Top: Perhaps the most active forestry company in Liberia, Krish Veneer Industries exports round logs in addition to plywood and decorated wooden materials. The DayLight/Emmanuel Sherman

By Emmanuel Sherman

BUCHANAN, Grand Bassa – Over the weekend, Vice President Jeremiah Koung dedicated Krish Veneer Industries, perhaps the largest sawmill in Liberia.

Established in 2019, the Indian-owned Krish produces and exports timber, plywood and veneer, a decorated wooden material. It processes between 25,000 and 27,000 cubic meters of wood per year, according to an official environmental audit.

“This is a clear demonstration that India is not only a friend of Liberia in words but in deeds,” Koung told the dedication in Buchanan, Grand Bassa County. He toured the facility before breaking ground. A crowd of officials, chiefs and elders celebrated the event with workers dressed in protective gear.

“We are happy because these kinds of investments employ our people. If most of the logs can be put into cubes, planks and other things before getting them out of here, there will be job creation,” added Koung.

It might have been Krish’s dedication; however, the company has been in the news several times over noncompliance with the law. The DayLight has compiled these well-documented facts about Krish with supporting evidence:

Ghost of ‘Blood Timber’

The location Krish occupies is a symbol of sub-regional wartime atrocities. Between 1991 and 1997, Guus Kouwenhoven, a Dutch gunrunner and eventual war criminal, operated the Timber Management Corporation from there.

Koung referenced the facility in his speech. “I know the TIMCO yard used to be around here where we used to burn coal,” he recalled. “We were those children around here doing the wheelbarrow from here to town to carry the coals.”

TIMCO’s logs helped fuel the First Liberian Civil War (1989 – 1997). The Truth and Reconciliation Commission found that it and other companies illegally traded arms to Liberian militias and the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) of Sierra Leone, leading to mass killings of civilians.

This became known as “blood timber,” “conflict timber,” and “logs of war.” Former President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf mentioned it in a recent opinion.

Both Kouwenhoven and his business partner, ex-President Charles Taylor, were convicted of war crimes for their role in the murderous trade. Taylor is serving a 50-year sentence in a British prison. Kouwenhoven, meanwhile, was sentenced to 19 years in absentia by a Dutch court while he lives in South Africa.

Krish Illegally Operates

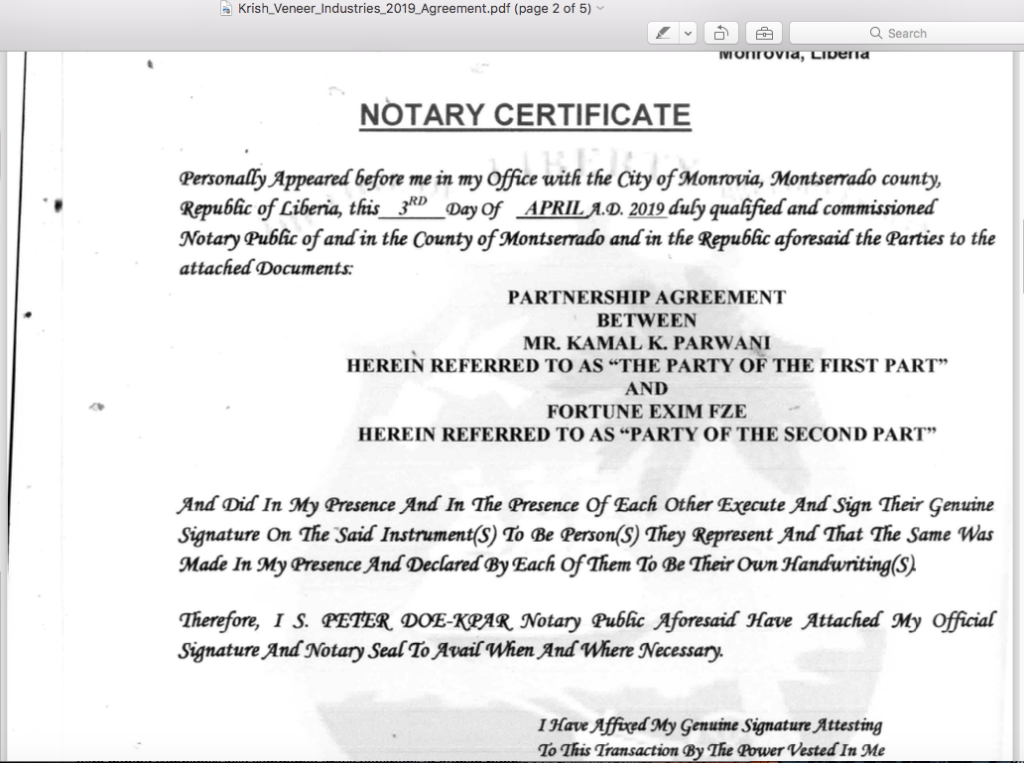

Krish is a partnership, not a corporation, as required by the Regulation on Bidder Qualifications and the Public Procurement Concession Act. According to its partnership agreement as of March this year, Antique Ahmed and Kamal Parwini are Indian nationals with 57 percent and 43 percent shares, respectively.

The legal instruments restrict forestry companies to corporations, not partnerships. They are a safeguard against the limited liabilities and lifespans of partnerships, as opposed to corporations.

The Public Procurement and Concession Commission has asked the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) to investigate Krish’s business status, according to a letter, seen by The DayLight.

Furthermore, Krish’s head office is in Buchanan, per its legal documents. That violates the National Forestry Reform Law, which calls for all sawmills to have their main offices in Monrovia. This rule is consistent with a provision of a repealed law that was used to hold TIMCO accountable in 2005.

Krish Rents from the FDA Boss’ Family

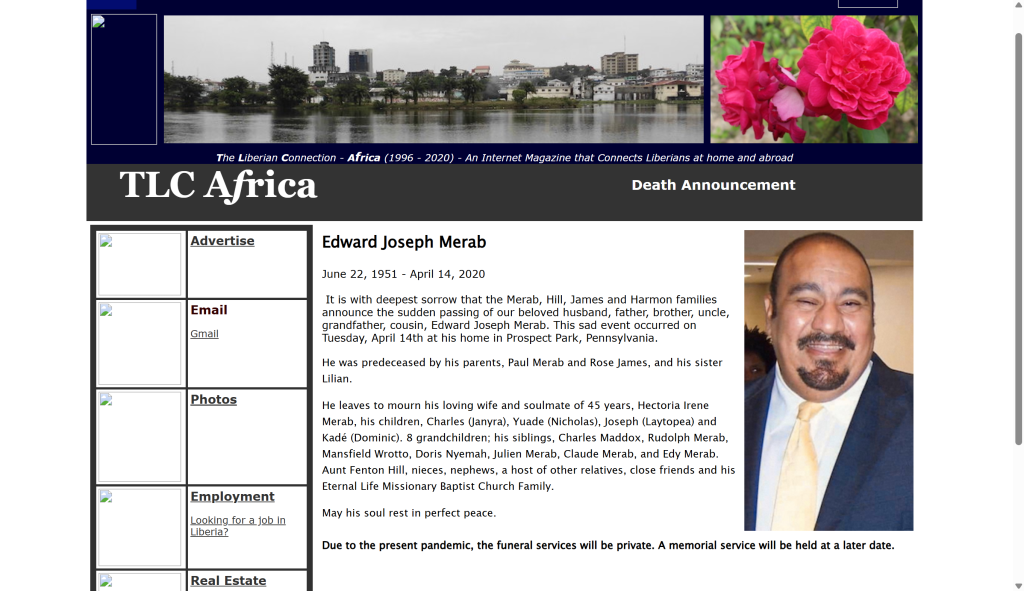

The land where Krish operates belongs to the family of the FDA Managing Director, Rudolph Merab. Merab inherited the plot from Rose Hill James, his late mother, who inherited it from Merab’s grandfather.

“Merab is from Bassa, and the property is owned by his grandfather,” said Clarence Massaquoi, Merab’s cousin. “Stephen Hill is managing the property; he is a cousin of Merab’s.

Khalil Haider, another of Merab’s cousins, corroborated that information. “That place is for Merab’s mother and her family,” Haider said.

The two men’s comments are confirmed by an obituary of Edward, Merab’s elder brother, which shows that the FDA’s boss is a member of the Hill family, the property’s original owners.

This establishes that Merab is caught between two interests involving Krish: a landlord and a forestry regulator. Such a clash breaks the Code of Conduct for Public Officials, which prohibits Merab from “situations of conflict that impair, or are likely to impair, the performance of their official duties.”

Krish’s Manager is Merab’s Cousin

Turns out, Clarence Massaquoi is not only Merab’s cousin but also Krish’s manager, according to FDA records.

Massaquoi is also an ex-employee of Liberia Wood Management Corporation, Merab’s wartime company. “I worked with Merab from 1999 to 2007 in a managerial role,” he told The DayLight in January.

Noteworthy, Massaquoi is ineligible to conduct logging activities in Liberia due to his wartime role. The Regulation on Bidder Qualifications states that wartime loggers must confess their crimes and restitute unpaid or stolen funds, something Massaquoi did not do.

Krish Benefits from an Unlawful Contract

Krish’s illegal logging love story with Merab and Massaquoi does not end with the pair’s family and work relationships.

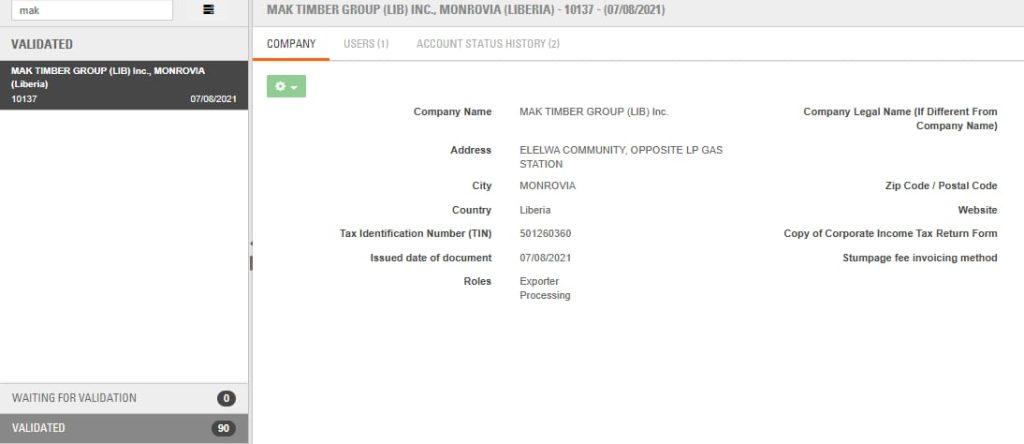

Krish does business with C&C Corporation, Massaquoi’s own company. Now C&C has a contract with the Mavasagueh Community Forest, a few miles away from Krish. “I can sell to my plywood factory. My buyers are in Buchanan,” Massaquoi said.

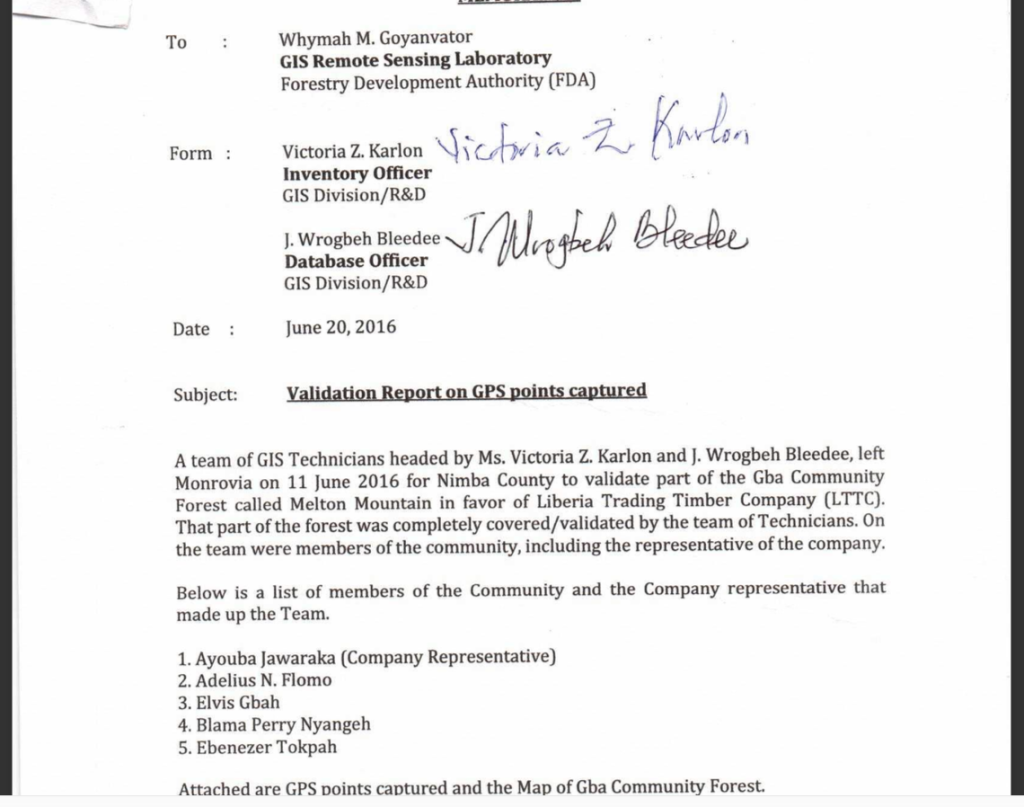

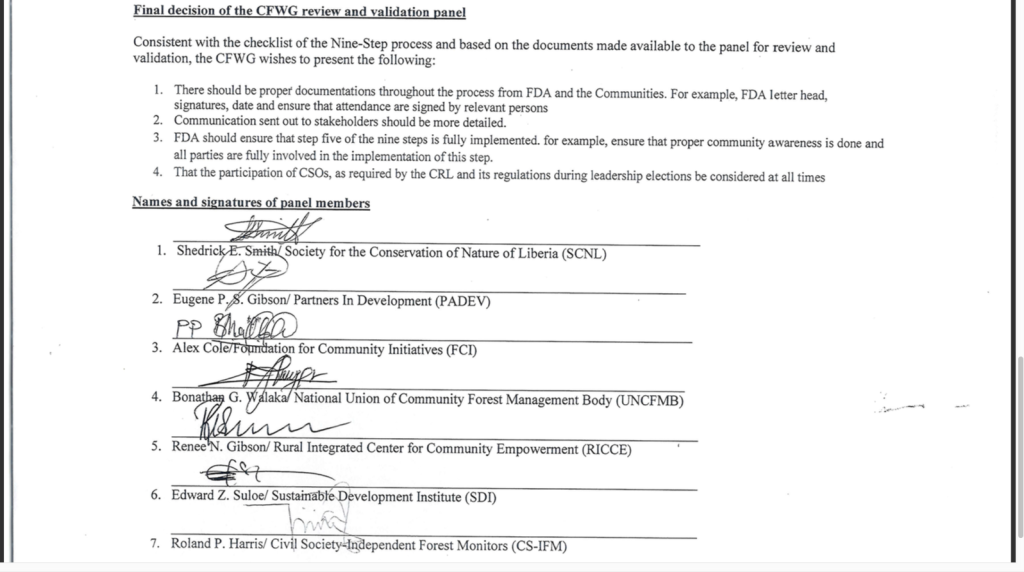

However, C&C’s contract did not follow the law, as the FDA had bypassed legal steps in Mavasagueh’s formation. There are nine steps in the formation of a community forest, characterized by locals’ participation and consent.

In Mavasagueh’s case, some communities adjacent to the forest were left out, there was inadequate awareness, and even people in the communities that the FDA recognized did not participate in the 26,003-hectare forest’s mapping exercise.

The FDA ignored the issues that actors raised, including the absence of civil society organizations during Mavasagueh’s election, which is a requirement.

Matters worsened when Merab allowed Mavasagueh to overlap private land, violating the Community Rights Regulation. Khalil Haider, Merab’s cousin and Paynesville resident, claims 3,200 acres in Mavasagueh.

Haider, who said he was Massaquoi’s step-brother, revealed Merab encouraged him to drop his claim for the contract to continue. Though Merab ignored The DayLight’s queries for his side of the story, Massaquoi corroborated the claim. “Haider and I settled… so the FDA should let the document be processed,” Massaquoi said.

Krish Exports Illegal Timber

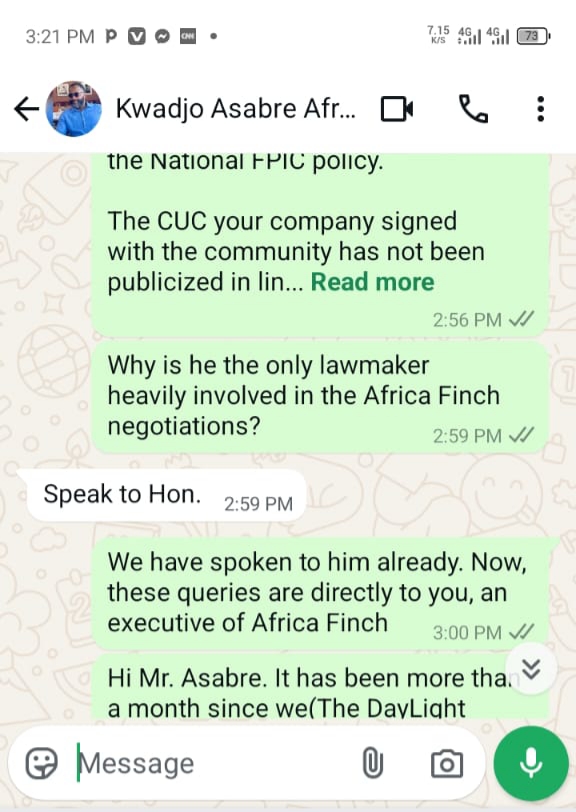

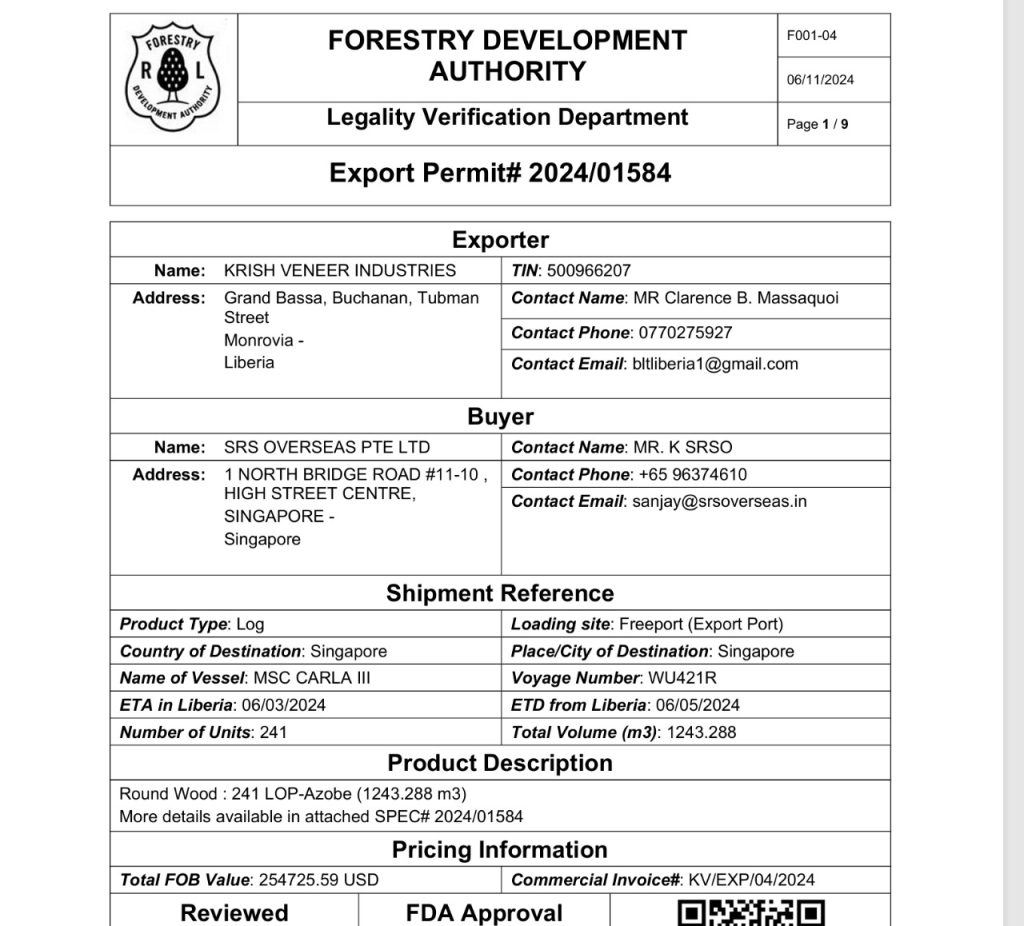

April last year, Krish exported 210 logs (1,243 cubic meters), illegally harvested, to Singapore. LiberTrace, the FDA’s computerized system that tracks timber, had red-flagged the logs, but Merab still approved their shipment.

Out of the 210 logs, 66 had minor issues, including differences between their species, sizes and lengths in the system, and the ones exported. A whopping 144, or nearly 70 percent of the consignment, had major errors. There were 66 of these logs whose harvest had not been approved by the FDA.

Krish exported at least three other times to Singapore and the UAE, with some 20 to 30 percent of the logs illegal.

This story was a Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ) production.