Top: Some of the illegally harvested logs. Picture credit: Independent Forest Monitoring Coordination Mechanism

By James Harding Giahyue

BUCHANAN, Grand Bassa County – The Forestry Development Authority (FDA) has accepted a Supreme Court mandate to allow a company to export a huge consignment of logs it had illegally harvested. It brings to a close more than one year of a legal battle that has shed light on widespread irregularities in Liberia’s forestry sector.

The Second Judicial Circuit Court in Upper Buchanan had issued an arrest warrant for officials of the FDA after it failed to adhere to the high court’s decision to uphold the lower court’s ruling in favor of Renaissance Inc. The firm had sued the FDA after the agency seized some 14,000 cubic meters of logs valued at an estimated US$4.17 million.

Sheriffs last week arrested Atty. Gertrude Nyaley, the technical manager of FDA’s legality verification department (LVD), which manages the system that tracks logs harvested and exported out of Liberia. Nyaley was later released on bail by her lawyers, with the agency scheduled to appear before the lower court on Monday, according to court filings.

At the proceedings on Monday, Cllr. Abraham Sillah, the head of the FDA legal team, asked the court for 10 days for the export to happen. The court granted that petition, fining Nyaley, Harrison Karnwea, the chairman of its board of directors, Managing Director Mike Doryen and his two deputies, US$300 each. It also fined Cllr. Yanquoi Dolo, FDA in-house lawyer, US$100. It said it would jail officials of the agency if the logs were not shipped by that time.

“No department of the government other than the Judiciary shall exercise judicial function,” Judge Peabody said, according to court documents. “The [actions] of the Forestry Development Authority and its managers are usurping the functions and have interfered with and is an act of reviewing the judgment of the Supreme Court and this court.”

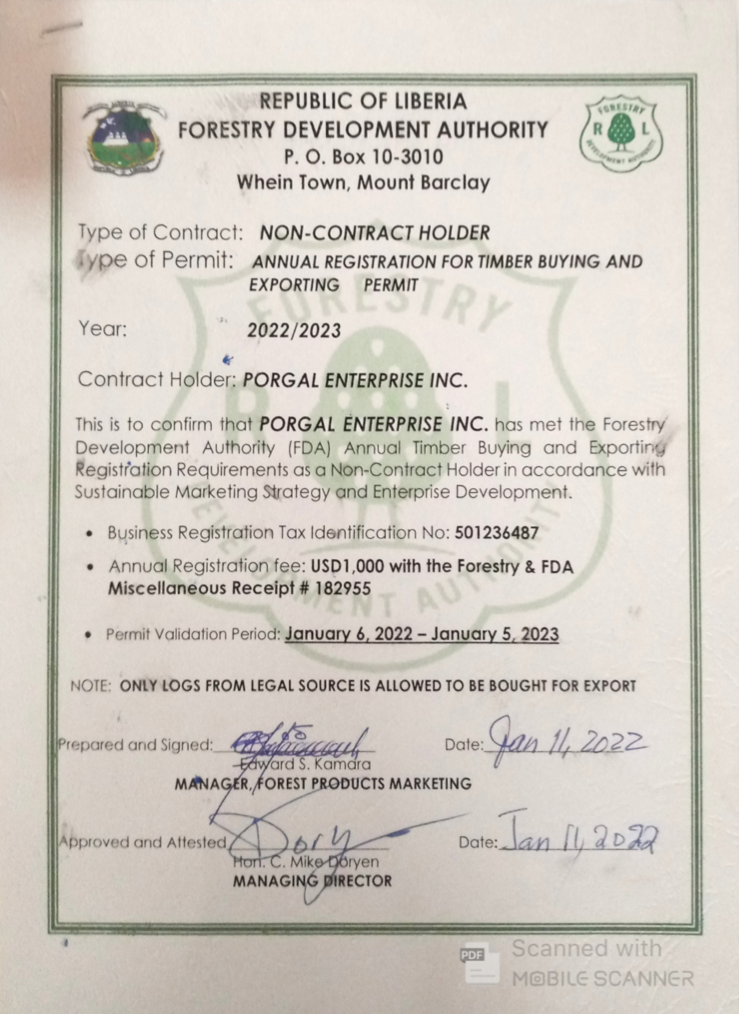

The court also accepted the FDA’s request not to export the controversial logs through the tracking system called LiberTrace. The computerized system uses barcodes to trace timber from its sources to its final destinations. It is an integral part of Liberia’s forestry reform agenda, a foothold of the country’s trade agreement with the European Union, called the Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA).

“I am happy that the law is about to take its course,” said Aaron George, Renaissance’s CEO in a mobile phone interview.

Renaissance won the case after the court upheld a six-man jury unanimous verdict to allow Renaissance to export the logs. The court agreed with the company that disallowing its logs from being shipped having already paid a US$105,000 fine would have amounted to a double punishment or double jeopardy. It is a defense in Liberian law that prevents a person from being tried again for the same offense.

After that verdict, the FDA filed an appeal at the Supreme Court, which was followed by a Renaissance motion for dismissal. The FDA did not respond to that petition, leaving the high court to dismiss the appeal.

“The agencies of the government of Liberia, though exempted from filling an appeal bond, they are required to strictly abide by the other mandatory steps enumerated in the appeal statute for the completion of an appeal,” the Supreme Court said in the ruling on November 4 last year.

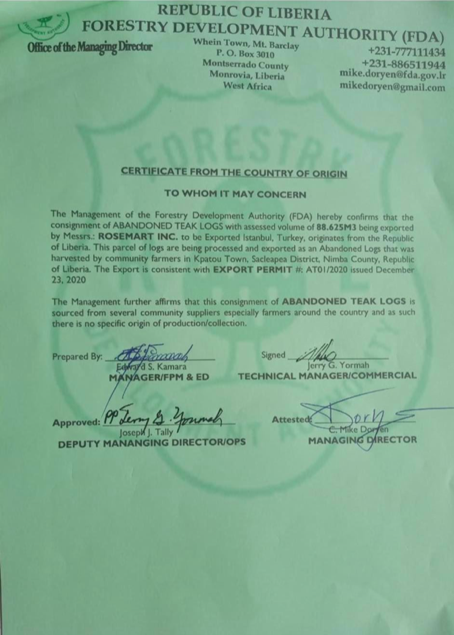

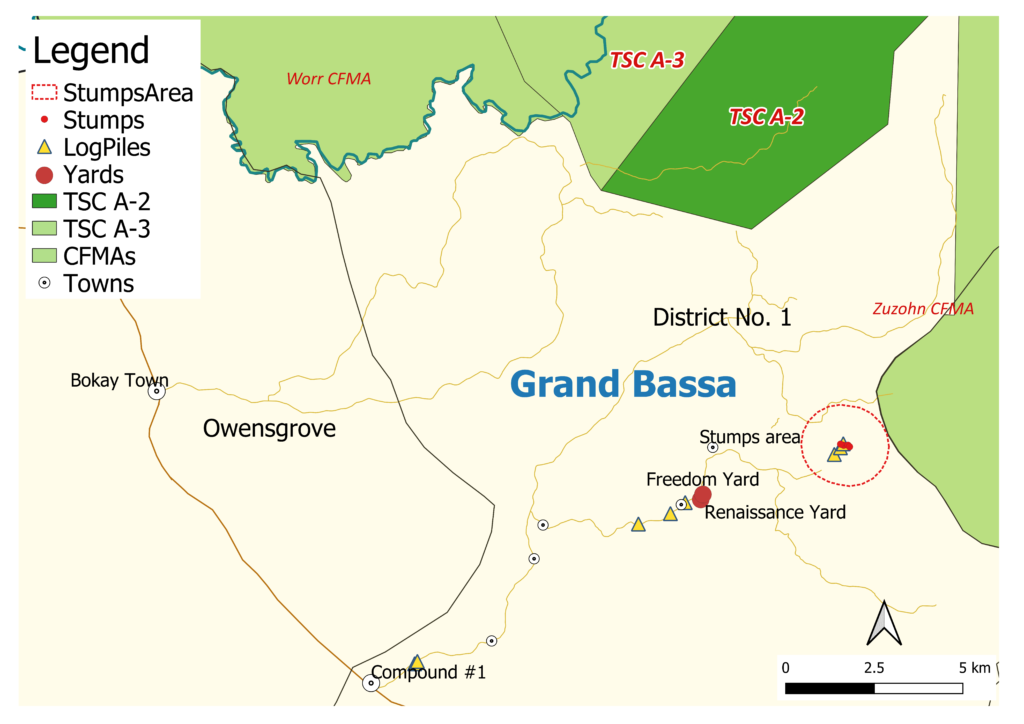

Renaissance Inc. harvested the logs outside its concession area known in the logging industry as timber scale contract area two or TSC A2, located in Compound Number Two, Grand Bassa County. Lacking a trace, FDA technicians found it impossible to register the wood into LiberTrace. Société Générale de Surveillance (SGS), a Swiss firm that co-manages the system, declined to enroll the timber, drawing the Supreme Court’s ire.

Monday’s decision is expected to anger more than a dozen international NGOs who called on the FDA to remain firm in its decision not to allow the logs to be exported. They come from the United States, European Union countries, the United Kingdom, and China three regions with a vested interest in Liberia’s forestry sector, investing millions.

“We are encouraged by the FDA taking action to stop illegally sourced timber being exported, and strongly support its staffs’ actions,” the organizations said in a joint statement on Sunday.

“We are extremely disturbed that the Liberian courts, instigated by logging company Renaissance, seem intent to punish FDA staff for doing their duty,” the statement added.

In 2021, an investigation by a group of civil society organizations found that Renaissance Inc. had harvested the logs under the pretext that it was paving a road in that area. It said all the logs were ekki wood (Lophira alata), first-class redwood currently selling for US$298 on the international market.

Two years before that, Société Française de Réalisation, d’Etudes et de Conseil (SOFRECO), a European Union-commissioned auditor based in Paris, urged the Ministry to investigate TSC A2.

“The mere fact that an operator took the risks of felling such an important volume of logs illegally provides a high probability that the operator was confident in the possibility to export the illegal logs, which raises questions for further consideration,” SOFRECO said in a November 2019 letter to major players in the forestry sector.

The ministry investigated the illegal harvesting but has not published its report for over three years on. The international NGOs called on the ministry to release the document.

“We call upon the Government of Liberia to follow the law, publish the official investigation report by the Ministry of Justice into the Renaissance case, and use the evidence provided in this report, to guide their decisions,” the group said.

Minister of Justice Cllr. Musa Dean told The DayLight “Findings [of the report] were released to the appropriate agency and all concerned.”

In March last year, the FDA canceled TSC A2 and six others in Bassa, Grand Cape Mount, Gbarpolu and Bong after they outstayed their legal lifespan. Communities affected by TSC A2 and the other concessions have not received their benefits.