Top: The headquarters of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on Tubman Boulevard in Sinkor. The DayLight/Mark B. Newa

By Mark B. Newa

- The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) lied by suggesting The DayLight did not contact it for the online newspaper’s story over a spillage of chemicals from a Bea Mountain Mining Corporation (BMMC) in a river in Grand Cape Mount County more than two months ago

- The DayLight had actually contacted the EPA four days before its publication on April 19, accusing the EPA of concealing the pollution, Bea Mountain’s second in two years

- An analysis of EPA’s website shows EPA published the report on the spillage on April 5, 2023, more than a month after the incident. There was no press statement as done in the past. The general public remained unaware of the pollution until The DayLight’s report

- But publishing the report only on its website apparently breaks the Environmental Protection and Management Law of Liberia, which requires the EPA to publish the spillage in a newspaper and broadcast it on a radio station

- The DayLight has frowned on the other news outlets from publishing a press release from the EPA on the publication-concealment issue without contacting The DayLight or adding its side of the story provided in a well-circulated email

MONROVIA – The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) lied when it suggested The DayLight failed to contact the agency for a story on chemicals that spilled from a Bea Mountain Mining Corporation plant into a river in Grand Cape Mount County in February this year.

Over a week ago, The DayLight reported that the EPA had concealed the report on the findings of the spillage. The report found that the waste plant at the New Liberty Goldmine leaked cyanide and copper sulphate into the Marvoe Creek and further into water sources in Jikondo in the Gola Konneh District. The chemicals, used to mine gold, are dangerous to people’s health and can lead to death. The spillage is the second in the last two years and the fifth in the last decade.

After the report, the EPA issued a press release, calling The DayLight story as a “diabolical lie.” It suggested that The DayLight did not check the site or contact its communication team before publishing its story.

“The Agency encourages media houses and individuals seeking information on the workings of the EPA to check its website and or contact its media and corporate communications office for information about the agency,” The EPA said in the release.

“The EPA is stunned that an online publication that [prides itself] as a credible outlet will depart from truth-telling as a core standard of journalism to telling lies to satisfy its funders’ criteria,” it added.

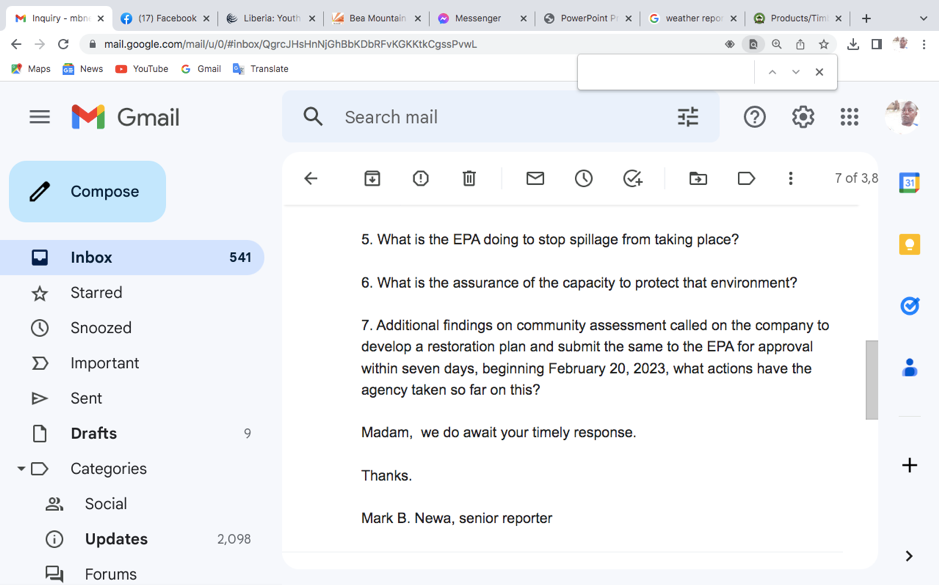

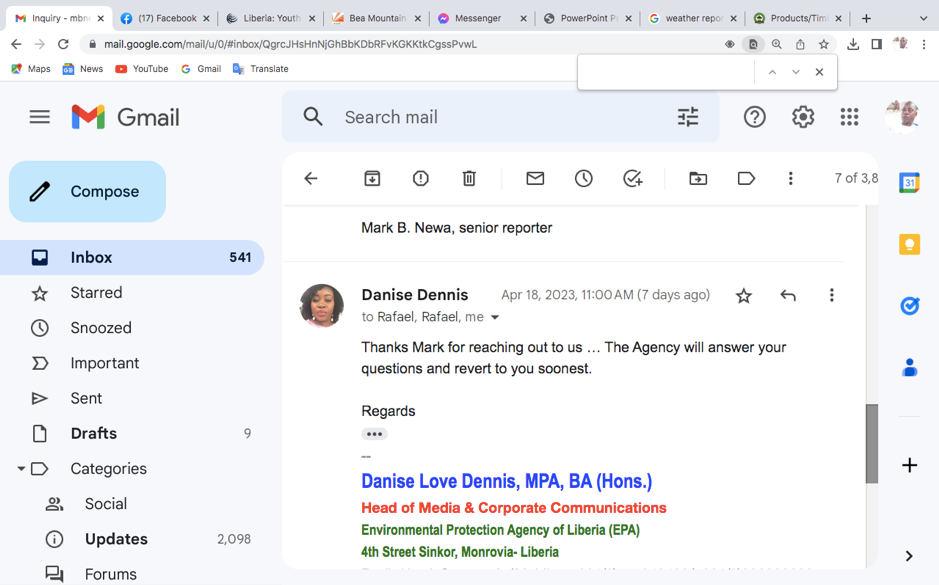

But the release contradicts the facts. The DayLight had contacted Danise Dennis-Dodoo, the head of EPA’s corporate communication office, four days before the story was published. In fact, one of seven questions Mark B. Newa, the reporter who did the story had raised, concerning the publication of the report. “The agency will answer your questions and revert to your soonest,” Dennis-Dodoo said in a reply to the email at the time. Those answers have yet to come more than two weeks after this reporter’s email.

The DayLight has expressed concern over EPA’s failure to acknowledge the environmental newspaper contacted the agency. “The fact that the press release here does not mention that is defamation in itself,” said Director/Managing Editor James Harding Giahyue.

Report Concealed

The date EPA published the February 19, 2023 report—and other documents on the website—is not reflected. However, The DayLight analysis of the document shows it was published on April 5, 2023. That was more than a month after the pollution.

Following last year’s spillage, the EPA issued three different statements. One booked Bea Mountain for that spillage, one reaffirmed its findings, and another dramatically cleared the company of any wrongdoing. All those statements were posted on Facebook, a preferred medium of communication for Liberians at home and abroad.

Unlike last year, the EPA made no public statement on the current spillage, which apparently indicates the agency tried to keep the spillage out of the public glare. The pollution was grave and residents of affected towns and villages had been prevented from drinking from creeks in the area for at least 45 days, according to the report. It was unclear whether they are allowed to use the waterfronts now.

The EPA probably violated the law by not widely circulating the report on the current spillage. The law says the EPA may choose to publish and broadcast the spillage—pollution control, inspection and investigation, to name some—in at least a newspaper and on a radio station. The environmental law mandates the EPA to “ensure maximum participation by the Liberian people in the management and decision-making processes of the environment and natural resources.” It guarantees “environmental information and promotes disclosure for the ultimate benefit of the environment.”

But apart from that, the technical language in the report does not make it ideal for public consumption. That seemingly explains why there has been a public discourse on the spillage more than two months on.

Amid all of this, there is no public record that the EPA fined Bea Mountain for the spills this or last year. Public access to information is a right under the Environmental Protection and Management Law, while public participation is one of its guiding principles. The law also ascribes to the global “polluter pays” principle.

The report said Bea Mountain did not implement some of the recommendations from last year’s spillage but did not specify. It had called on the EPA to punish the company for violating the law and the terms of its waste permit. Bea Mountain has not commented on the spillage.

One-sided Reports

News outlets, including The News, that lifted EPA’s press release against The DayLight’s initial article failed to include the environmental paper’s side of the story. Giahyue had replied to the EPA email when it issued the press release that Tuesday. The email thread copied a horde of journalists and media institutions, including The News.

“Individuals and institutions accused in any story or a press release deserve a right of reply,” Giahyue said. “Publishing the EPA’s press release without trying to get our side is an affront to journalism.”

[CORRECTION: This version of the story corrects the previous to add the spill of 2018, making it five spills in the last decade]

Funding for this story was provided by the Green Livelihood Alliance (GLA 2.0) through the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI). The DayLight maintained complete editorial independence over the story’s content.