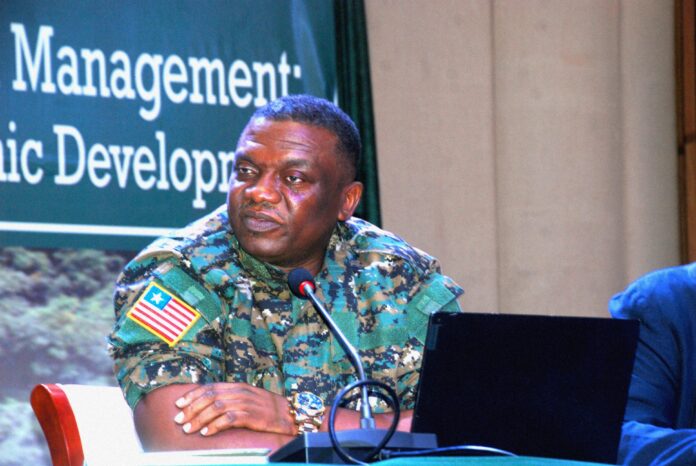

Top: The Managing Director of the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) Mike Doryen blamed villagers for illegal logging. However, Doryen awarded an unlawful permit, according to a document The DayLight has obtained. The DayLight/Mark B. Newa

By James Harding Giahyue

MONROVIA – commenting at an international forest and climate conference in January, the Managing Director of the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) Mike Doryen blamed loggers and villagers for certain illegal forestry activities.

“These communities are undermining our efforts to deal with violations,” Doryen told delegates at the event.

“People go in the communities and take money from other people to harvest and transport timber to town, harvesting double board-foot outside what is required by law. It is illegal logging,” Doryen added. He meant compact, squared woods, smuggled in containers, which has rocked the logging industry to its core. The industry calls it “kpokolo.”

Ironically, an export permit the FDA awarded to a company years back, obtained by The DayLight, suggests Doryen himself is an architect of the illegal trade.

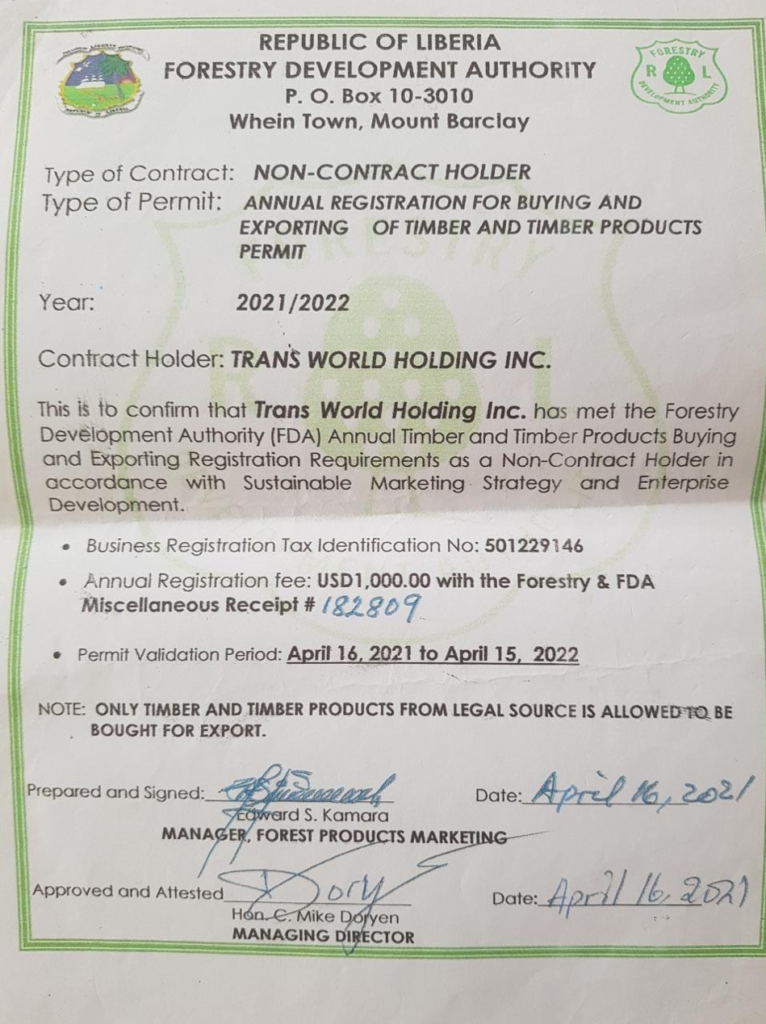

Doryen and Edward Kamara, the FDA’s manager for forest product marketing and revenue forecast, issued the permit to Trans World Holdings Inc. outside the legal channel to export timber.

“This is to confirm that Trans World Holding Inc. has met the Forestry Development Authority annual timber and timber products buying and exporting registration requirements as a non-contract holder in accordance with sustainable marketing strategy and the enterprise development,” read the document, signed only by the two men, in April 2021.

The permit shows a stark variance from the ones created by the FDA chain of custody system called LiberTrace. For instance, the document was valid for a year, unlike legal permits that are issued on a shipment-by-shipment basis. It contains at least one human error, something the legal permits are free of. It is the same as a permit Doryen awarded to an Ivorian-owned firm named Porgal, exposed in an investigation last year. The LiberTrace system is Liberia’s sole safeguard for the trading of legal timber on the international market.

The Trans World permit Doryen approved goes against the National Forestry Reform Law and Regulation on the Establishment of a Chain of Custody System. The law says, “No person shall import, transport, process, or export unless the timber is accurately enrolled in the chain of custody.” That ensures “Holders of forest resource licenses comply with all legal requirements facilitating the accurate assessment and remittance of forest charges and keeping illegal logs of the domestic and illegal markets,” according to the regulation.

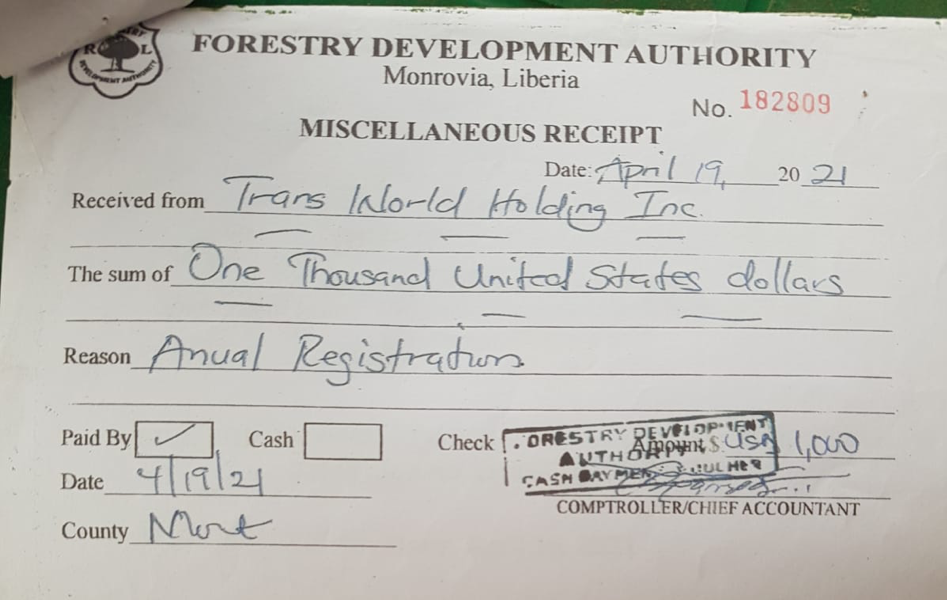

Trans World paid US$1,000 for the permit, based on the receipt of the payment, obtained by The DayLight. There was no record the company paid the fee to the Liberia Revenue Authority, the government’s agency that collects taxes. Also, the Liberia Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (LEITI) did not capture the payment as the law requires. Instead, it made the payment in an FDA account at the Liberia Bank for Development and Investment (LBDI), controlled by Doryen.

The permit authorized Trans World to purchase only legally sourced timbers. However, FDA checkpoints, under Doryen’s direct control have issued receipts for tolls businesses pay to transport kpokolo. There is no record rangers verified the sources of those woods before issuing receipts, Known as waybills in forestry.

Waybills

Ziama Kpoto, one of Trans World’s owners, claimed he received several waybills to transport wood from different parts of the country. Kpoto presented two waybills, including one from a kpokolo trader in Nimba. The other shows rangers received L$90,820 for 100 pieces of kpokolo of a first-class species called Iroko, and 130 planks. The kpokolo timbers measured six inches high, 10 inches wide and nine feet long. The transaction occurred on February 27, 2020, in Saclepea, Nimba County, according to that waybill. However, Kpoto did not show any waybills related to the permit he received from Doryen.

Like a dozen waybills The DayLight has obtained, the Saclepea document is unlawful. By the chain of custody regulation, companies make waybill payments within LiberTrace system, not by rangers. Legally, the FDA should issue them in books of ten waybills, with US$150 per book. They must have an identification number, show the route of the transport, and contain the final destination of the timbers. Also, they must have the total volume, not just the sum of individual timbers as it is with kpokolo waybills.

‘We’re not illegal loggers’

Kpokolo operations have rocked the forestry sector, especially in the last three years, with Nimba, Gbarpolu and Grand Cape Mount County hubs. Kpokolo operators The DayLight interviewed put their number between 60,000 and 80,000 countrywide, including everything from tree finders to transporters.

Kpoto was adamant kpokolo loggers operate outside of the law, saying their permits and waybills legitimize the trade. He claimed Doryen and Kamara misled them.

“[Kamara] is not telling us the right thing. We have [met him]… to tell us what to do,” Kpoto said in an interview with The DayLight. “You gave us a document. When we go to work and come you say the chain of custody. What should we do?

“Up to now, he has not given the idea. He only collects money from us. So, you can’t call us illegal loggers,” Kpoto added. His comments echoed ones he had made on posts on The DayLight’s Facebook. He presented some documents related to kpokolo productions in communities in Gbarpolu, one dating back to 2018. He said Trans World did not export any timber under the permit, a claim The DayLight could not independently verify.

Kamara dismissed Kpoto’s “misconceptions.”

“Mr. Kpoto was never registered and issued an annual permit/certificate to harvest logs or buy logs from chainsaw milling operations for export,” said Kamara, who announced a ban on kpokolo Wednesday, February 15.

Kamara claimed the FDA had issued “tens of these documents” to businesses across the country. He did not state how the FDA intended to prevent illegal timber trade having issued the permits outside of LiberTrace. And he also did not say why the FDA did not make payments for the permits and waybills to the LRA, or published them.

“We appreciate you all and we understand the anxiousness as [you] endeavor to satisfy [your] funding sources by running away with any story without understanding the rationale,” Kamara said, though he was responding to interview questions.

Doryen did not respond to a set of emailed questions. But the FDA has repeatedly accused The DayLight of “paid journalism deployed by our detractors to paint the FDA ugly in the eyes of the public.” On World Forest Day last week, Doryen accused partners of “double-standard games” for supporting “black hands” in the media.

This story was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).