Top: Men work at a palm oil mill formerly owned by Equatorial Palm Oil (EPO) now run by Liberia Natural Produce Incorporated (LNPI) without the approval of the Liberian government or the consent of local people. The DayLight/James Harding Giahyue

By Varney Kamara

SHAMPAY CAMP – Liberia National Produce Incorporated (LNPI), an oil palm company that encroached on an abandoned palm plantation in Sanquin District, Sinoe County about a year ago, continues to run the facility despite not meeting legal requirements, including the consent of the local landowners.

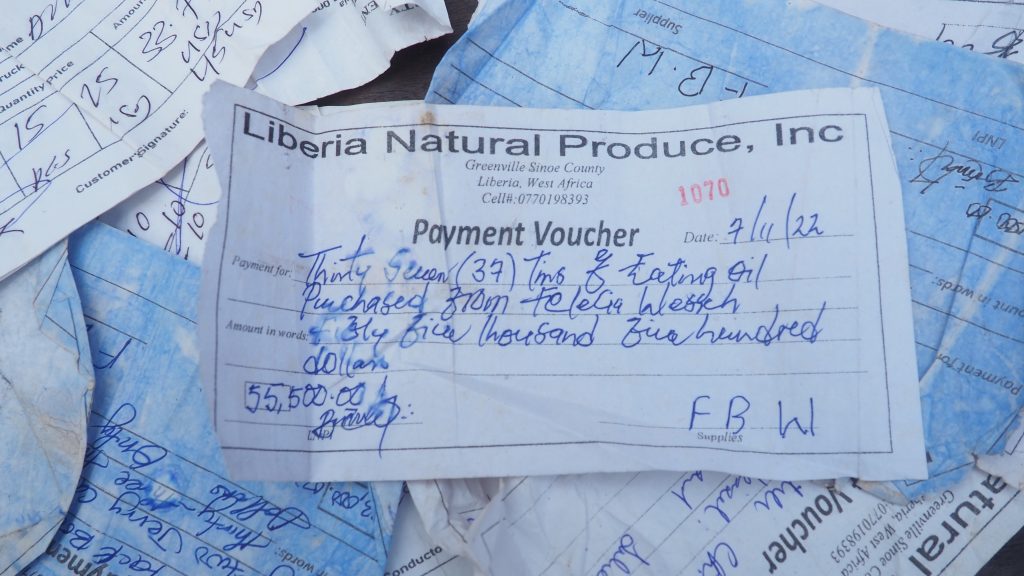

In 2022, LNPI purchased the 8,400-hectare palm plantation in the Sanquin District for about US$445,000 from Equatorial Palm Oil (EPO), which had abandoned the facility three years earlier. However, LNPI has not regularized the takeover to operate. A DayLight investigation in August found that the company forced residents out of the plantation with the aid of armed police officers.

Now two months after the investigation, LNPI continues to operate the facility. New evidence and interviews conducted by The DayLight show that LNPI is not compliant with several Liberian laws and international best practices.

This supports the Ministry of Agriculture’s claim that it was unaware of LNPI’s operations. Legally, the Inter-ministerial Concession Committee, including the Ministry of Agriculture, the Bureau of Concessions and the National Investment Commission (NIC), approves takeovers.

The DayLight has seen a copy of the LNPI draft concession agreement, without key signatures, including then-President George Weah and then-Minister of Finance Samuel Tweah’s.

In a September response to The DayLight’s queries, NIC appeared to corroborate the Ministry of Agriculture’s statement. “The Government of Liberia… provided consent to the transfer, contingent upon the new buyer’s commitment to resuscitate the plantation and ensure compliance with all applicable taxes and regulations under [the] Liberian law,” wrote the Executive Director of the NIC Melvin Sheriff.

Evidence of LNPI’s operations is aplenty. The DayLight witnessed workers active at a palm mill the company renovated, with smoke rising from the facility overhead. Fresh brushing spots along the main road to the Shampay Camp, where workers of the defunct Butaw Oil Palm Company lived. A giant-wheeled transporter plied the road.

Before announcing the takeover, LNPI secured an environmental permit from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) after conducting an environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) between February and May last year.

With the help of armed police, LNPI has forced camp dwellers out of the plantation and allegedly seized their personal belongings. Nestled between hills and forests, Shampay Camp once thrived and served as a palm oil hub. People in and out of the area exploit the plantation to produce palm oil.

“We are living in hell here. They always make us scared. They took my freedom mill machine and spoiled it. We have no space to breathe,” said Fatu Sheriff, an elderly woman.

“One man from the company came to my house. He told me that if I did not stop buying and selling oil on the camp, he would order the security to beat me and take me away from the camp by force,” Sheriff added.

“Then, I looked in his face and told him that if he wanted to, he should go ahead and kill me, but I was not taking one foot from my house to go anywhere.”

Sheriff’s comments and others The DayLight heard validate townspeople the newspaper interviewed in June this year. LNPI did not return emailed queries in response to issues in this story.

LNPI proposes that locals allow the company to operate. In the document, seen by The DayLight, LNPI proposes to pay benefits to the community, including a monthly payment of US$1,000 to the community development fund, rental fees, and engaging in community development. Once these conditions are satisfied, the agreement allows for the company to operate without “any disturbance or embarrassment.”

“This is manually agreed by the parties that the monthly payments are an advance on any community’s obligations the company needs to pay once the concession agreement has been approved by the Government of Liberia,” reads the proposed MoU.

The local community rejects the proposed MoU.

“The company is operating on our land without authorization,” said Ericson Pyne, a youth leader in Tarsue Chiefdom. “We have repeatedly asked them to show us the concession agreement, but they have refused.”

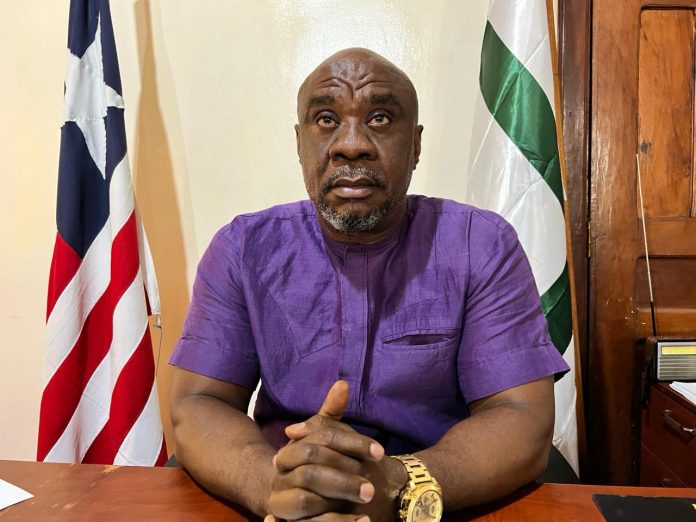

The Sinoe County’s Superintendent Peter Wleh Nyensuah sides with the LNPI despite its glaring illegitimacy. In a letter to the Tarsue Chiefdom last month, Nyensuah urged locals to let the company operate.

“The Taruse community having received benefits under the now expired MoU from LNPI, the community lacks the standing to question the legitimacy of LNPI. The community can renew or renegotiate another MoU through the Office of the Superintendent,” read Nyensuah’s letter. Locals had filed a complaint with the Superintendent’s Office, expressing dissatisfaction over the company’s failure to present its concession agreement.

Nyensuah’s comments are not based on facts. In the MoU he referenced, the Tarsue Chiefdom did not empower the company to run the plantation. Instead, it granted LNPI the sole right to purchase palm oil from locals.

‘Organic palm oil’

LNPI’s involvement with the plantation violates the Land Rights Act and the principles and criteria of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a watchdog writing rules for the global oil palm industry.

Both the law and the RSPO rules recognize ancestral land ownership and communities’ right to consent to projects intended for their lands. Liberia created the law in 2018 and adopted the RSPO rules three years later. This means they were not nonexistent when EPO took over the plantation from Liberia Forest Produce Incorporated in 2008.

James Otto, a lead campaigner at the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI), urges LNPI to inform the community of its intent to operate on their land and obtain a concession agreement.

“The company needs to have a well-designed concession negotiation through the FPIC process,” said Otto, whose NGO helped lodge the successful complaint against GVL in 2013 for communities. “The company needs to provide all the proper information to the community.

“There should be a formal lease agreement between the company and the landowners before the company starts operation,” added Otto.

LNPI is noncompliant with the Beneficial Ownership Regulation, which requires businesses in Liberia to declare their beneficial owners or the human beings who own them. This rule helps combat everything from money laundering to terrorist financing.

LNPI is a subsidiary of Konnex Investments Limited, with 51 percent of the company’s shares. The remaining 49 percent unsubscribed, according to LNPI’s articles of incorporation. However, the Liberia Business Registry said it did not have a list of the company’s owners, violating the regulation.

Also, there is no record of Konnex Investments Ltd. on the official public registry of all British firms. Konnex is not on OCCRP aleph, operated by the Organized Crimes and Corruption Reporting Project, one of the world’s largest public databases of companies.

In a LinkedIn post last year, Uday Pilani, LNPI’s chairman per its website, identified himself as the owner of Konnex Investments Ltd. Pilani claims that the company uplifts indigenous communities, is RSPO-complaint and produces organic palm oil.

But the claims are the exact opposite of the company’s activities.

LNPI deceived locals into signing an MoU likely to gain control of the plantation before informing them about its takeover. It even violated the terms of the deceptive deal by extending it by several months.

That conduct breaks the RSPO’s first rule that requires oil palm companies to operate ethically and transparently. Because of the breach of that rule, the RSPO ordered Golden Veroleum Liberia to renegotiate an MoU with Tarjuwon, Butaw, and other areas after it was found GVL guilty of disrespecting those communities’ right to consent.

Then Pilani’s organic palm claim is not consistent with the definition of the phrase. Organic palm oil production involves sustainable farming that is environmentally responsible, socially equitable, economically viable, and prevents deforestation while protecting workers’ rights and the welfare of local communities, according to the RSPO. In contrast, LNPI’s activities undermine the descriptions of organic palm oil.

The Ministry of Justice, which negotiates concessions agreements, said it was investigating LNPI’s operations.