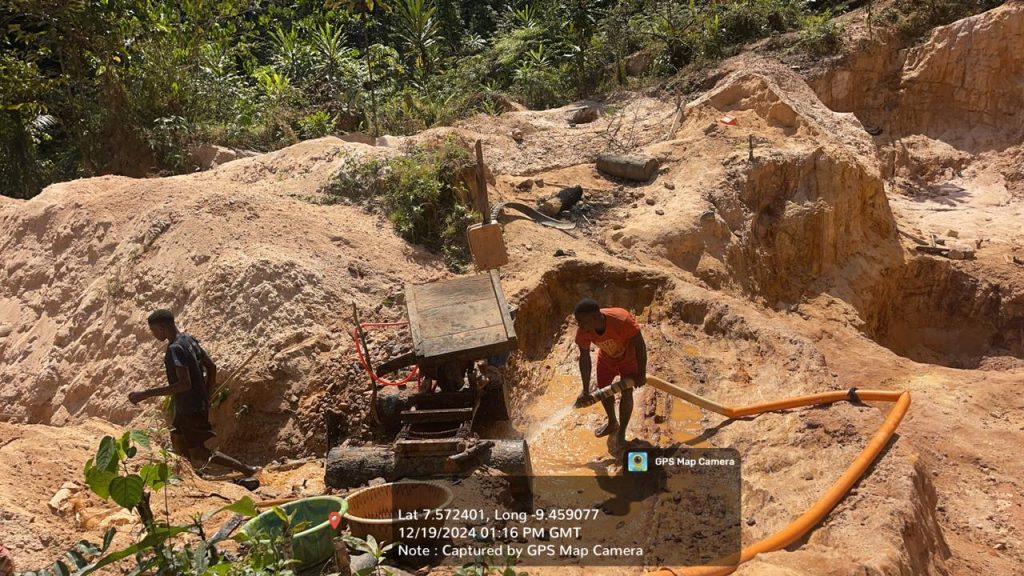

Top: Miners operate with an expired license in the Salayea Community Forest. The DayLight/Harry Browne

By Esau J. Farr

SALAYEA TOWN – In late May 2024, the Salayea Authorized Community Forest filed a lawsuit against a group of illegal miners for alleged unauthorized entry.

The Salayea Magisterial Court threw the case out, saying Ford Tabolo, the miners’ head, had a legal class ‘C’ or small-scale license. The court called on the Ministry of Mines and Energy, and the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) to resolve the matter.

But Tabolo’s miners continued to mine after the expiration of his license in August last year, according to the Ministry of Mines and Energy’s records. This means that Tabolo has illegally exploited the 8,270-hectare woodland for five months, nearly half of the lifespan of a small-scale mining license.

In a follow-up to previous investigations, reporters walked six hours to and from the community forest late last year and gathered evidence of Tabolo’s illicit mining activities.

“He (Ford Tabolo) is aware of our operation [mining activities] here and he is the one sponsoring us. If anybody has a problem with us, they will put it before our leader,” said Daddy Kanneh, the head of the mining camp.

The camp is first from Salayea Town towards Telemu deep into the forest at the foot of a red, muddy hill. Mine pits spread beneath a hill, with two tents made of palm thatches and tarpaulins. Five miners panned and sieved for gold with a water pump machine, which is prohibited for small-scale mining.

“If the forest people say we should stop mining, that one should be an agreement between them and our boss man,” added Kanneh.

The reporters walked another hour to Tabolo’s second goldmine. Perched on the banks of a stream, some 10 miners worked there—this time—with shovels, buckets, diggers and cutlasses.

Here, the miners built an inclined wooden stage with carpets. They poured muddy gravel on the carpeted stage, followed by water, which entrapped tiny gold nuggets.

Other mineworkers panned for the nuggets, while others dug gravels and transported them to the washing stage.

“Right now, we have around 30 persons here in the forest. The way we used to receive gold here, we are not receiving it like that. When we were using the machine, we were getting more gold but the forest guards came here and took it away,” said John Kollie, the camp’s manager. Kollie disclosed they got between a quarter and half of a gram of gold daily.

Reporters could not visit Tabolo’s third goldmine more than two hours walk away, as evening approached. It would have meant sleeping in the dark, humid forest, and compromising their safety. So, they collected testimonies from the miners who had worked there.

They spoke about how Salayea Community Forest guards seized their tools, including a machine, carpets and shovels.

The DayLight could not determine whether Tabolo had a license for all three goldmines, as he has three other expired licenses in Lofa.

Efforts to interview Tabolo did not materialize, as his phone was always off, and he did not reply to text messages. However, in a previous interview with The DayLight, the mine owner said he would upgrade his small-scale license to a semi-industrial scale license.

Mining with an expired license constitutes a violation, with up to a US$2,000 fine, a maximum 24-month imprisonment, or both for convicted offenders.

Conservation undermined

The community forest wants the miners out as the forest is under conservation. Salayea Community Forest is important for conservation due to its rich biodiversity, which has empowered local people.

The community forest runs alternative livelihood programs, including beekeeping, piggery, village saving loans, woodshops and cocoa plantations.

“We want the government to make sure to get the miners out of the forest because it is undermining our conservation efforts,” said Yassah Mulbah, the chief officer of the forest. “We will not rest as leaders of the forest until the right things are done.”

Last November, the current minister of Lands, Mines and Energy Minister, Wilmot Paye suggested that the mining law was superior to forestry laws and regulations. He made the statement in a WhatsApp chat with The DayLight.

“Your query should further focus on what the Minerals and Mining Law of 2000 says,” Paye texted and did not say anything thereafter.

Paye’s comments were incorrect. The mining law does not recognize community forestry—it is Liberia’s oldest extractive law. However, the Community Rights Law and the Land Rights Act of 2018 do. Both laws grant locals ownership of forestlands.

This story was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).

Facebook Comments