Top: Quezp runs an illegal zircon sand mine in Brewerville, where it operates a plant. The DayLight/Charles Gbayor

By Charles Gbayor

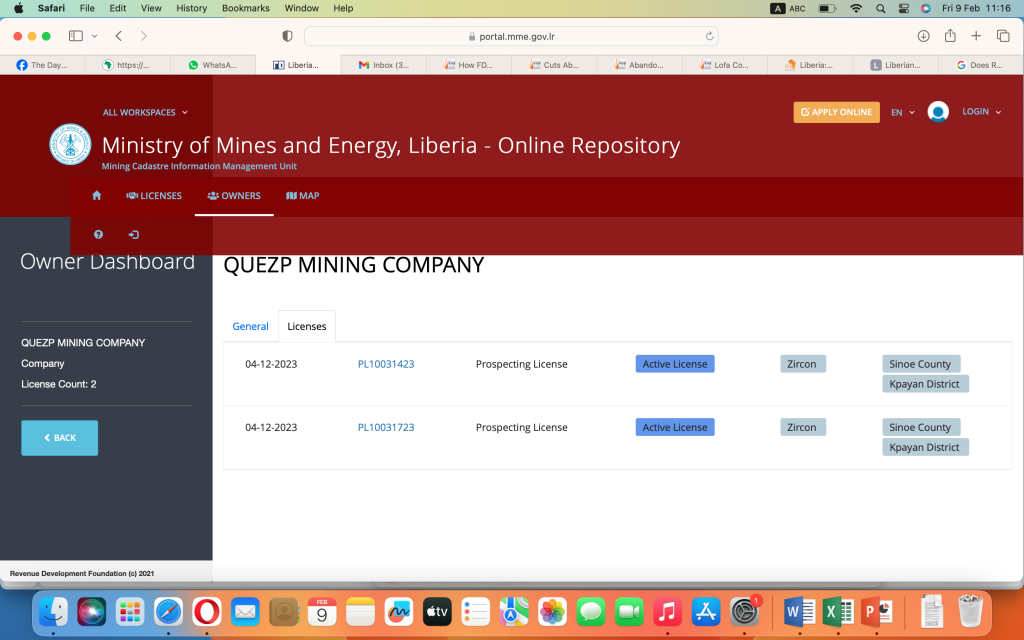

BREWERVILLE; ROYCEVILLE – Quezp Mining Company, a Liberian-owned firm, has a pair of licenses for mines in Sinoe County. However, it operates two illegal mines in suburban and rural Montserrado, according to an investigation by The DayLight.

Established in May 2022 by Terrance Collins, a Liberian businessman, Quezp acquired the two licenses to prospect for zircon sand in Kpanyan District, Sinoe, official records show.

But the company established two other operations in Brewerville and Royceville without any licenses. Official records show that it does not have any active licenses other than the ones in Sinoe. There are no records of a Quezp license being under review, surrendered, suspended, canceled, or expired.

Quezp has operated the illegal mines since February 2022, according to residents and people involved in the illicit operations. That was about three months before the company was established and more than a year before it obtained the licenses for Sinoe.

“I am here most often with my pickup for transportation business and I see them pass here with the sand most often,” said Saah Amara, a resident who transports building materials into Brewerville. “We want them to leave this place because they are not helping us at all.”

Mining without a license is an offense under the Minerals and Mining Law. Violators face a fine of up to US$2,000 and a 24-month maximum prison term, or both fine and imprisonment if convicted by a court.

‘We mine black sand’

Quezp conducts the two operations as one. The company buys zircon sand from Royceville and transports the mineral to its mine and processing plant in Brewerville.

Fifteen minutes from the VOA Junction, the Brewerville site is nearly surrounded by a huge, green mangrove and palm forest. It is several yards away from the ocean.

Denied access to the site, The DayLight used a drone to sight the mine. The elevated view showed the royal blue plant enveloped by giant-sized piles of zircon sands. A forklift loaded a truck with 25-kilogram bags filled with the mineral, used in the ceramics industry. China and Australia are the biggest importers of zircon sand, with Africa an emerging market. Global trade is estimated to reach US$3.69 billion by 2029.

Representatives of Quezp purchase zircon sand from residents in the rural Montserrado area for up to US$75 for a truckload, the residents said.

Gus Doe Howe, Sr., a trucker who lives in that region, commonly called Tony, transfers the sand to a particular location.

Afterward, the company transports it to Brewerville, processes and prepares the mineral for export, the residents said.

“I am a fisherman but I also do black sand mining for daily survival. The sand we mined has been sold at US$20 for a pickup load and US$75 for a truckload,” Jacob Jackson, a Royceville resident told The DayLight in an interview at the mining site.

“We mine black sand here and one guy named Tony comes here daily with his pickup to buy it and transport it,” Justine Gayflor another RoyceVille resident. Black sand is the local name for zircon sand.

The DayLight photographed about a dozen mounts of sand in an array on a Royceville beach. Large holes lined up nearby as the ocean gradually reclaimed the disturbed shoreline.

Tony confirmed his involvement in the illegal activities in a phone interview. He had left the area four hours earlier when The DayLight arrived there, residents said. Tony, however, denied buying the mineral on behalf of Quezp.

“I, just go there with my pickup to transport the sand for them from the mining site and I take it to a point where the guys who buy from the company can get it,” Tony said.

Collins, Quezp’s owner, is linked to other companies—Wayful Mining Company Limited, Hauli Company Liberia Limited and Glorious Mining Company, to name some. They hold some of the 52 zircon sand licenses the Ministry of Mines and Energy issued from 2012 to last year, the records show.

Collins declined an interview with The DayLight.

[This version of the story corrects an earlier version that spelled Royesville “Royceville.”]

Funding for this story was provided by the United States Embassy in Monrovia. The DayLight maintained editorial independence over the story’s content.

Facebook Comments