Top: Kpokolo in plain sight in Gbaryama, Gbarpolu County. The DayLight/James Harding Giahyue

By James Harding Giahyue

MONROVIA – Last week, the two Turkish nationals were arrested in Ganta, Nimba County for their alleged involvement in illegal logging activities in that region.

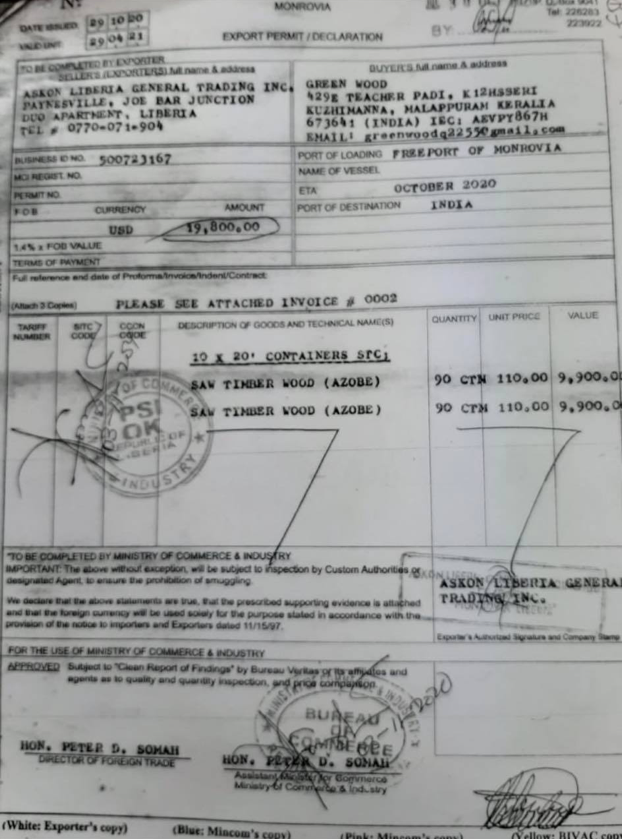

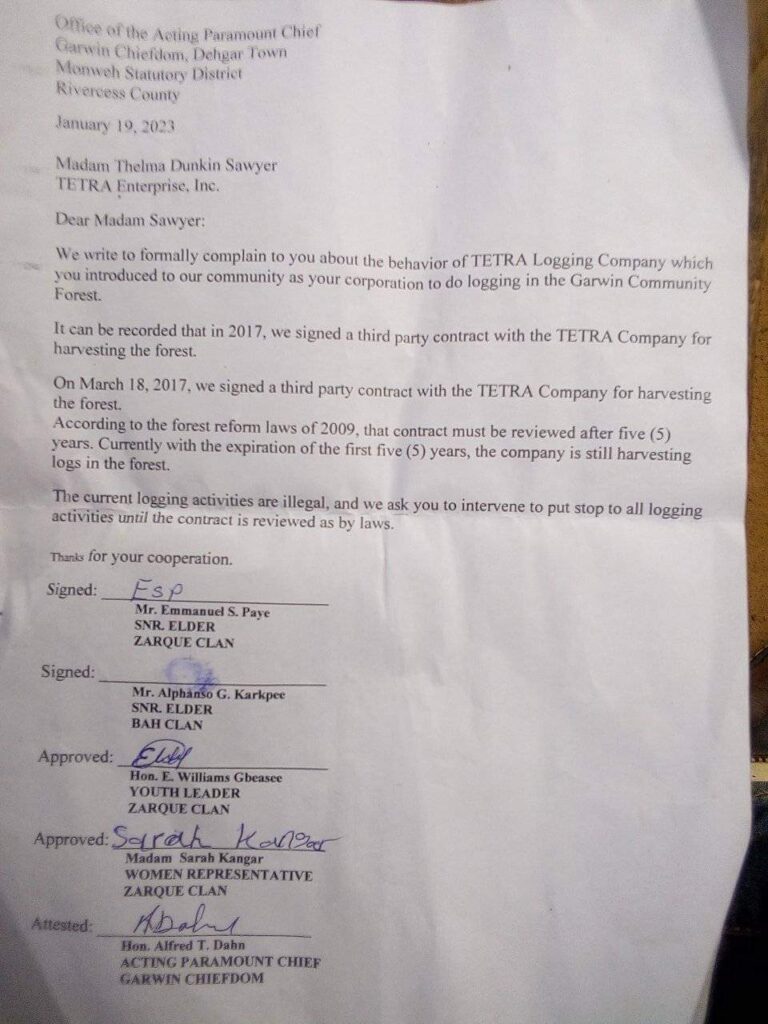

Police finally picked up Hasan Uzan and Umit Gungor after a couple of days on the run. Hasan Uzan and Gungor are part of Askon Liberia General Trading Incorporated. The company violated the terms of its sawmill permit by engaging in harvesting and exporting of thick timber, commonly called Kpokolo, according to the Forestry Development Authority (FDA). The FDA had banned the company and barred Hasan Uzan, Yeter Uzan and Faith Uzan, its co-owners from forestry activities.

Kpokolo, the most common illegal logging operation in the country, is largely responsible for the infamy of Liberia’s forestry sector today. In February, the FDA said it banned kpokolo after a string of reports of irregularities by The DayLight.

So far, here is what we know about Kpokolo:

Kpokolo began in the 2010s

Kpokolo started in Liberia somewhere between 2010 and 2012, according to players in the informal subsector. One experienced chainsaw operator in Gbarpolu said a Malian national introduced it in Kinjor, Grand Cape Mount County.

Two big players in the underground subsector said it started around the mid-2010s or so. One said Sierra Leoneans introduced it here in 2015, while the others said 2016. A number of receipts and other documents, obtained from kpokolo producers support the dates.

Kpokolo means ‘thick and heavy’ in Kpelle

The word Kpokolo roughly translates “thick and heavy” in the Kpelle language. That is a reference to the nature of the timber, which are squared, compact and require an entire football team or a machine to lift it up.

Kpokolo dimensions range from anything between three inches high to 10 inches long, according to receipts related to the transportation of the wood. The most common measurement of the wood is five inches high, 10 inches wide and 12 inches long.

Shaped to Fit Neatly into a Container

Kpokolo timber are produced in square form so that they can fit neatly into containers. The DayLight has obtained a number of photographs from social media showing a host of kpokolo being packed into containers.

Kpokolo Advertised on Social Media

Looking for kpokolo managers and loggers? Check social media, particularly Facebook.

One example is Emmanuel Gongor, a serial kpokolo logger in Nimba County. Gongor’s Facebook posts show different aspects of his kpokolo operation. Some show him heading on bad roads, piling huge pieces of kpokolo and others show him and some men loading a truck with the wood. Perhaps, the coolest picture shows a bottle of water on a flat cutoff of a log with the caption, “Iroko wood for sale.” Iroko is a first-class timber.

Kpokolo operators use WhatsApp, too. For example, Hasan Uzan, one of the Turks arrested by the police and Varney Marshall, a former FDA ranger assigned in Bomi County, used WhatsApp.

Uzan has a number of Kpokolo-related pictures on his profile. It brandishes: “Tropical Timber Center West Africa.”

Marshall used his WhatsApp differently. He does not have pictures of his kpokolo operations there. However, last year, he shared videos and pictures of the operations with Isaac Richmond Anderson, a former staffer of the Liberian consulate in South Korea in a bid to partner with Anderson. Marshall was later relieved of his post, and he and Anderson have been indicted in another illegal logging deal.

Kpokolo Thrives on Misconceptions

Once you are a Liberian, and you have an article of incorporation and business registration, you can produce kpokolo, according to major kpokolo loggers The DayLight has interviewed. There is no need for an environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA), a contract, a harvesting certificate and other requirements, according to them. Once you have the aforementioned documents, you are good to go.

Amid a lack of awareness of forestry legal frameworks, kpokolo players are inspired by these misconceptions. Legally, one must have a contract, an agreement with a community that has the right to enter an agreement, conduct an ESIA, obtain harvesting authorization and many other things. Also, transporting and exporting timber hinges on other requirements kpokolo operators sidestep.

Kpokolo Operators Target Expensive Wood

Kpokolo producers do not just go for any wood. They target hardwood, used for shipbuilding and outdoor construction, such as bridges. These timber contain a lot of oil in them, which makes them water-resistant and durable, according to experts.

There is a huge possibility that the kpokolo timber you have seen are ekki (azobe), dahoma and Iroko (Kambala). To give you some context here, a cubic meter of ekki sells for US$281, according to the International Timber Trading Organization (ITTO).

In some cases, kpokolo operators harvest class B wood such as Tali (sassawood).

Kpokolo Smugglers Target Asian Markets

Smugglers of kpokolo avoid Europe and target Asian markets, mainly China, India, Bangladesh and Vietnam.

The kpokolo underground trade avoids the European markets, which trade only legal timber. Liberia has a trade deal with the European Union called the Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA), which requires only legally and sustainably sourced wood for the European market. The smuggling of kpokolo is a violation of the VPA.

According to a number of online marketplaces or B2B platforms, Liberian businesses have exported containers of sawn timbers to those Asian countries. These include consignments from Askon Liberia General Trading Inc and Tropical Wood Group of Companies that ended up in India, according to one of the firms’ transactions.

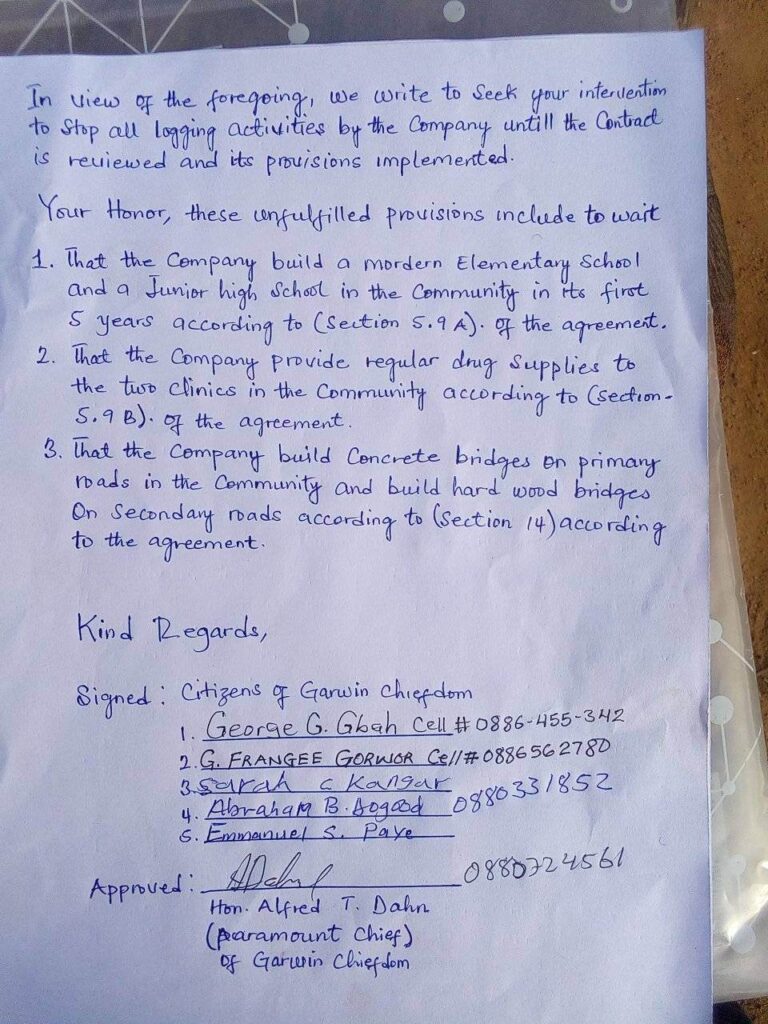

Villagers Play a Role

Villagers, too, play a role in the kpokolo trade.

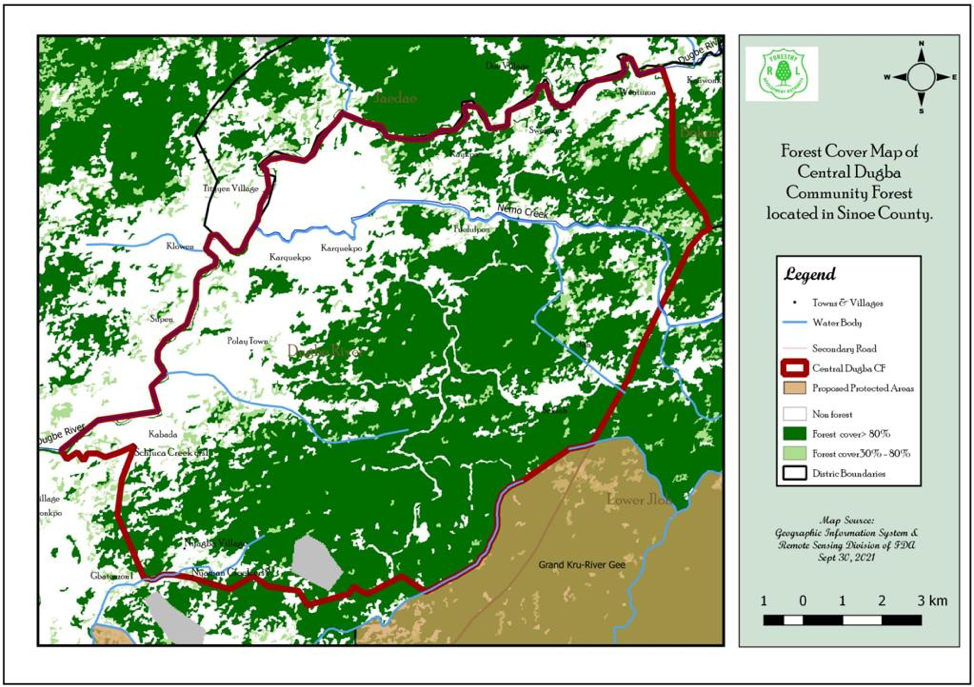

Villagers own the forest adjacent to their communities as per the Community Rights Law and the Land Rights Act. However, they must seek the authorization of the FDA before they engage in logging activities.

This is not the case, chiefs, elders and farmers get into deals with loggers, mostly verbal agreements, and allow them to harvest trees. In exchange, the loggers pay a fee and, in some instances, conduct projects, including roads and bridges. In Darmo’s Town, a community in the Bopolu District of Gbarpolu County, a kpokolo operator built a bridge.

Smugglers Collude with Officials

Kpokolo smugglers take advantage of the legal use of containers to transport logs, the lack of due diligence and coordination between the FDA and shipping authorities, and collusion between corrupt officials and smugglers have helped fueled the illegal trade.

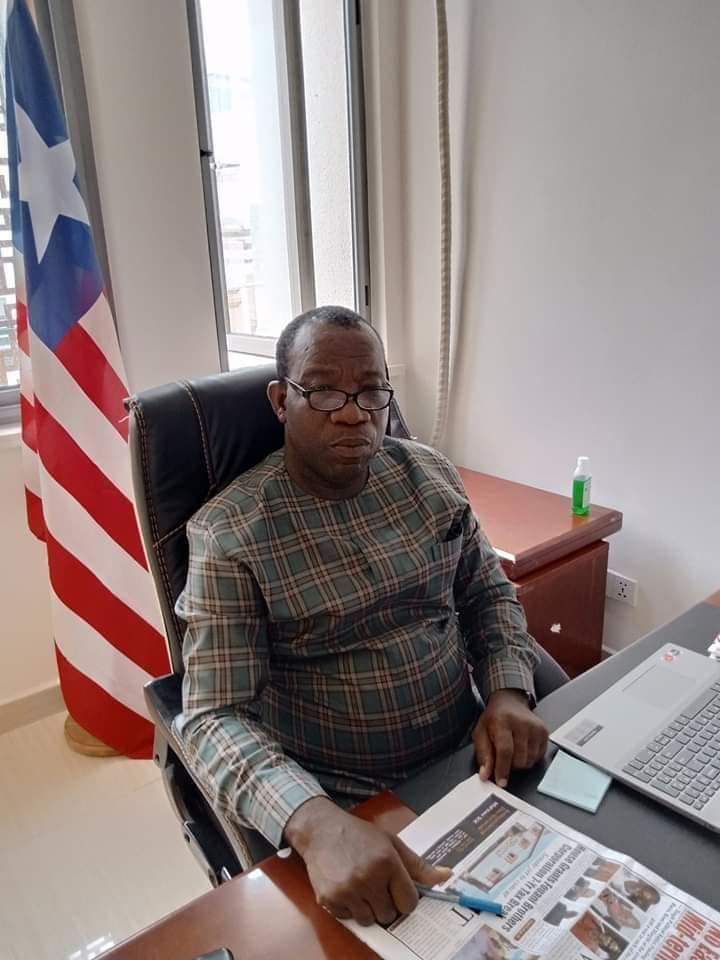

For instance, Assistant Minister for Trade Peter Somah aided Askon to smuggle at least two containers of timber to India in October 2020.

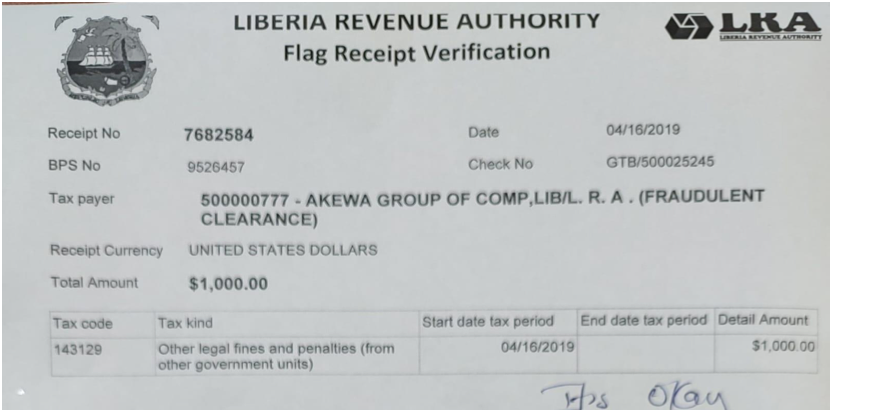

The FDA itself plays a part

The most noteworthy player in kpokolo trafficking is the Forestry Development Authority. The FDA awards certain permits to kpokolo operators outside the log-tracking procedure called the chain of custody system.

Back in March, Edward Kamara, FDA’s manager for forest product marketing and revenue forecast, announced that the agency has issued “tens of permits.”

The announcement had been coming for months. Announcing the unofficial ban on kpokolo in February, Kamara admitted that the FDA had awarded kpokolo loggers permits to trade locally. However, he said, “timber arrested for attempting to illegally export consisted of these dimensions. Therefore, it is the chainsaw milling block wood… that is banned to be brought to the market, especially in Monrovia.”

What Kamara did not say was that the permits the agency issued to kpokolo operators did not go through the chain of custody system and that the fees it collected did not go into government coffers. The same goes for funds related to the transportation of the wood. These are serious violations of the National Forestry Reform Law and the Regulation on the Establishment of a Chain of Custody System.

This story was produced by the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).