Top: An elevated view of a 450-acre plot in the Gba Community Forest in Nimba County being cleared for a mine waste plant. The DayLight/Derick Snyder

By Esau J. Farr

- ArcelorMittal Liberia gave the Gba Community Forest US$150,000 to clear 450 acres for a waste plant, but locals misused the money

- Gba and Westwood Corporation signed an MoU to clear-cut the area anyway to make up for the stolen funds

- The deal includes an unspecified number of logs that a previous company had illegally harvested, costing the government revenue

- FDA authorized Westwood to skip harvesting requirements, including a mapping and GPS-recording of trees, undoing the immediate past administration’s legal order

- Westwood exported the timber to Italy, though the harvesting breaks Liberia’s timber trade agreement with the European Union

GBAPA, Nimba County – A cleared patch of the Gba Community Forest, a rocky conservation woodland, welcomes visitors to Sehyi Geh Town. Chainsaw-wielding loggers from a little-known company pile up logs in the clear-cut patch.

As it stands, Westwood Corporation has exported a combined 216 logs (921.124 cubic meters) from Gba, according to official records. The consignments were shipped in March to Sangiorgi Lugnami, a renowned Italian company. A third export of 142 logs has been requested for Bangladesh in the name of Leifwood APS of Denmark.

The exports, however, violate Liberia’s timber trade agreement with the European Union, known as the Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA). Under the 2011 agreement, only logs from legal sources, listed and verified, can be exported.

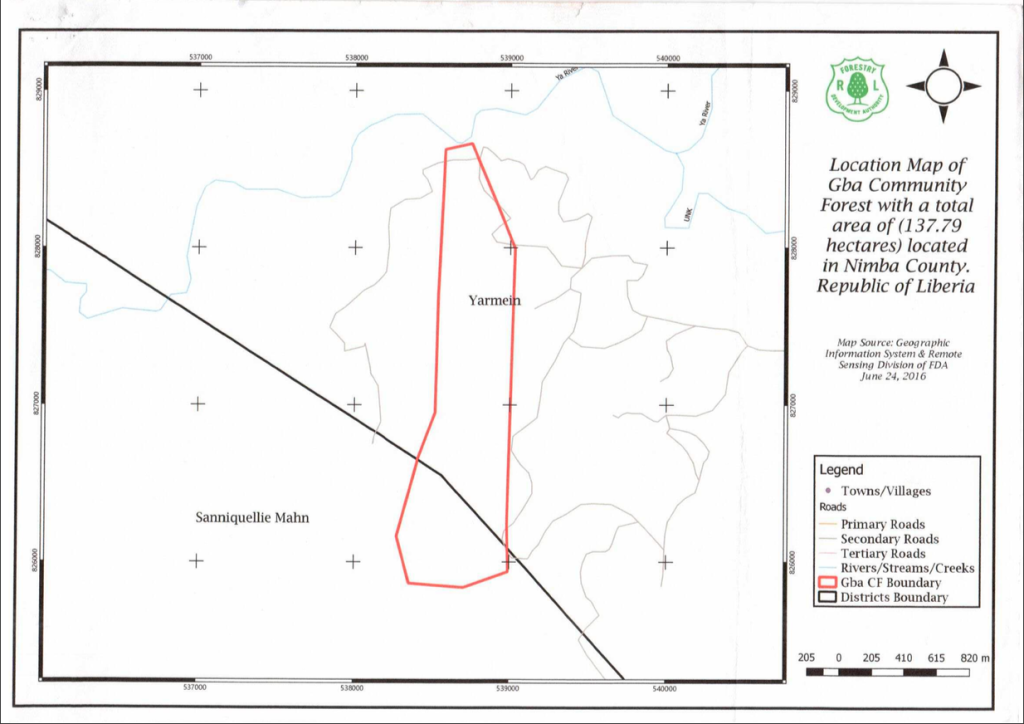

Westwood signed an MoU to clear-cut 450 acres (about 182 hectares) of forestland in the 10,939-hectare forest in Nimba County’s Yarmein District. Westwood agreed to pay Gba US$8 per cubic meter, with the agreement ending next month. A receipt, seen by The DayLight, shows that Westwood deposited US$3,570 into a Gba account last month.

“They have proven to us that they are capable of doing the job due to the machinery they have,” said Samuel Johnson, Gba’s leader, in March. Johnson died shortly after the interview.

But the Gba-Westwood MoU does not qualify the logs as legally sourced. There are five contracts or permits in forestry where legal timber comes from. They are: a forest management contract, a timber sale contract, a community forest management agreement, a private use permit, and a forest use permit.

The GBA-Westwood deal comes close to a forest use permit but differs from it remarkably. This permit is issued through a procurement procedure, for research, tourism, or local use, according to the National Forestry Reform Law and the Regulation on Tender, Award and Administration of Contracts and Permits. The VPA is based on Liberian legal instruments.

Two experts The DayLight interviewed, who preferred not to be named, said the Gba logs were only for domestic markets. They can be converted into planks, generate additional income for locals, and provide temporary employment opportunities for chainsaw millers.

The Nimba flycatcher

Initially, Westwood was not in the picture. ArcelorMittal Liberia had given Gba US$150,000 in 2014 to clear 450 acres for a mine waste plant. The money was also compensation for a 60-acre plot the company had earlier cleared.

Gba, however, misapplied the funds and failed to clear the area. Subsequently, Gba’s allegedly corrupt leadership was replaced in a scandal that rocked community forestry.

“[ArcelorMittal] paid US$150,000 to Gba to buy a machine or equipment to fell these trees or clear everything out of the site,” said Saye Thompson, the leader for the Blei Community Forest in the same region.

Nyan Flomo, who has taken up a leadership role in the wake of Johnson’s death, corroborated that account. ArcelorMittal did not respond to queries for comment up to press time.

The US$150,000 aside, the Westwood arrangement breaks Gba’s original MoU with ArcelorMittal. The document obligates the steel giant to identify trees and guide the clear-cutting process. It nullifies any other MoU associated with the harvesting, such as the one with Westwood.

Gba and ArcelorMittal are conservation partners. Gba is one of four communities adjacent to the East Nimba Nature Reserve (ENNR). Home to the endangered Nimba toad and Nimba flycatcher, the ENNR is part of the Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage site, running through Liberia, Ivory Coast and Guinea.

Gba co-manages the 13,500-hectare forestland alongside ArcelorMittal, FDA, Blei, Sehyi Ko-doo, and Zor. This collaboration helps protect plants and animals of that region, which, experts say, renders logging harmful to that ecosystem.

And the stakes are higher for Westwood, with Gba its first official operation. The company has experience in construction, having constructed a stretch of the Gbarnga-Lofa highway in 2014. Samuel Cooper, its CEO, declined to speak on the matter.

‘Inability to perform’

Permitting Westwood to export, the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) undid what its past administration had done to enforce the law. In a February letter, Managing Director Rudolph Merab excluded Westwood from cutting blocks—regulated forest portions where harvesting occurs. Merab, who did not return emailed questions, has spoken before about deregulation and a drive to increase timber exports.

“Following a desk review of your acquisition of the Gba Community Forest…, you are hereby approved to commence operations,” read the letter.

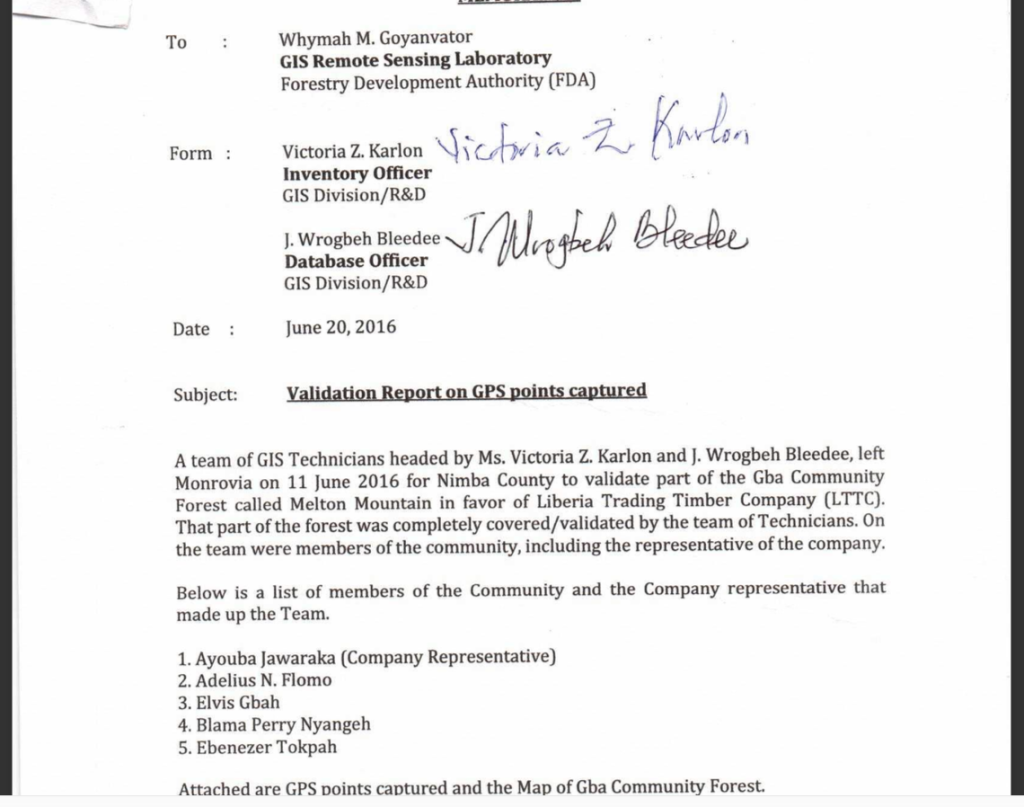

Merab’s action is the complete opposite of how the FDA handled the Gba case nearly 10 years ago. In 2016, Gba signed a similar MoU with the Liberia Tree Trading Company Thanry. However, the FDA administration then ensured that LTTC Thanry had an annual plan that contained blocks and a map to regulate the harvesting, at least consistent with the law.

Later, Gba terminated LTTC Thanry’s contract due to its “inability to perform,” bringing in Six S (6S) International Trading Limited.

Though Six S had the capacity, the FDA disapproved of the new company’s harvest because it deviated from the approved plan, several past and present FDA officials familiar with the matter said.

“I [confirm] that during my time at the [legality verification department], 6S did not receive any export permit in LiberTrace,” said Deputy FDA Managing Director Gertrude Nyaley. At the time, Mrs. Nyaley headed the department, which co-manages LiberTrace, the computer system that tracks Liberian timber. She said the company had a tax issue, but, like the anonymous sources, presented no evidence. Six S’s official number did not ring, and it did not answer emailed queries.

Whether unauthorized harvesting or taxes, the Gba-Westwood MoU included an unspecified number of the problematic logs that Six S cut. This violates the Regulation on Confiscated Logs, Timber and Timber Products.

Per the regulation, the FDA is required to investigate, seek a warrant to auction the logs, and fine Six S. Instead, Merab permitted Six S to sell the logs in question to Westwood for US$34 and US$55, losing that revenue.

‘Behind the Curtain’

Gba locals The DayLight interviewed said they were unaware of the Westwood agreement. They had only heard it through the sound of earthmovers and loggers in the forest.

“First, when they came, they just went into the forest and we said, ‘No, you don’t do things like that,’” recalled Aaron Lah, the town chief of Sehyi Geh Town. ‘“This is a town and people are here. Why did you people just come and not reach the townspeople before going into the forest?’”

The Social Entrepreneurs for Sustainable Development (SESDev), a Paynesville-based NGO training Gba’s leaders in forest governance since 2023, said it was not informed about the deal.

Thompson, the Community Forests Union’s head, said there were missteps.

“If you don’t share information on what you are doing, it becomes corruption,” said Thompson. “Everything is behind the curtain.”

Liberia Forest Media Watch provided funding for this story. The DayLight maintained editorial independence over the story’s content.