Top: Terrence Collins, also known as Terrentius Tidiboh Collins, is one of four suspected timber smugglers. Picture credit: LinkedIn/Terrentius Collins

By James Harding Giahyue

GBARNGA – The Forestry Development Authority (FDA) is seeking penalties for four suspected timber smugglers who operated at the Central Agriculture Research Institute (CARI) in a lawsuit at the Ninth Judicial Circuit Court in Gbarnga, Bong County. The court has seized thousands of timber abandoned at the facility and impounded the machines the suspects used.

FDA petitioned the Ninth Judicial Circuit Court in Gbarnga, Bong County to imprison two Chinese nationals Chaolong Zang and Guoping Zang, a Turkish man Mehmet Onder Erem, and their Liberian alleged accomplice Terrence Collins. The agency seeks a 12-month term for the men if convicted, court documents filed this and last month show.

The lawsuit seeks a US$25,000 fine for the men as well as a forfeiture of machines and a vehicle used in their operations.

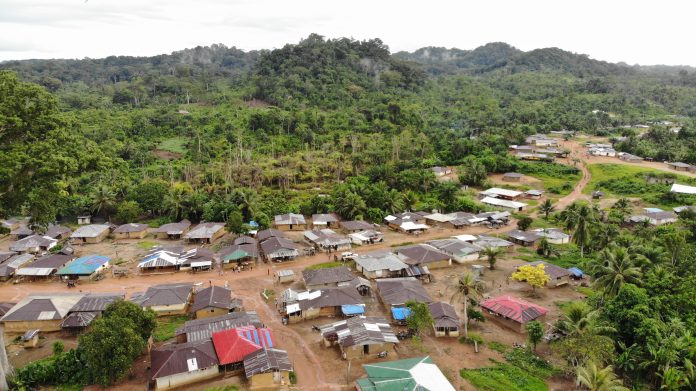

It accuses the men of conspiring and disregarding the law to “engage in logging activities, including the illegal harvesting, purchasing, transporting and processing of timber…” It adds that they “established a mini sawmill on the premises of… CARI…, where timber was being processed and smuggled out of Liberia…”

The lawsuit also seeks the forfeiture of a vehicle recently used by the suspects to transfer some of the timber to another location. Police in Gbarnga had arrested Jonah Jackson, the driver of one of the suspects, for transferring the wood to his house in Suakoko, police records show.

“On Wednesday, July 17, 2024, Mr. Zang sent me for the wood to take it from the CARI compound and carry it to my place in Suakoko for safekeeping,” Jackson wrote in a police affidavit.

“On Sunday, July 21, 2024, we continued to haul the balance. But surprisingly, while we got on the compound, we saw the CARI security and the OIC, and they called the police to arrest us.”

The court has impounded all machines and vehicles and imposed a stay on the timber until it determines the FDA’s petition. If granted, it will be the first time the agency has enforced the Regulation on Confiscated Logs, Timber and Timber Products since it was formulated in 2017. Previous attempts in Bomi, Gbarpolu and Monrovia in 2022 proved futile.

The lawsuit comes barely a month after the FDA abruptly aborted an initial attempt to petition the court. An April investigation by The DayLight had exposed the suspected syndicate, showing photographs and documents of the allegedly illegal operation.

Board Resolution

The men deny any wrongdoing, saying they would not have exported the timber without the FDA’s approval. They are asking Judge Cornelius Wennah to dismiss the case for “lack of legal capacity to sue” them.

Their lawyer Nathaniel K. Innis, Sr. argued that two prosecution resolutions by the board of directors of the FDA had expired. One of the resolutions, signed in 2022, calls on the FDA to prosecute alleged forestry offenders. The other, signed in 2017, endorsed the confiscation regulation being used in the trial.

“It behooves the current Managing Director Hon. J. Rudolph Merab, Sr. to have filed a petition against the [four men] with a board resolution…,” the petition read.

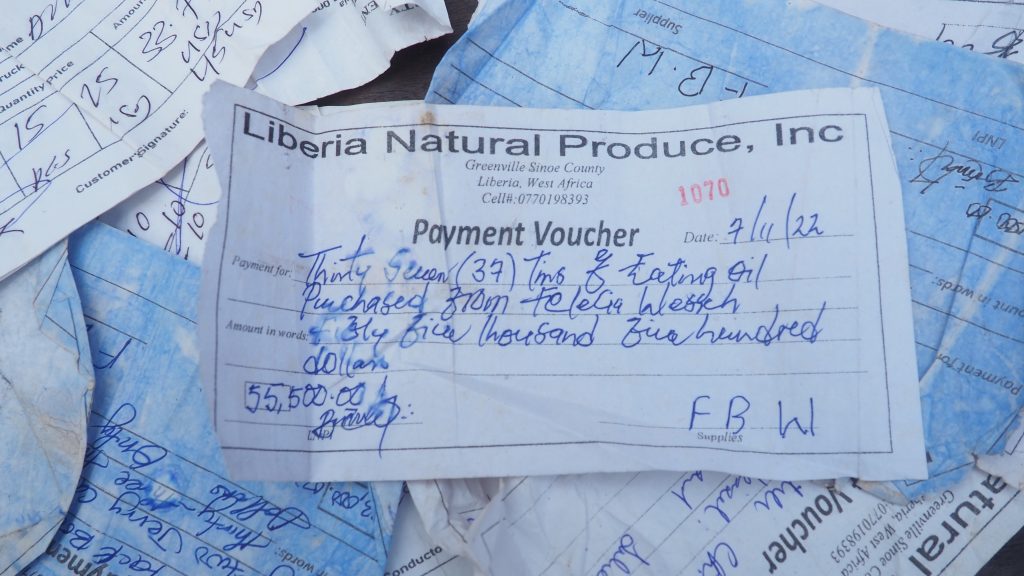

Innis also argued that the suspects legally purchased logs from Alpha Logging and Wood Processing Company, which abandoned its concession in Lofa and Gbarpolu Counties. Therefore, Innis further argues, that the men could not forfeit the vehicles or machines and that the FDA had no right to confiscate the wood in question.

In Innis’ motion for dismissal, FDA lawyer Cllr. Yanquoi Dolo counterargued that it has the authority to enforce forestry legal frameworks and that the board resolution, which Innis hinged his argument, was a matter of corporate governance. Dolo argued the 2022 resolution was still valid and should be used to prosecute the suspects.

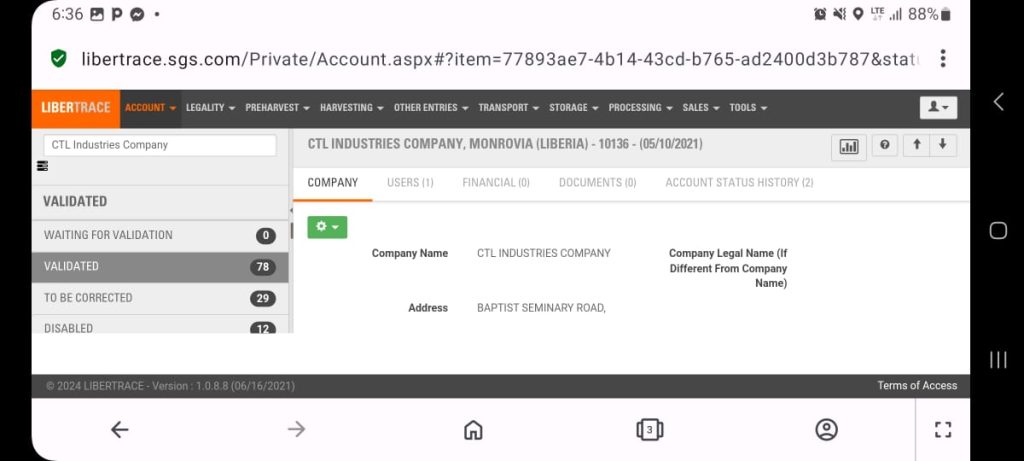

Dolo further argued that the men’s operations were illegal as the FDA did not permit them. He added that their transactions with Alpha Logging were not recorded in the FDA’s timber-tracking system.

The next hearing of the case has not been scheduled.

[Additional reporting by a Bong-based journalist]

This was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).