Top: Trucks transporting logs are stuck on a road in Vambo Township, Grand Bassa County, after community protesters set up roadblocks, demanding benefits. The DayLight/Ojuku Kangar

By Emmanuel Sherman

VAMBO, Grand Bassa – People claiming landowners of a community forest have protested against a company for allegedly sidelining them in a logging contract.

The aggrieved citizens of Vambo Township set roadblocks to prevent C&C Corporation (CCC) from transporting logs to Buchanan. Over 10 towns and villages, including Gblorso, Vahzohn, Baryogar, Boe, and Cee, participated in the protest.

“We have decided to set roadblocks because of the mismanagement of our resources without understanding,” said Abel Payway, youth chair.

“We did not sign the agreement with them, only a few groups of people. They formed a clique and did what they could without consultation with the citizens,” added Payway.

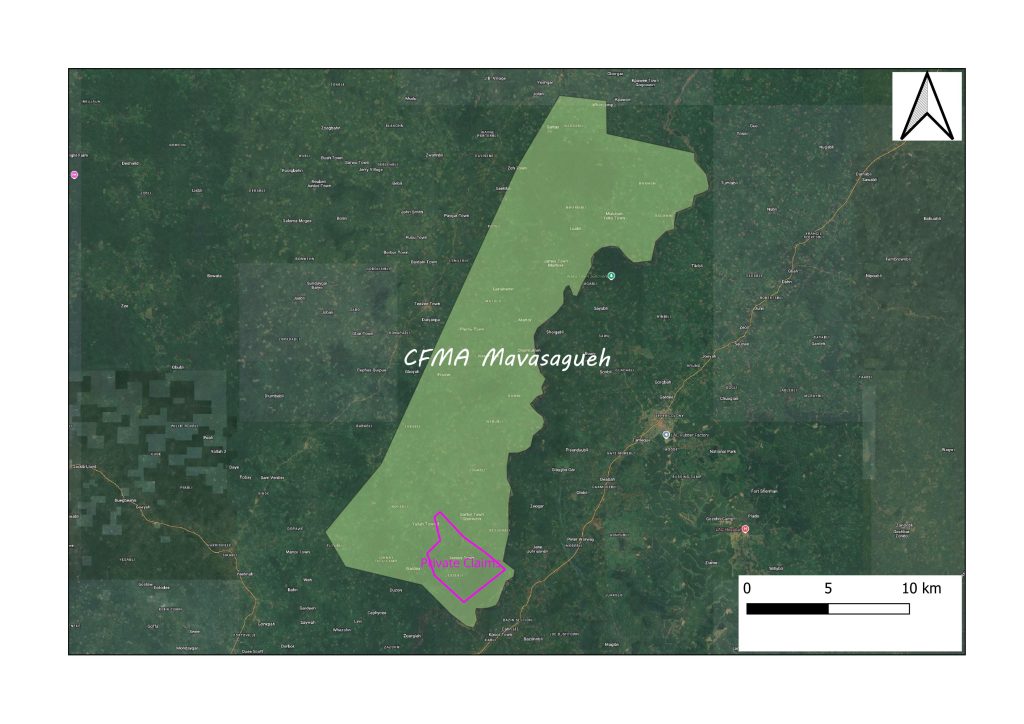

Last year, CCC signed a logging contract with 39 towns and villages adjacent to the Mavasagueh Community Forest, a 26,003-hectare woodland, in exchange for development.

But everything about the deal was illegal. An environmental assessment of the impacts of the CCC’s operation left out 15 towns and villages. Mavasagueh had been illegally established, and the company is ineligible for logging activities, a report review found, which a DayLight series corroborated. Some towns had criticized the Mavasagueh process for excluding them.

The protest followed months of failed negotiation. It echoes the illegalities of CCC’s operations and foreshadows likely future hostilities.

Rebecca Gblorso, a middle-aged protester, did not mince her words during a Daylight interview. “The company started extracting our logs without any benefit. They started hauling our logs last week Thursday. We feel bad and angry so we set the roadblock,” Gblorso said.

Jacob Cee, an elder in his late 80s was among the protesters.

“I am here to protect my township. I speak for all my elders, so when something is happening here and is not right I represent my community,” said Cee.

“The protest is a wake-up call for the company to meet our needs,” said Vambo’s Commissioner Nathaniel Clarke.

Daniel Dayougar, Vambo’s ex-commissioner and now CCC’s community liaison officer, refutes the protesters’ claim. “Togar Town is out,” said Dayougar, who is accused of handpicking the forest’s leaders.

Horace backs Dayougar. “Those towns that did the protest are not within the [contract area].”

The protest lasted three days and ended when police arrived on the third day.

Misapplication of US$6,000

Clarke and the protesters also demanded accountability for a US$6,000 CCC paid to the community forest leadership. The company had deposited the money into the community’s account.

Askew Varney, CCC’s bush manager, confirmed the company deposited the fund.

“My boss called and said the money given to the community had been mismanaged. I expected the [community leaders to meet] to say, ‘This is what the company has brought to us.’ There is no awareness going on. So, if they are going on with the protest they are right,” Varney said.

But instead of spending the money on community forest guards and health benefits, Mavasagueh’s leaders bought motorbikes and pills, according to Stephen Horace, one of the leaders. Horace said he had not seen the money but confirmed it had been misapplied.

Last week, at a Buchanan meeting to mediate between the protesters and the company, Representative Clarence Banks of Grand Bassa Electoral District Two and Superintendent Karyou Johnson suspended Mavasagueh’s leadership.

However, Representative Banks and Superintendent Karyou do not have any legal power to suspend the leadership. That power lies in Mavasagueh’s community assembly, its highest decision-maker, and the FDA. The FDA did not immediately respond to queries.

Isaac Tukar, Mavasagueh’s leader, denied any wrongdoing. “I am not in the know of any suspension,” Tukar said. “I am in the Guehsuah Section and doing my work.”

Representative Banks, told Okay FM, a DayLight affiliate, Vambo was awaiting the outcome of a three-week ultimatum CCC to address the protesters’ concerns.

“It is my citizens, that closed the roads. Give me three weeks, I will work with the Superintendent,” said Banks. “If the company does not listen to the issues that will be raised, “I will close it down legally.”

[Additional reporting by Ojuku Kangar]

This story was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).