Top: An elevated view of an oil palm mill at a plantation Equatorial Palm Oil (EPO) abandoned five years ago. The DayLight/Derick Snyder

By James Harding Giahyue, Derick Snyder and Varney Kamara

- In August 2022, Liberia Natural Produce Incorporated (LNPI) purchased an abandoned palm plantation from Equatorial Palm Oil (EPO) in a deal worth approximately US$445,000

- Publicity of the deal was scanty, limited to a LinkedIn post, a reference on LNPI’s website and an announcement hidden in EPO’s parent company’s annual reports.

- The Liberian government has not approved of the takeover, with the Ministry of Agriculture and the lawmaker of that district unaware of the deal.

- Yet, LNPI is forcibly operating the plantation, including a prewar oil palm mill. With the help of armed police officers, the company is throwing residents out of the plantation.

- The company disregards local communities’ ownership of the land and their right to consent to the takeover.

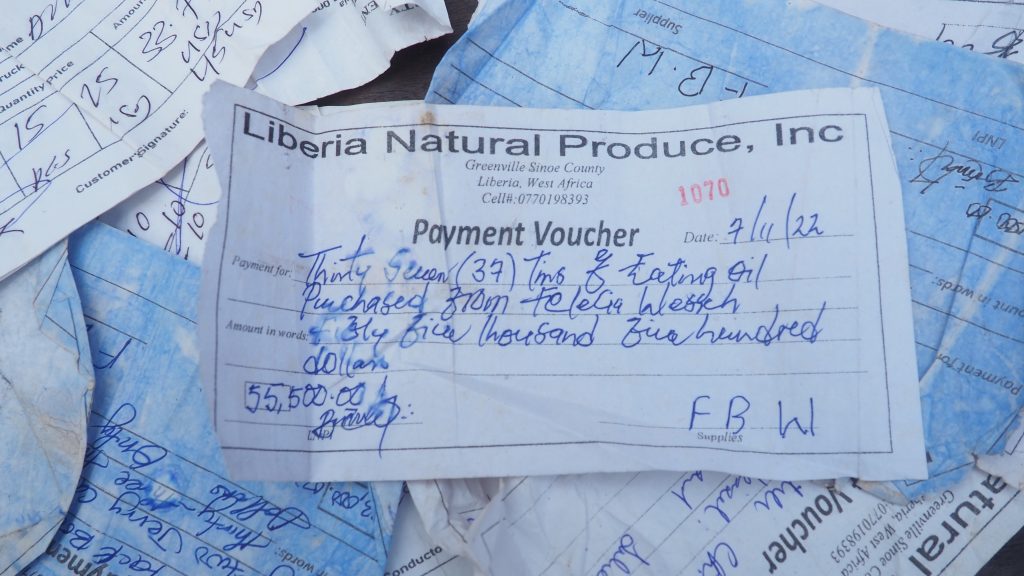

SHAMPAY CAMP, Sinoe County – In June, armed police officers ordered Felecia Wesseh and other villagers to leave an abandoned palm plantation. A company called the Liberia Natural Produce Incorporated (LNPI) told the residents they were taking over a portion of the 8,000-hectare plantation from Equatorial Palm Oil (EPO), which had run it in 2019. Wesseh and other residents exploited the plantation and transformed the region into an artisanal palm oil hub ever since.

“I feel bad because number one, for me, this is my 25 years in this area. “The way the Emergency Response Unit [of the Liberia National Police] is coming here to take people from this place is not good,” said Wesseh, a mother in her late 30s. The DayLight interviewed her at her shop in Sankwehn Estate in Tarsue Chiefdom, Sanquin District locals have called Shampay Camp since the 1960s. A crowd of angry residents quickly gathered, questioning the legality of the takeover.

“By right, if you own the plantation or buy the area, I expect the Superintendent… to come with one of the lawmakers to show the people to us. Nobody brought them to show them to us,” Wesseh added.

Wesseh was right. There is evidence that LNPI bought the plantation from EPO. However, no one in the Sanquin District is aware of the takeover, and it has not been approved by the Liberian government.

In August 2022, Kuala Lumpur Kepong Berhad (KLK) of Malaysia, EPO’s owner, sold the plantation to Konnex Investments Limited, the parent company of LNPI, for approximately US$445,000, according to KLK’s annual report for that year. Uday Pilani, Konnex’s owner posted the deal on LinkedIn and LNPI mentioned it on its website a month earlier.

EPO owned the plantation through its subsidiary Liberia Forest Product Incorporated (LFPI). LFPI signed the concession with the Liberian government in 2008 for 50 years, covering 8,400 hectares. However, in 2019, EPO ceased operations because there “were insufficient plantable areas,” making it “uneconomic” to run. It devalued the plantation by RM145.3 million (approximately US$32.2 million).

But the deal was not entirely transparent. KLK, required to declare such transactions under Bursa Malaysia or the Malaysian stock exchange rules, announced the takeover in its 2022 annual report. However, there is no record that EPO—under a similar obligation with the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) of the London Stock Exchange—publicized the takeover. This likely breaches AIM’s rule, which mandates companies to publish such transactions. EPO did not return questions for comments regarding the takeover and KLK said it would respond.

‘Into a hole’

The Shampay Camp part of the story began on August 23, 2022, when LNPI signed a six-month memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the people of Sanquin District. Per the MoU, LNPI bought a five-gallon tin of palm oil for L$1,300 and L$1,500. LNPI paid the community US$6,000 and paved a major road there.

Local palm oil dealers had welcomed the agreement as LNPI prices more than double the L$600 artisanal palm oil producers had set, while chiefs and elders saw it as an opportunity for development.

“When they came, it was correct because they paid our royalties,” recalled Alfred Pyne, an elder of Sanquin.

But the MoU was too attractive to be true. While the community was entitled to several benefits, the MoU restricted LNPI to “purchasing of oil palm products such as crude palm oil, palm kernels and other palm derivatives,” and to operate “without any embarrassment and undue restrictions.”

LNPI’s true intent surfaced when it unilaterally extended the deal by three months. Following a year of anger, the parties met in January this year when LNPI finally disclosed it had taken over the plantation. The company was not merely a party to an MoU; it was claiming possession of Shampay Camp.

“When we saw Baccus Wiah with LNPI, I said, ‘A good thing is coming,’ not knowing we [were] getting into a hole,” said Eric Gbayon, the Township Commissioner of Tarsue Chiefdom. He was referencing LNPI’s administrative manager, who hails from that region.

In the end, the MoU was a disguise. By August 2022, LNPI had already signed the takeover, a negotiation it had started six months earlier, according to a document obtained by The DayLight. It had imported 117 consignments of electrical equipment and other instruments as of the 17th of last month. They were imported from India, Pilani’s home country, according to Volza, a Russian online marketplace, citing international data.

The DayLight videotaped workers test the mill, which has a capacity of five metric tons of crude palm oil per hour. For the first time since the start of the First Liberian Civil War in 1989, smoke billowed from the facility’s chambers into the gloomy Shampay Camp skies.

Before it disclosed the takeover to the people, LNPI had obtained an environmental permit from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) after conducting an environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) between February and May last year. It has asked for a renewal of the permit to extend the mill.

‘Not heard from them’

Tension has been brewing in Tarsue, particularly after the news of the takeover broke. After LNPI broke the news, locals asked to meet the company in Kommanah Town. LNPI instead requested to host the meeting at its headquarters in Shampay Camp, citing “continued threats of violence” from the community.

“If you are interested in meeting with me, please let me know so a time can be set that will be mutually convenient for both parties,” LNPI’s executive officer John Collie penned Paramount Chief John Koah a reply, seen by The DayLight.

Months later, locals lodged a complaint with Representative Alex Noah of Sinoe County District Three over LNPI’s illegal activities. In their letter, they listed the company’s takeover of the plantation and renovation of the mill without their consent. “We need our timely intervention concerning this matter before things go out of hand,” the letter read. Noah said he was unaware of LNPI’s operations and would visit the plantation when he returned from his travels out of the country.

LNPI’s disregard for the community’s right to consent violates the Land Rights Act, which recognizes ancestral land rights. Locals’ consent is a crucial principle of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), the watchdog of the global oil palm industry. Liberia has even domesticated the RSPO’s principles and criteria.

The Liberia Land Authority (LLA), which plays a role in land-related concessions, had recommended that LNPI get the locals’ consent but the company ignored the advice. LNPI had visited the LLA in Monrovia to seek counsel.

LLA’s Chairman Adams Manobah told The DayLight in a WhatsApp interview he had advised the community to first “formalize its land ownership before transacting business with an outsider or any investor.”

Manobah added, “Since that encounter, I have not heard of them.” Wiah did not respond to emailed questions on that conversation.

In an earlier interview at the company’s headquarters, Wiah justified LNPI’s use of force. “Due to the violence that took place here, since we have completed the factory and are ready for operation, we decided to bring [armed police officers] to be here to serve as [a] deterrent,” he said. “Our people are afraid of gunmen.”

Wiah admitted the government had not approved the LNPI’s takeover. An ex-EPO employee, however, Wiah claimed the approval was being processed. “The Ministries of Justice, and Agriculture have signed,” he told The DayLight. It is left with the Ministry of Finance, then it will go to the Senate, and finally to the President for signature.”

The Ministry of Agriculture dismisses Wiah’s claim. “It is important that we address this lack of awareness immediately,” Comfort Whitfield of the ministry’s communication division said in an email.

Editor’s Note: This is the first of a two-part series on illegal oil palm operations in the Sanquin District, Sinoe County. The second part will focus on the legality of the existence of Liberia Natural Produce Incorporated and its parent company Konnex Investments Ltd.

Facebook Comments