Top: A drone shot of logs in a log yard just outside Greenville, Sinoe County. The DayLight/Derick Snyder

By Eric Opa Doue and James Harding Giahyue

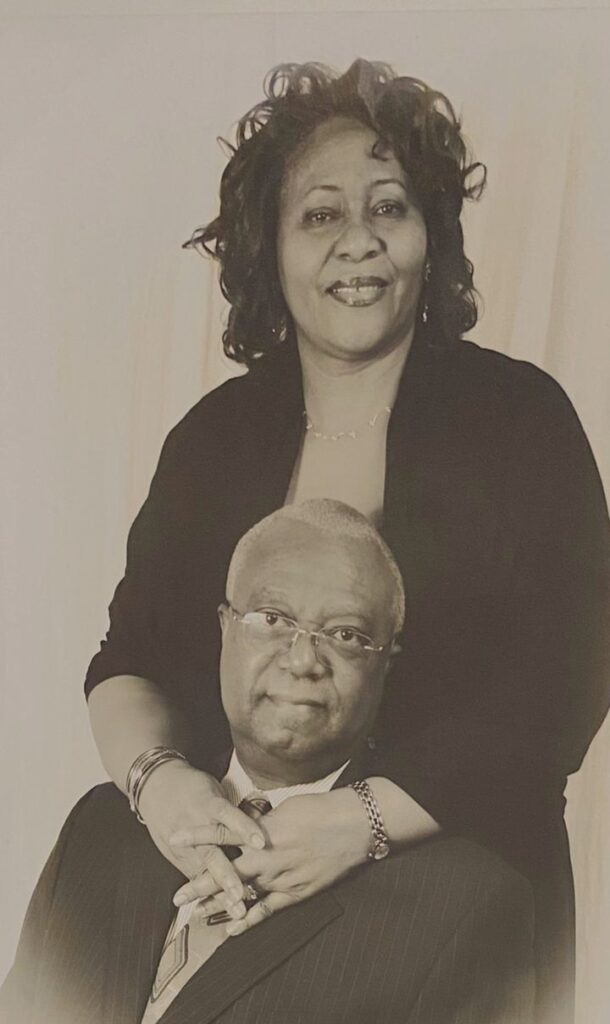

- Deputy Foreign Minister for Administration Thelma Comfort Duncan Sawyer controls Tetra Enterprise, a logging company operating in a community forest in River Cess County. That is according to documents The DayLight obtained, and her lawyer

- That violates the Liberian laws, including the Constitution, the Code of Conduct for Public Officials and the National Forestry Reform Law

- Sawyer could well be the owner of the Tetra. Her lawyer claims her family established Tetra as a “fallback position.” The company is legally owned by a woman named Annabel Morris. However, Tetra has a bearer share that is held by an unregistered individual

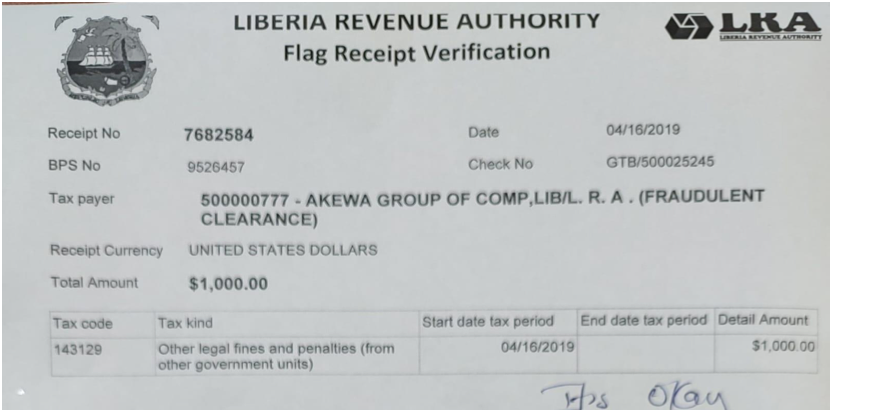

- Liberia’s Business Association Law prohibits bearer shares, which means the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) has illegally approved Tetra’s operations

- The company in question owes communities affected by its operation, failed to live up to its agreement with villagers and has abandoned a huge volume of logs

GOZOHN, River Cess – In October 2020, President George Weah appointed Thelma Comfort Duncan Sawyer, the manager/proprietor of Tetra Enterprise Inc., a logging company, as the Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister for Administration. Eight months later in June 2021, the Liberian Senate confirmed her.

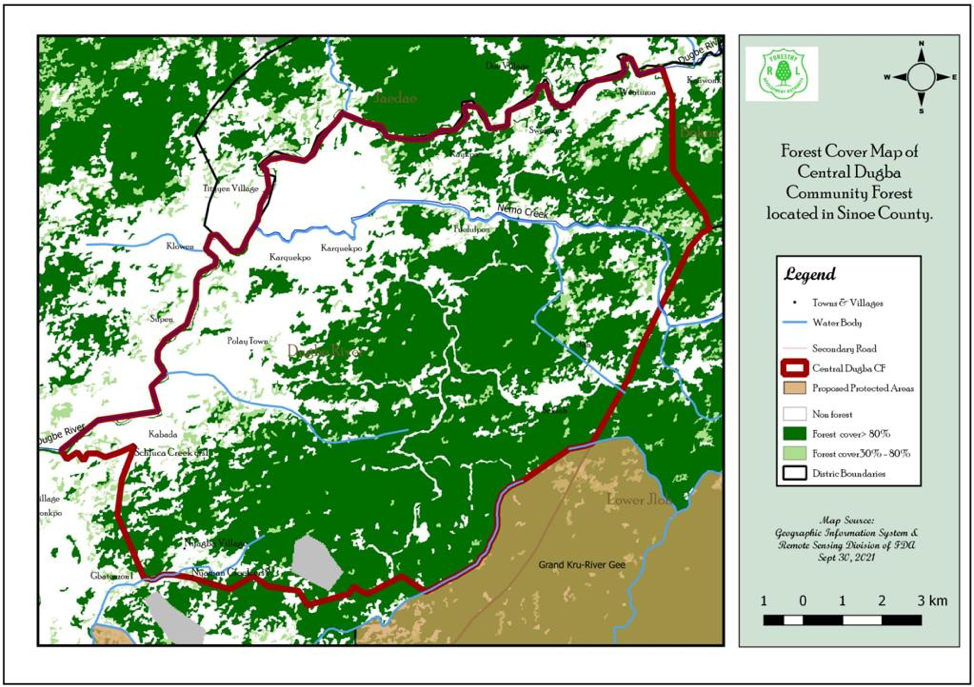

But even after assuming office, Sawyer has continued to run Tetra Enterprise’s operations in the Garwin Community Forest of River Cess County’s Morweh District, communications between Sawyer and the community forest’s leadership show. The letters discussed managerial issues: a new agreement, delayed payments, abandoned logs, and failed projects Tetra had promised in their March 2017 agreement for the 36,637-hectare forest.

“On behalf of the community and my family, we [wholeheartedly] welcome you back to Liberia,” read one letter Rev. Benison Sackor, the head of the Garwin Community Forest’s leadership, wrote to Sawyer on November 16 last year.

“Things have been so tied in your absence. We are pleased that you are here,” it added. Frank Nimmo, the chairman of Tetra’s board of directors, replied to Sackor’s letter on Sawyer’s behalf eight days after.

In an interview with The DayLight, Sackor said he addressed every communication for Tetra directly to Sawyer, who “instructs” it what to do. His comments were corroborated by other members of Garwin’s leadership, including Rev. Harry Gueh, the head of its executive committee, the highest decision-making body. William Yeasay, the public relation officer of Tetra, confirmed Sawyer took major decisions for the company.

Running a company while holding a government position contravenes a number of Liberian laws. The National Forest Reform Law debars members of the cabinet from conducting commercial forestry activities. Violators of the law face a fine between US$10,000 and US$25,000, up to three times the sum they received from their companies or a prison term of up to 12 months. Sawyer’s relationship with Tetra is a conflict of interest, a breach of the Liberian Constitution and the Code of Conduct for Public Officials. Penalties for this breach include a suspension or a dismissal.

“[A conflict of interest] hurts a country or any organization because the person having a such conflict of interest is likely not to be objective, but to put [their] personal connection or interest above the collective,” said one lawyer, who asked not to be named.

Sawyer, who has a faculty lounge named after her at a college at the University of Liberia honoring Dr. Amos Sawyer, her late husband, has a history of alleged dishonesty with Garwin. Sawyer had lost a bid to acquire the forest in 2016 Xylopia Incorporated, a company with her registered shares. A 2016 media report and a 2018 Global Witness report alleged she bribed and coerced villagers to sign a deal at the time. The media report by Mongabay alleged Xylopia paid villagers US$150, alcohol and rice for the villagers’ signatures.

In forestry, villagers own adjacent forests and have a right to co-manage them with the Forestry Development Authority (FDA). Illegally, Sawyer’s Xylopia had signed a memorandum of understanding with Garwin even before it legalized that right. The parties agreed that “It is clearly understood that no third party will come between the people of Garwin and Xylopia… It is also understood that Xylopia is the only company that will work with the people of Garwin.” The FDA terminated the deal following a protest. Global Witness used the incident to highlight how businesspeople were undermining community forestry, which was created to benefit locals.

Eventually, Tetra, co-owned by a Liberian woman named Annabel Morris, won the bid for the forest, with harvestable trees covering 96 percent of it. The Global Witness report also alleged Tetra, backed by county authorities, bribed villagers to seal the deal.

‘Fallback Position’

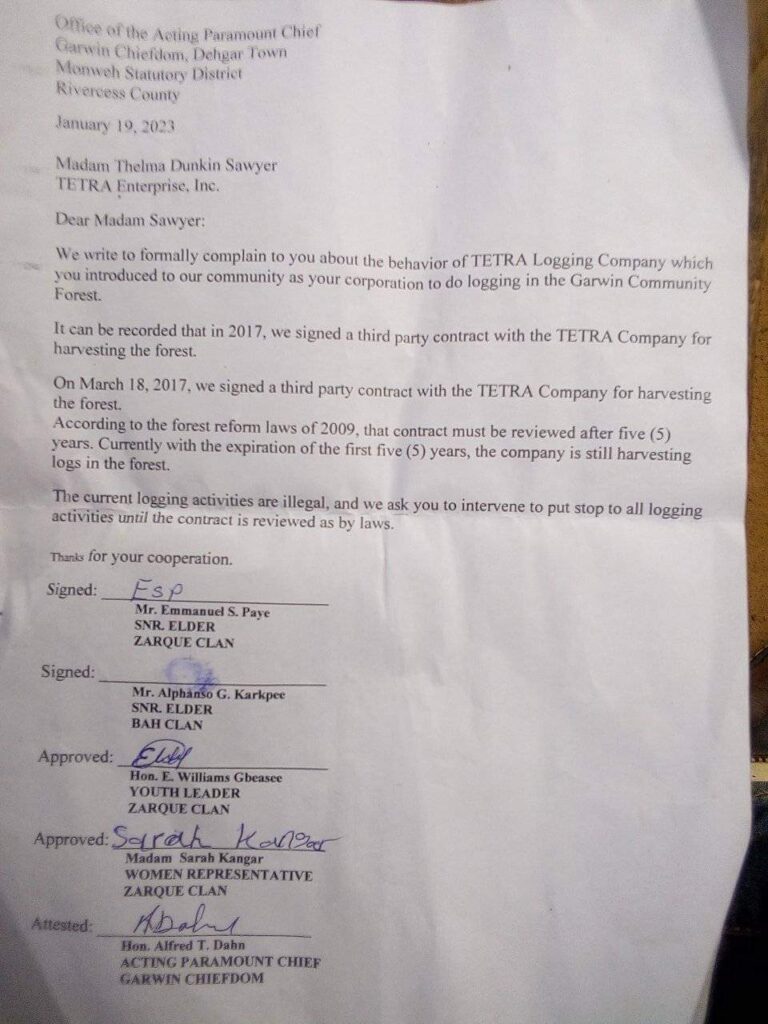

It was unclear how Sawyer ended up at Tetra but there are indications the widow of the fallen Chairman of the Governance Commission co-owns it. The Global Witness report cited unnamed villagers who claimed Tetra was the same as Xylopia. The DayLight obtained two January letters from the Office of the Acting Paramount Chief of Garwin Chiefdom that provide some clues. One of the letters addressed Sawyer and the other Senator Wellington Geevon Smith.

“We write to formally complain to you about the behavior of Tetra, a Logging Company which you introduced to our community as your corporation…,” the letter that addressed Sawyer read. The other one to Smith also restates Thelma Sawyer had allegedly brought the company “to harvest Garwin Community Forest.” Smith did not pick up our call.

Stephen Kai, Thelma Sawyer’s lawyer, claimed that the Sawyer family had created the company as a familial contingency project. “The old man (Dr. Amos Sawyer) decided to establish something as [a] fallback position whenever he [reached] the age of retirement,” Kai said. “[Thelma Sawyer] was doing nothing, so her husband decided, ‘Look you have to do something to see how we can generate extra incomes.’”

Tetra’s Secret Shareholder

Tetra’s shadowy ownership apparently supports Kai’s claims. Morris holds 51 percent of the company’s shares, 19 percent are reserved and 30 percent are bearer shares, according to the company’s article of incorporation. Bearer shares are shares whose holders are not registered or named. Firms pay dividends to the holders of the bearer shares based on an arrangement between the company and the bearer shares holder.

Kai may have simplified Tetra’s complex, shady ownership but he contradicts other facts about the firm. Thelma Sawyer already had Xylopia when Tetra was established, suggesting the Sawyers may have created the latter firm to get Garwin, not generally for extra income as Kai puts it.

But Tetra’s bearer shares make it ineligible for forestry activities in the country, anyways. The Business Association Law as amended in 2020 prohibits bearer shares in Liberia. It compelled firms in the country to convert such shares into registered shares as of December 31, 2020. The change in the law was part of a global effort to abolish bearer shares, which can lead to terrorist financing and tax evasion. It reinforces the reform agenda of Liberian forestry, which debars certain individuals from commercial logging, including human rights violators, embezzlers and fraudsters. It also renders the FDA’s approval of the company’s operations in the last two years and today illegal.

Kai did not comment on the bearer share issue. He, however, said Sawyer had stepped aside and the “day-to-day activities of the company are now being handled by her sister-in-law Esther Sawyer, sister to the late Dr. Amos Sawyer.” He added Nimmo, another relative, had been appointed as the chairman of the company’s board of directors to avoid a conflict of interest.

“We advised her as lawyers and she in fact said to us, ‘Look, any communication or any contact, you deal with… Esther.’ And so that we are aware of. But [did she communicate] that to all the stakeholders? No, I can’t say that,” Kai added. Efforts to get comments from Esther Sawyer and Morris—Tetra’s general manager in 2018, according to FDA records—were unsuccessful.

The involvement of Esther Sawyer and Nimmo with Tetra still remains a violation of the forestry law. Individuals who companies-linked officials have control over are barred from commercial logging activities, too. The law requires government officials to transfer their shares or roles in a company to a blind trust or someone outside their control, not relatives. A blind trust is a firm that manages’ people’s businesses to avoid conflicts of interest.

The FDA again broke the law and the Regulation on Bidders Qualification to authorize Tetra’s operations with the Sawyers’ relatives. The regulation requires to disapprove of logging contracts connected with government officials—or their relatives.

Thelma Sawyer or her relatives aside, the FDA would have broken the regulation if Thelma Sawyer is actually one of Tetra’s owners. Though bearer shares were legal in Liberia in 2017 when Tetra was created, the regulation mandates the FDA to get a full list of companies shareholders. Then the agency can tell whether or not the companies’ owners are on its debarment list.

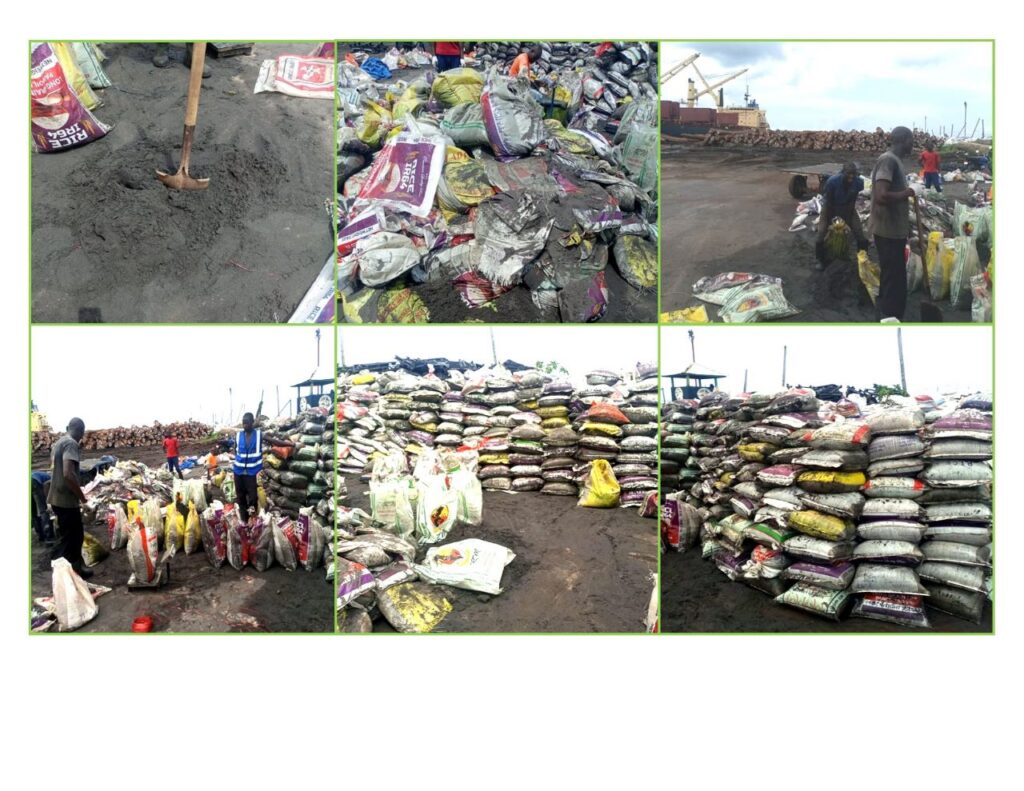

In 2021, the FDA approved Tetra’s harvesting plan amid conflicts between a map of the plan and another plan for its entire five-year operations in Garwin, according to a report by SGS, a Swiss firm that co-manages Liberia’s log-tracking system. Interestingly, Tetra harvested 4,264 that year it would abandon based on FDA records. The FDA did not respond to emailed questions for comments on this story.

Unfulfilled Promises and Abandoned Logs

Tetra’s bearer shares and links to Thelma Sawyer do not conclude the company’s illegalities.

Tetra has abandoned a large volume of logs. Between 2018 and 2021, Tetra harvested 46,729 cubic meters of logs and only exported just 18,690 cubic meters, according to the Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (LEITI). Thus, it abandoned 28,039.6 cubic meters of logs, based on The DayLight’s analysis of the LEITI records. It owed US$70,574.93 as of March 31, last year relating to its operations, minutes of a high-profile meeting of forestry actors at the time show.

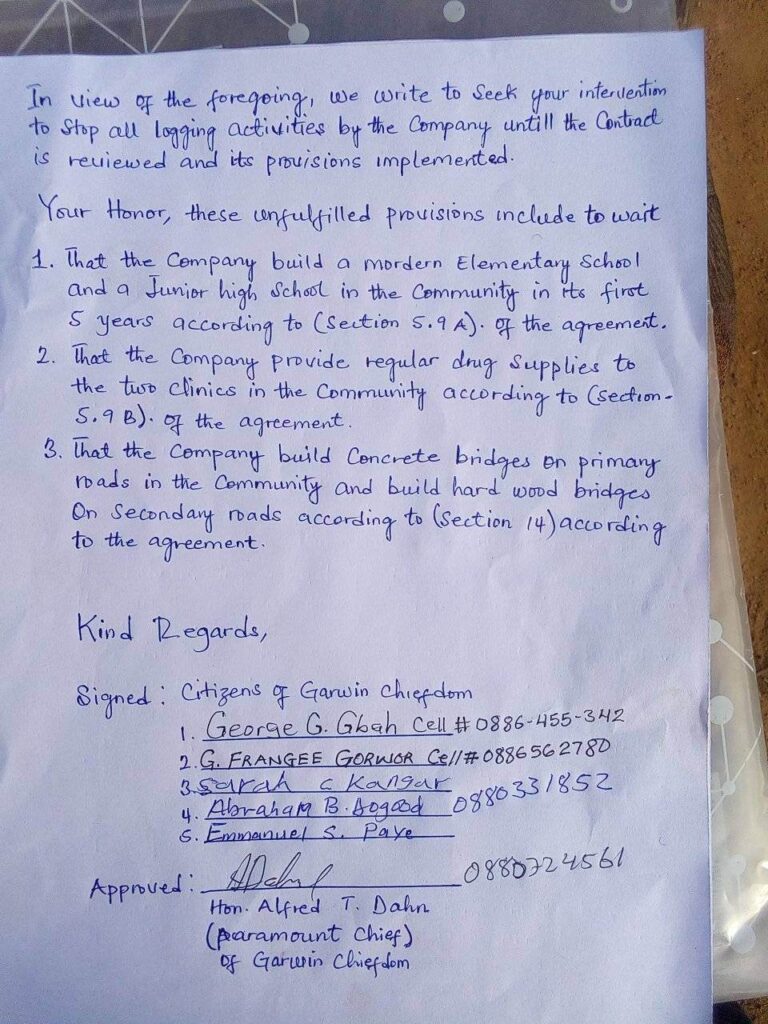

Tetra has begun work in Garwin in the absence of a new agreement. That is against the Community Rights Law of 2009 with Respect to Forest Lands that created community forestry. The law calls for companies to review their agreements with communities every five years before felling any other trees.

Tetra has not lived up to its agreement with Garwin. As per the agreement, Tetra should have constructed 18 handpumps in Garwin’s 15 towns and villages within its five years of operations. It only constructed two, according to locals. It also failed to build a school in the area, supply drugs to community clinics and build bridges.

Chiefs and elders have lodged a complaint with the Moweh Magisterial Court. “Six years have gone and the company failed to implement the provisions of the contract,” the April 7 complaint read. “We write to seek your intervention to stop all logging activities by the company until the contract is reviewed.”

The Story was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).