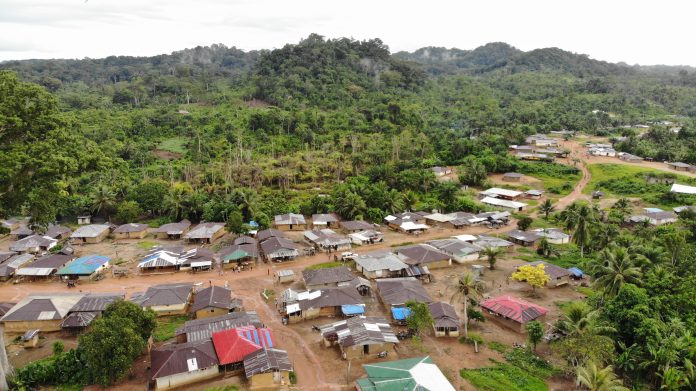

Top: Tartweh-Drapoh is one of several communities affected by Golden Veroleum Liberia’s palm plantation. The DayLight/James Giahyue

By Emmanuel Sherman

- Golden Veroleum Liberia (GVL) has failed to build a clinic for the Tartweh-Drapoh Chiefdom per a 2014 MoU, stemming from the company’s 2010 concession agreement with Liberia

- GVL’s failure to live up to the MoU led to a protest in May last year, with the company and people signing a resolution for a temporary clinic

- The temporary clinic was set up in October 2023 and interviews were conducted in April this year. Yet, the clinic has not started operations

TUBMANVILLE, Sinoe County – At the beginning of the last rainy season, the people of Tartweh-Drapoh Chiefdom staged a protest against Golden Veroleum Liberia (GVL). They prevented staff from going to work and stopped cars from plying local roads.

The protest followed several years of communications and negotiation between GVL and locals, over the former’s implementation of an MoU. Signed in 2014, the MoU obligates GVL to build roads, bridges, hand water pumps, schools and clinics. However, it did not live up to the document, prompting the protest.

“GVL does not like [roundtable] negotiation, they like violence,” said Nunu Broh, the chairman of the Tartweh-Drapoh Agriculture Committee, months before the strike. “GVL asked for our land and we gave it but now they are depriving us.”

Due to the intervention of the Liberian government, Broh and other locals called off the protest, with GVL signing a resolution to implement the MoU.

The new document called for GVL to establish a temporary clinic in Tartweh to cater to the communities, including GVL’s workers and dependents. But it would soon be another chapter in the GVL-Tartweh-Drapoh long story.

The document shows that over a year since the resolution the clinic has yet to open. It should have started within two weeks, in May. But four months now, the facility is yet to be opened.

Shortly after the resolution, GVL transformed one of its managers’ camp houses near Tubmanville into a temporary clinic. The company sought applications from residents and conducted interviews but has not shortlisted successful applicants.

Currently, sick residents have to walk two or three hours to Kadaba in the neighboring Mantron Chiefdom for treatment. The other option is at the government clinic in Tubmanville, Tartweh-Drapoh’s most populous community.

“We want a clinic for our people. We don’t have to go to different people’s camps to get treatment,” said Broh in a mobile phone interview.

GVL signed the MoU with Tartweh-Drapoh for its 7,000 hectares of land in exchange for development. GVL had signed a concession agreement with the Liberian government in 2010 covering 220,000 hectares in Sinoe, Grand Kru, Maryland River Gee and River Cess.

The largest oil palm investment, GVL is arguably the most notorious postwar company in Liberia. Its 14 years have witnessed a string of land grabs, human rights abuses, and a pattern of environmental pollution and degradation.

Alphonso Kofi, GVL spokesman, claimed the Tartweh-Drapoh MoU obligated the company to support an existing clinic where GVL did not build one.

“The temporary clinic is set up now and ready for operation,” Kofi said in an email.

“Staff were selected from [the] interview conducted by the county health authorities. These staff are currently being processed by the [human resource] department, while the opening of the clinic is set for September 2, 2024,” Kofi added.

Kofi wrongly referenced the MoU. The Document requires GVL to construct, equip and staff the clinic. The services to this clinic will be free of charge to employees and their dependents, it says.

Also, Kofi’s date for the opening of the temporary clinic has not been officially announced. Rev. Armstrong Panteene, the secretary of the Tartweh Agriculture Committee, said he was unaware of the assumed opening date. Odune Dunbar, a member of the committee, and Broh said the same. However, Broh said he received a text informing him of the 2nd September date.

Kofi’s false claim about the MoU adds to the company’s lies in a recent press release, claiming it investigated and took community complaints seriously. But a routine environmental audit report contradicted the company. The report called on GVL to address the lapse urgently.

Green Livelihoods Alliance provided funding for this story. The DayLight maintained editorial independence over the story’s content.