Top: Smoke billows from a sawmill operated by Krish Veneer Industries Incorporated in New Buchanan, Grand Bassa County. The DayLight/James Giahyue

By Emmanuel Sherman

- Residents in communities affected by Krish Veneer Industries’ sawmill in New Buchanan, Grand Bassa County, complain of daily noise and air pollution

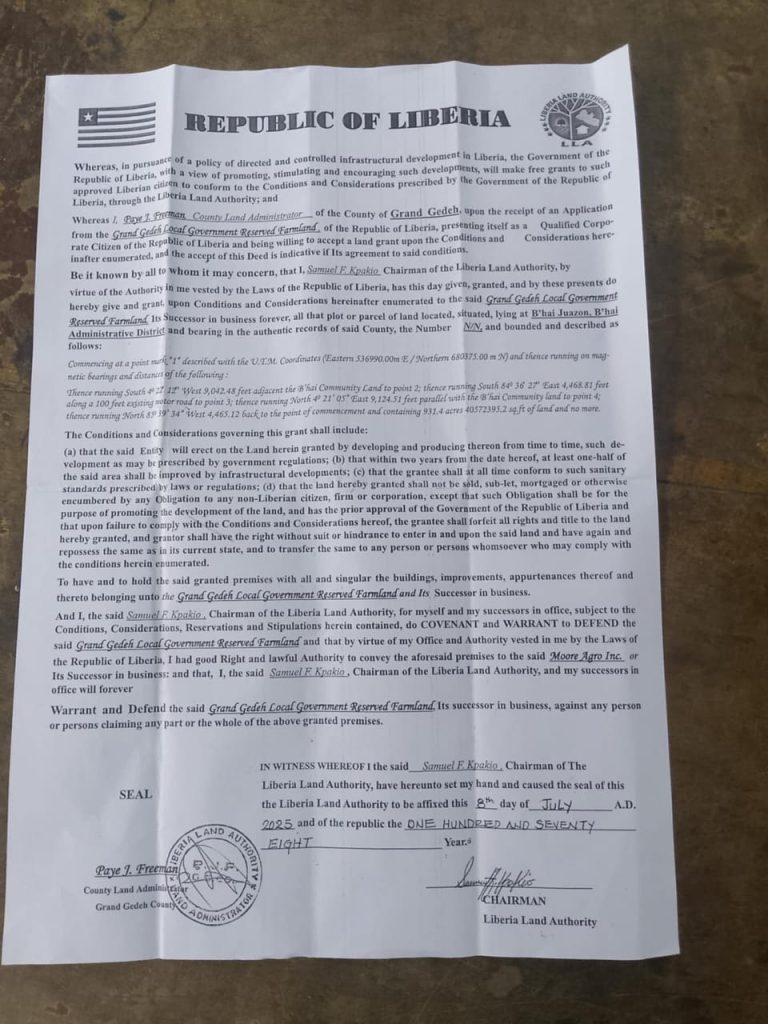

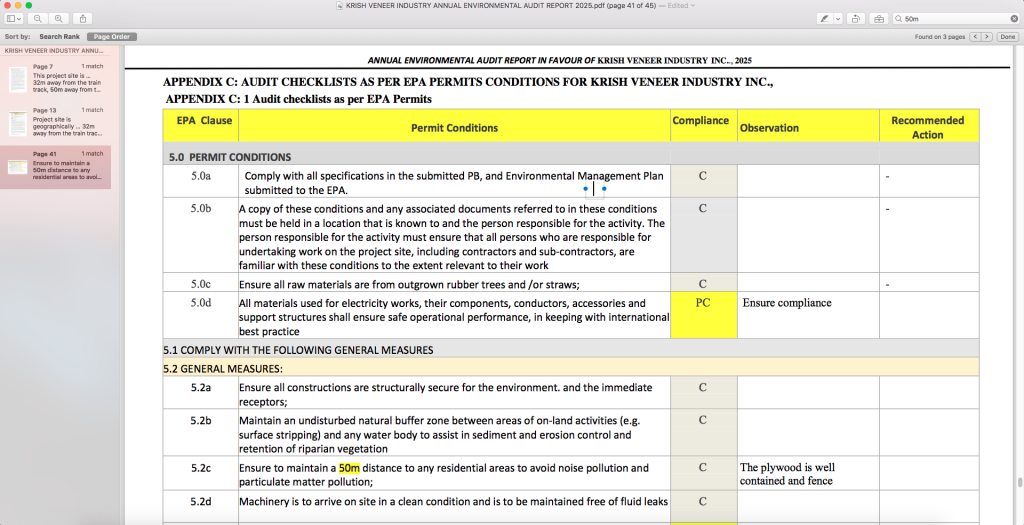

- Krish’s environmental permit requires a 50-meter distance from any residence. However, satellite imagery shows several homes much closer to the facility.

- An independent verifier finds Krish complies with its environmental permit, but inconsistencies undermine findings.

- The evidence establishes that the verifier doctored the report, covering up the sawmill’s pollution trail.

NEW BUCHANAN, Grand Bassa County – Seedaye Mingo, a grandmother in her 60s, sits and washes in front of her house, just a few yards from a large sawmill. For her, living near the sawmill, a fresh breeze has become a distant memory.

“The smoke can be black,” Mingo said. “It can smell.”

Mingo is one of several residents in five communities in New Buchanan, Lower Hardlandsville, who are impacted by the sawmill. Residents say they are experiencing some of these health issues. They complain of nonstop chainsaw buzzing and rattling from morning to evening, and smoke from the factory’s huge chimney clouds the entire area, covering everything. A video, shot by one resident, shows smoke billowing from the sawmill into the community.

Krish Veneer Industries, an Indian-owned company, runs the gigantic sawmill. Established in 2019, Krish produces and exports timbers, plywood, and veneer, a decorative wooden material. It has a workforce of 300 people and processes between 25,000 and 27,000 cubic meters of wood yearly. It was dedicated last May by Vice President Jeremiah Koung, which is likely the largest sawmill in the country.

Krish’s environmental permit requires the sawmill to be at least 50 meters away from any residence to prevent pollution. However, satellite imagery, analyzed by Nerisa Group of Companies, a DayLight affiliate, shows that several homes are just a few meters from the facility.

This indicates that residents such as Mingo are exposed to noise and invisible particles suspended in the air. Noise exposure, scientists warn, can cause high blood pressure, heart disease, sleep disturbances, and stress. Similarly, suspended particles can lead to heart and lung diseases in people, and impair visibility, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“The smoke is getting us blind and making our children sick,” says Junior Toe, a resident of Peace community, which hosts the sawmill.

“The pollution is a serious problem. The smoke affects not only adults but also children,” said Pastor Charles Gray of Success Community.

Daniel Larwubah, EPA Grand Bassa County Coordinator, said the agency needed to conduct a study to confirm the community’s concerns. He says he will inform the head office in Monrovia to send a team to the area.

The sawmill also poses a more direct threat to residents. Last year, ashes from the flames transferred to Pastor Gray’s makeshift house. Fortunately for him, neighbors ran to his rescue and cut off the fire.

On another occasion, flames from burning wood waste caught a resident’s clothes just outside the facility.

“I decided to take the clothes from the sun, but the flames from the fire in the fence had already burned the shirt,” says Beatrice Jacobs. Paul Harris, the chairman of Prosser, and other residents, corroborate Jacobs’ story.

After those incidents, the community wrote Krish in January last year, complaining about the danger the sawmill posed to the neighborhood, but got no reply. Harris says they also wrote to the Environmental Protection Agency of Liberia’s Buchanan office, but also got no reply.

So, in June that year, residents complained to the Office of the Superintendent of Grand Bassa County. Before her death, Superintendent Julia Bono held a conference between the community and Krish in June, a Ministry of Internal Affairs document shows.

In the meeting, the late Bono asked the company to find somewhere else to dispose of its waste, according to Harris. She died that November. However, Krish obeyed and stopped burning its wood wastes in the open. The DayLight observed that following several visits there, it remains the case.

A Krish contractor, who asked not to be named because he was unauthorized to speak, confirmed the change. “We use matches to light the fire and put big wood in the oven. The fire would burn throughout the day from 8 am to 8 pm,” he tells this reporter.

Larwubah admits to discussing with Harris about Krish. However, he denies receiving any communication, though the community mentioned that in their letter to the Office of the Superintendent.

Krish did not reply emailed questions on The DayLight’s findings and the residents’ allegations. The newspaper contacted a Krish executive, but he hung up the phone once this reporter introduced himself.

Inconsistencies

The EPA of Liberia certifies independent firms to conduct an environmental audit to find out whether the project complies with legal requirements. By law, the regulator fines a company that violates its permit provisions, based on the audit’s findings.

In Krish’s case, the Monrovia-based Environmental Consultancy Incorporated (ENCO) conducted the audit of the sawmill.

“Krish Veneer Industry is operating in a very effective and proficient manner in safeguarding the environment and its workforce…,” the audit report reads.

But residents dismiss those findings, saying they are unaware that ENCO conducted an environmental audit on the sawmill.

“Nothing of such,” says Joshua Howard, a spokesperson for the community. “They never came here in the community.”

ENCO determined Krish was “compliant” with the 50-meter provision. It established that the facility was a “well contained and [fenced].”

The satellite imagery, however, shows several homes just a few meters away from the sawmill’s fence, some 11, 12, 16 and 22 meters close to the facility. This evidence supports residents’ stories of flames from the company’s yard ending up on their premises next door.

Also, ENCO found that Krish did not employ an officer to handle community complaints in line with its environmental permit. Yet, ENCO marked Krish “compliant” in that area, an inconsistency.

The DayLight found other inconsistencies in the environmental audit report. ENCO reports that Krish respected cultural and historical sites, even though there are none in the community.

It found that Krish’s raw materials were from “outgrown rubber trees,” and that the community was forested. In reality, New Buchanan, where the sawmill sits, does not have a forest. Instead, it is one of the fastest-growing suburban communities with mushrooming homes and businesses on the Buchanan-River Cess highway.

ENCO misplaces its recommendations for finding in the “noise pollution” and “air quality control” portion of the report. It also mistakes findings for recommendations.

These inconsistencies, along with residents allegedly not partaking in the audit, prove that ENCO doctored the report, covering up Krish’s noncompliance.

The evidence indicates ENCO copied details from a 2024 report it had compiled for C&C Corporation (CCC) on the Mavasagueh Community Forest in Compound Two, about a 30-minute drive away. Interestingly, CCC supplies Krish with logs, and both companies have the same general manager, Clarence Massaquoi.

The CCC report was as problematic as the Krish audit report. While assessing potential impacts of CCC’s operations, it consulted only 24 of 39 affected communities.

Townspeople would protest their exclusion, leading to fresh elections that ultimately incorporated the 15 towns and villages left out.

ENCO did not reply to emailed questions, and when contacted, declined to speak to The DayLight.

“Go and ask the EPA,” said James B. Konowa, ENCO’s lead environmental auditor, who is a mining engineer. “We are accountable to them, not to you.”

Integrity Watch Liberia provided funding for this story. The DayLight maintained complete editorial independence over its content.