Top: A truck offloads Askon Liberian General Trading Inc.’s planks on Gompa Wood Field in Ganta on November 11, 2022. The DayLight/Gabriel M. Dixon

By Mark B. Newa

- Askon Liberia General Trading Inc., a Turkish-owned forestry company, runs at least one illegal logging operation between Ganta and Sanniquellie in Nimba County. It smuggles timber out of Liberia in containers, making use of online business platforms and social media

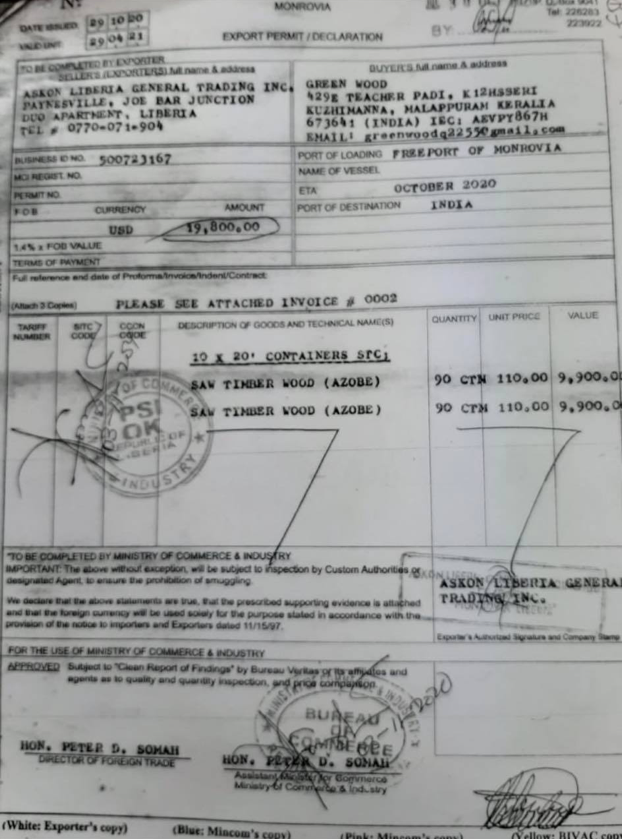

- Assistant Minister for Trade Peter Somah aided the company in smuggling expensive wood to India that cost over US$19,000, according to an illegal export permit The DayLight obtained. The money did not go into the Liberian government coffers, according to official records

- Askon also trades planks on the local market in Ganta, a business meant solely for Liberians

- Local Authorities shut down Askon’s operation in November 2022 over community benefits

- The rangers of the Forestry Development Authority not far from Askon’s worksite claimed they were not aware of its operations

ZULUYEE, Nimba – Last November, local authorities ordered a Turkish company to halt its logging operations in a forest between Ganta and Sanniquellie.

The Office of the Superintendent in Sanniquellie said Askon Liberia General Trading Incorporated did not have a logging contract and did not pay benefits to communities adjacent to the Garr-Mongbain Community Forest. Askon had come to Zuluyee in 2020, harvesting valuable redwood. The decision of county authorities followed some two years of residents’ anger over the company’s operations and suspicion it was illegally harvesting.

“The company did not come to us here,” said Faliku Kromah, a liaison and political affairs officer in the Superintendent’s office. “They passed the other way and went to do their thing in the forest.”

The local authorities were right. Askon does not have a legitimate contract to log in Liberia. It runs an illegal logging cabal that involves four Turkish nationals and several Liberians, including an official of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. That is according to Askon’s legal documents, official tax payment records, an illegal export permit and pictures from social media.

In addition to breaking forestry laws and regulations, Askon violated immigration and labor statutes, depriving Liberia of much-needed revenue, the tax records show.

‘See you soon… Turkey’

Askon began with a series of visits by a Liberian named Sylvester Suah to Turkey between November 2015 and December 2016, based on Suah’s Facebook page. Suah, a native of Nimba, held several meetings with his hosts and returned to Liberia. “See you soon, Istanbul, Turkey. Monrovia Liberia here we come…,” a December 1, 2015 post reads. “This is our own way of saying goodbye to each other my friend and business partner.”

By November 2017, Askon was established. It is owned by three Turks of the same family—Hasan Uzan (80 percent), Yeter Uzan (10 percent), and Faith Uzan (five percent)— according to the company’s article of incorporation. The remaining five percent of its shares are outstanding. The document was amended on September 14, 2020, but has not been enrolled at the Liberian Business Registry, a breach of the Business Association Act.

In a WhatsApp message to The DayLight late last year, Suah appeared to justify Askon’s illegal dealings. “I brought those people to Liberia for us to do bigger business but our country people in authority have their own way of delaying people’s progress,” Suah said while in Ghana to get a visa for another visit to Turkey. “That’s [why] you see it is starting that local way… to see how we will be treated before we can… expand.”

Askon’s operations in Nimba go back to 2019 when it signed an agreement with the Gba Community Forest in the Sanniquellie area. Askon agreed to pay US$35 per cubic meter of the logs it harvested on a 45-acre plot of land in that area, according to the agreement. It was unclear what happened thereafter, as there are no official records of it, except for a USAID report.

Today, Askon operates in Zuluyee, in the Yarpea and Garr-Mongbain forest region between Ganta and Sanniquellie. At its campsite, our reporter saw chainsaws, mobile sawmills, a 30-horsepower diesel tractor, several trucks and a bulldozer. Its workforce is between 10 and 50 workers, according to Lesprom, a Russia-based wood-trading platform on which the company trades. The region and the rest of Nimba account for 315,000 hectares of tree cover loss between 2001 and 2021. Only Bong County lost more (363,000 hectares), according to Global Forest Watch, which monitors forests across the world.

“The company is using a mobile saw that clears a large portion of bush and trees in seconds,” one chainsaw operator said, asking not to be named.

“The company is cutting trees all over here. All the trees will soon finish from here,” a community leader added under the same condition.

Five other people buttressed the operator and community leader. Photographs our reporter took show planks and thick, sawn timbers, commonly called “Kpokolo” at Askon’s campsite. Also called block wood, the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) recently banned kpokolo, as it became synonymous with illegal exports.

Pictures Hasan Uzan posted to his WhatsApp profile suggest kpokolo activities. One picture showcases squared timbers made from expensive wood stacked in containers and on wooden platforms. Another picture shows men uploading timber into a container truck. And one shows a variety of tree species with different colors. The profile reads: “Tropical timber center Askon sawmill, Monrovia, Liberia.”

Askon has exported different species of processed timber that are shipped to Asia and Europe, according to Global Wood Trade Network, a leading marketplace for timber and wood products. Askon’s LinkedIn account also identifies it as an export and import company, and it trades on other online marketplaces.

Illegal Permit

A permit The DayLight obtained shows Askon exported two 20-foot containers of ekki wood in October 2020 at US$9,900 each. Ekki wood or Azobe is a durable redwood used in shipbuilding and outdoor construction. It sold for US$293 a cubic meter on the international market that year, according to the International Timber Trade Organization. Askon sold the consignment to Green Wood, a firm in India, according to the document. Efforts to get comments from the company were unsuccessful.

There are other legality woes. Hasan Uzan is a resident of the Police Academy in Paynesville, according to Askon’s legal documents. However, Askon’s tax payment records show that he and Umit Gungor, a fellow Turkish national, have never obtained a resident or work permit. (Gungor came to Liberia on January 25, last year) That is a violation of the Aliens and Nationality Law and the Decent Work Act. Work and resident permits are prerequisites to conducting commercial logging in Liberia.

Assistant Minister for Trade at the Ministry of Commerce Peter Somah, signed the illegal document. Somah awarded the permit outside of Liberia’s timber-tracking system called LiberTrace. National Forestry Reform Law and Regulation on the Establishment of a Chain of Custody System bars trading timber outside LiberTrace. A pillar of Liberia’s forestry reform, the system tracks timbers from their sources to their final destinations, verifying legal requirements. It is a foothold of the country’s international timber trade, following decades of civil wars and mismanagement.

“No person shall import, transport, process, or export unless the timber is accurately enrolled in the chain of custody,” the law provides.

“Holders of forest resource licenses comply with all legal requirements facilitating the accurate assessment and remittance of forest charges and keeping illegal logs of the domestic and illegal markets,” according to the regulation.

Furthermore, the US$19,800 Askon paid for the two containers did not go to the Liberia Revenue Authority (LRA) as required by law, according to Askon’s tax payment record.

The Somah-issued Askon permit is unlawful, as it lacks features legal permits contain. It has no tracking barcodes and is not signed by the FDA’s legality verification department (LVD) and SGS, a Swiss firm that created the system. And it is not rubberstamped by the Managing Director of the FDA Mike Doryen.

In an interview with The DayLight, Somah sidestepped questions about the illegality of the permit, providing a lecture on trade instead. Then he displayed a file of papers he said were permits he had approved. Similarly, efforts to have him address a set of emailed follow-up questions four months later proved unsuccessful.

Illicit activities have rocked the forestry sector in the last three years or so. A recent Associated Press investigation found that Liberian officials appeared to collude with illegal loggers to export timber. Citing diplomatic documents, the report said Liberia may have a “parallel system” to the legal channel for timber exports. In January, a court indicted a former police chief, a customs officer, and three rangers over an illegal export deal. The policeman had been dismissed before the indictment.

FDA rangers—George Gaye, a ranger assigned at the Ganta checkpoint, and Bah Kromah assigned at the Guinea border—said they were not aware of Askon’s operations.

“The lack of mobility is hindering my operation as I am not able to patrol or visit nearby forest communities,” Bah Kromah told The DayLight in September last year. However, Askon’s operation site is just a 15-minute drive from Ganta and is an open secret in that region.

‘I need my money’

The villagers, too, said they were initially not aware of Askon’s harvesting their trees. “When we heard about this, we quickly called them to bring their equipment back to town,” recalled James Tokpah, an elder in Garr-Mongbain.

Thereafter, the villagers demanded Askon sign an agreement with them, according to several townspeople The DayLight interviewed. In the end, the illegal loggers promised to pay the community US$1,500 for every 1,000 pieces of timber, which Askon did not pay. That sparked anger, leaving local authorities to shut down its operations late last year.

By November, Askon’s world was crumbling down. In addition to the villagers, it owed its workers and petroleum dealers, according to Hasan Uzan. One of the workers said, “I need my money to pay my school fees and rent.”

Suah declined to make further comments on the story, despite accepting an interview months earlier. He lunged into The DayLight for protecting the interest of the international community, and not companies. “When I am ready, I will write my own story,” he said at his home in Ganta.

Hasan Uzan, Askon’s majority shareholder, denied exporting timbers with the permit when The DayLight tracked him down in Zuluyee. He refused to make further comments, referring our reporter to Suah, who he claimed was Askon’s owner.

On November 11, last year, The DayLight witnessed a truck Askon owns or hired offload planks for sale on the Gompa Wood Field in Ganta. One of the dealers, who preferred anonymity, said that the company frequently sold planks there. That breaks the Chainsaw Milling Regulation, which prohibits foreign nationals from selling planks in Liberia.

[Gerald C. Koinyeneh contributed to this story.]

The story was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).

Facebook Comments