charlie Town, respectively, according to the Regulation on Confiscated Logs, Timbers and Timber Products. The current price set by the FDA ekki woods is US$210. The company could have been slapped with a 12-month prison term if convicted by a court.

Barnie called Tally, furious that the logs had made it out of the community and the company had not been fined for the violation. “Those logs are at the Port [of Buchanan] and are taken from where they have no concession. I’ve been calling some eight, nine months ago on the issue in Number One Compound. Now the people are carrying the logs,” Barnie can be heard in the recording, threatening to protest at the port to stop the shipment.

It was unclear how many logs Masayaha harvested in all its illegal operations. Neither SGS nor the FDA provided that information. However, the villagers’ records of last year’s felling seen by The DayLight put that number to 641 cubic meters. The elders had designated Mathew Gaywheon, a townsman, to represent them during the operation. If Masayaha had been convicted for its 2020 illegal harvesting and the one last year, it could have paid over half of the million United States dollars for a second offense.

There were signs of the operation in the area. We saw stumps of the felled trees. The elders of the town said a short piece of log lying adjacent to the palaver hut under which we conducted interviews was a remnant of the operation. A number of logs were still at the site of an open field, where villagers said Masayaha’s workers piled up the woods. Earthmovers’ trails adorned the site, despite a year of downpour.

The area matched the one in the pictures Toomay shared with us of the unlawful operation in Garkpa Charlie Town. One of the pictures shows a Masayaha vehicle parked next to the thatched kitchen where we conducted some of our interviews. Others reveal the company transporting some of the logs with official identification tags, indicating they had been registered into the FDA’s database.

The FDA did not grant The DayLight an interview on the matter. We emailed the agency earlier this month and received a response last week from Tally, who scheduled the interview for Tuesday. However, he did not turn out at the time of the interview he had set. Cllr. Yanquoi Dolo, the head of FDA’s legal department, declined to speak on the matter.

Kamara, the CEO of Magna, also declined to speak on the matter.

Harkous did not respond to queries sent him via WhatsApp for comments on his company’s illegalities.

This Story is a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).