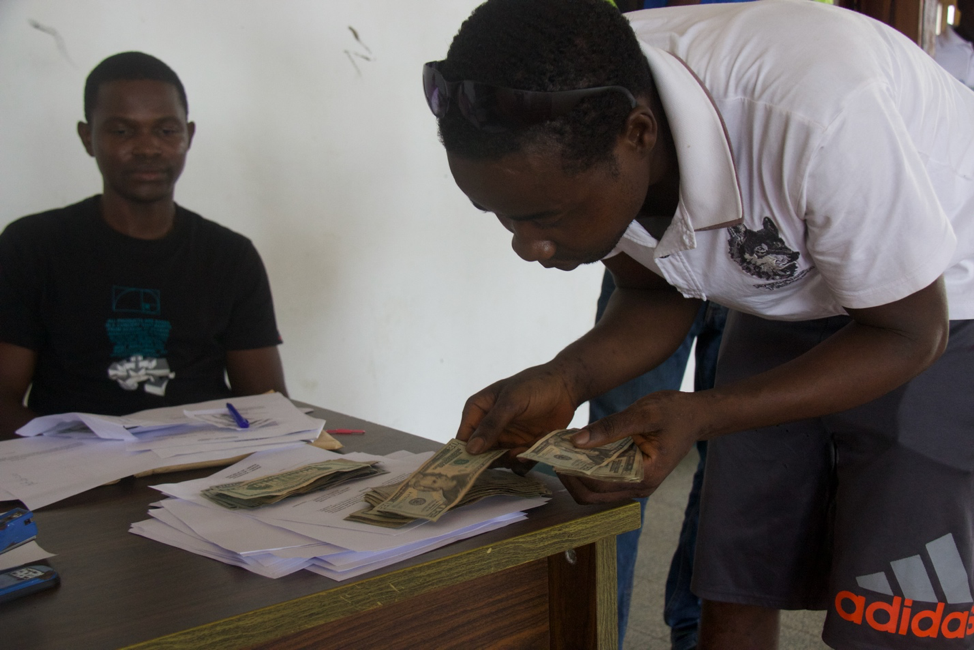

Top: Sand mining on the Robertsfield highway. The DayLight/Harry Browne

By Gabriel M. Dixon

MONROVIA – Since its establishment in 2009, Liberia Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative has provided information on the governance of extractive resources, and encouraged openness and sound management of Liberia’s natural resources and the revenues generated therefrom by the government. In June this year, LEITI released its 13th report to the public in keeping with its Act. The report covers mining, oil and gas, agriculture, and forestry.

It provides insights and depths into the activities and operations of companies in the extraction of minerals and logs, and the production and processing of rubber, oil palm, cocoa, and others.

Here, The DayLight highlights seven takeaways from the report you need to know:

Iron Ore Leads Export

Extractive resources remain the main export commodities for Liberia. The country is heavily dependent on its natural resources with mining the largest contributor. Between 2019 and 2020, Liberia exported iron ore, diamonds, gold, bauxite, and other base metals. It also exported rubber, cocoa, and round woods from the agriculture and forestry sectors.

ArcelorMittal was the sole producer of iron ore, with Europe being the main destination of the commodity. Iron ore represented 78.6 percent of the value of export in 2019-2020. Diamonds accounted for three percent of export value, with Israel the main destination of the precious minerals.

Mining Is Once More On Top Of Extractive Industries

Mining interjected the highest revenue from extractive activities in the domestic economy. It contributed US$45.243 million in the 2019/2020 fiscal year out of US$70.915 million in total revenue.

Minerals currently being mined in Liberia include iron ore, gold, diamonds, bauxite, and several base metals. Income from those minerals represents 63 percent of revenues generated from the entire extractive industry for the fiscal period the report covers. Second to mining was Agriculture which generated US$17.455 million, mostly from concession-related operations in the rubber and oil palm subsectors. Agriculture was followed by forestry, netting US$7.312 million primarily from logging operations.

Mining, agriculture, and forestry were the three highest performers in the extractive sectors in 2019/2020. Oil and gas also contributed to tax income despite low investment activities. It contributed US$0.905 million to the revenue stream of Liberia for the period.

Rubber was the largest export commodity in the agriculture sector. it represents 81 percent of the total value of commodities exported by agriculture companies in 2019/2020. The Liberia Agriculture Company (LAC) exported more rubber than any other company during the period, representing 56.7 percent of the total rubber exported.

Crude Palm Oil and Kernel were exported by two companies, LIBINCO Oil Palm and Golden Veroleum Liberia. Both companies exported US$27.063 Million value of crude palm and kernel oils in 2019/2020. Total tax income from agriculture for the period was US$17.455 million with Firestone contributing 36.2 percent of the amount.

ArcelorMittal Is Liberia’s Biggest Taxpayer

Mining giant ArcelorMittal again tops the list of taxpayers. The company paid US$30.966, making it the biggest contributor of tax dollars in the extractive sector. It exported 9.5 million metric tons of iron ore between 2019 to 2020 on which the company paid taxes to Liberia. Firestone Rubber Company, the largest agriculture company in Liberia, paid US$6.318 million in taxes, making it the second biggest taxpayer. The company occupies the biggest land concession area in the history of Liberia with 405,000 hectares of land. oil palm companies Golden Veroleum in Sinoe County, and Equatorial Palm Oil in Grand Bassa County came third and fourth, with tax remittances of US$2.254 million and US$0.773 million, respectively.

ArcelorMittal and three other companies accounted for 92.2 percent of total tax income generated from mining in 2020. The other companies are BEA Mountain Mining Company, MNG Gold Liberia, Inc., and Hummingbird Resources, Inc. Arcelor Mittal is the sole producer of iron ore while BEA Mountain, MNG Gold, and Hummingbird are all involved in the extraction of gold, according to the report.

Community Forests Exported More Logs Than Forest Concessions

There were more logging activities in community forest management areas (CFMA) than in forest management contracts (FMC) areas in Liberia, according to LEITI. Community forests produced 65,997.52 cubic meters or 75 percent of round logs in 2019-2020, while large-scale concessions produced 21,999.18 cubic meters of timbers. Total annual production for the period was 87,996.7 cubic meters according to information provided by the FDA to LEITI.

The export value of round logs was US$4,023,280, representing payments by 20 logging companies. The total volume of round logs exported was 230, 642 cubic meters with community forest exporting 54. 7 percent of the total volume while large-scale concessions and other forest agreements accounted for 48.3 percent.

Community Forest Management Agreements and Forest Management Contracts are the two main types of agreements that produce round logs for export. Asia was the main destination of Liberian woods with China accounting for 62.4 percent of export There were more logging activities in community forests than in large-scale forest concessions. Out of the 87,996.7 cubic meters of round logs that were produced.

Community forests exported 127,139 cubic meters of round logs or 55.1 percent of the total round wood production for the fiscal period of 230,654 cubic meters. The total value of round woods exported was US$4,023,280.

Community forests and large-scale concessions or forest management contracts are the two main types of agreements that produced round logs for export.

Agriculture Companies Employed More

The agriculture sector was the largest employer in the extractive industries. The sector workforce stands at 14,845, second only to the mining sector. Firestone remains the largest contributor to employment in the agriculture sector.

The sector is also the largest benefactor to social and environmental expenditure and it accounts for 68.5 percent of the total expenditure highlighted in both the agriculture and mining sectors. Total social expenditure by the agriculture sector was US$1.924 million in 2019 and 2020.

The International Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (IEITI), the parent oversight body of LEITI, defines Social and environmental expenditures as “a form of contributions from companies with the aim of supporting social development or to account for potential environmental impact.” In some cases, these social or environmental payments are based on legal or contractual obligations. In other cases, companies make voluntary social or environmental contributions.

LEITI agreed that based on the 2019 report, any public social expenditure such as payments for social services, public infrastructure, fuel subsidies, national debt servicing, etc. made by NOCAL i.e., outside of the national budgetary process be regarded as a quasi-fiscal expenditure

Companies Are Hiding Their Owners

The LEITI Act requires companies to disclose information on those who own them. but the institution found that many companies are not providing “ beneficial ownership” information as required by the Liberian Business Association Act of 1976 as amended in 2002.

The report said only 31 of the 132 companies that applied for or had licenses, were active in the mining sector. From the 31, only seven have declared who their owners are.

In the forestry sector, 28 companies but just three of them actually disclosed ownership. One company also provided partial owners’ identities. What it means is that 86 percent of companies engaged in logging in 2019/2020 did not disclose to government regulators who their owners are but were allowed to operate.

Similarly, in the agriculture sector, one company provided detailed information on the company ownership, and another company provided moderate ownership information to regulators from 13 active licenses issued in that period.

The Oil & Gas sector reported two active licenses issued to Chevron Liberia Holdings (Limited), and Deeco Oil & Gas. Chevron is a listed company on the international market. But Deeco Oil & Gas did not provide information on its owners.

Concealment of company beneficial ownership enables many illegal activities, such as tax evasion, corruption, money laundering, and financing of terrorism, to take place out of the view of law enforcement authorities. Governments and international financial and business regulators now require companies to declare shareholders or ownership information to the public as part of global transparency initiatives.

The Business Association ACT of 2002 empowers the Liberia Business Registry to implement beneficial ownership disclosures which enhance transparency in doing business. In 2021, Liberia signed up for the Opening Extractive Program (OEP). OEP is intended to assist Liberia to implement the beneficial ownership (BO) regime. Under the 2009 ACT of LEITI companies are required to disclose once every year the data on payments and other revenues.

Companies Are Not Providing Relevant Information

Section 7.2 of the LEITI Act mandates the institution to report on a regular basis, to the president of Liberia and the general public. Such a report should include payments and revenues, audits, and/or reviews of concessions and contracts between the government and companies in the extractive sector.

The report, however, said companies are not providing all of the information mandatory for full disclosure of contracts. It said it has “noticed that some mining contracts were not publicly disclosed on any of the agency’s (Ministry of Mines and Energy) platform” despite the companies being actively engaged in mining activities during the reporting period. It further stated that “While all mining licenses are being disclosed on a license portal, the terms and conditions associated with those licenses are not disclosed.”