Top: A drone picture of dredges on the River Gbeh in Sinoe County in 2024. The DayLight/Derick Snyder

By Emmanuel Sherman

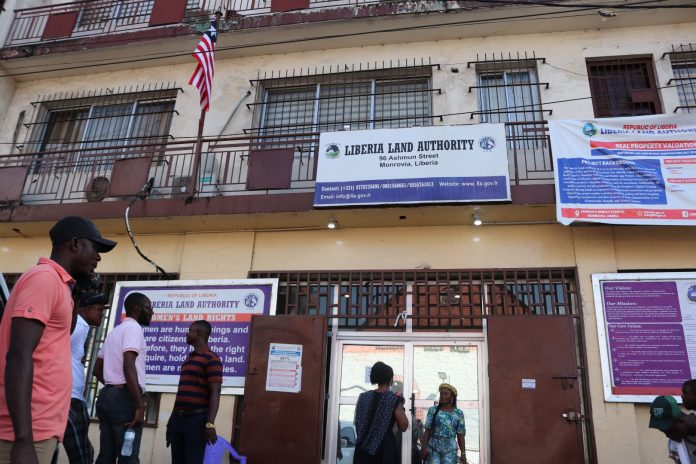

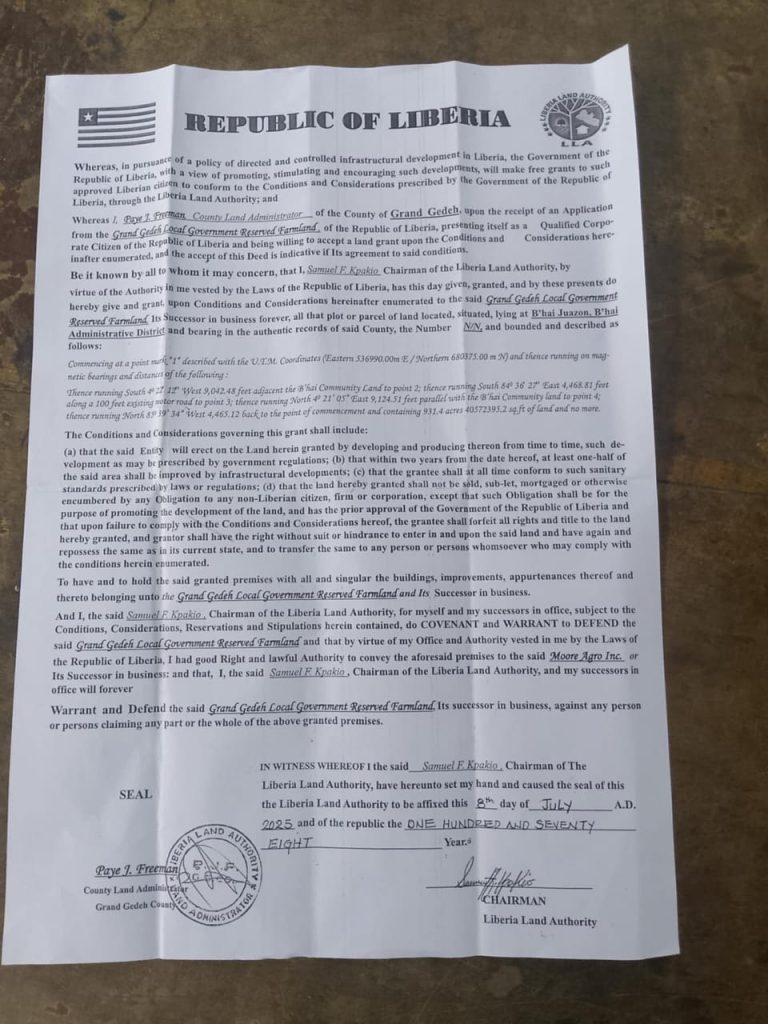

MONROVIA – The Liberian government has introduced permits for dredging on the country’s watercourses, six years after the machine was banned due to its negative impacts on people and the environment.

In 2019, the Ministry of Mines and Energy banned dredging for gold and diamonds as part of a reform of the artisanal mining subsector.

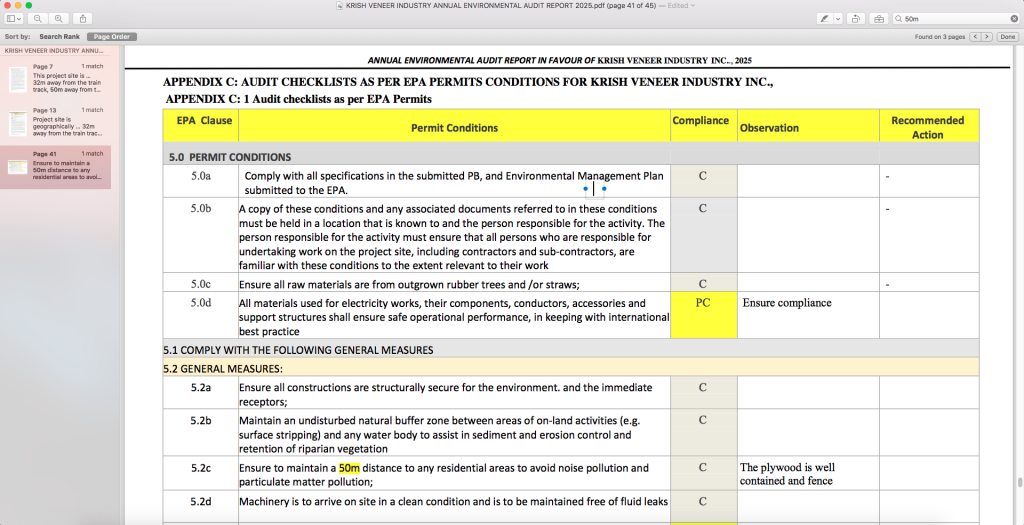

But based on a new fee structure published in June by the Ministries of Mines, and Finance and Development Planning, small-scale gold and diamond miners now pay US$1,500 for a dredging permit, and medium-scale miners US$10,000. The Ministry even introduced a permit for ocean sand dredging, which costs US$60,000.

Minister of Mines Matenokay Tingban did not respond to detailed queries despite weeks of engagement.

Ex-Minister of Mines Wilmot Paye, who introduced the permits four months before his dismissal, defended his actions. Paye said the permits were necessary to regulate dredging and position Liberia to maximize benefits from potential critical minerals in the ocean.

“Dredging, like excavator use, should only be used under a permit. That is why the turbidity of our rivers is disturbed,” Paye told The DayLight.

“Because of their unique nature and applications in mining operations involving riverbeds, the use of dredges must be controlled. In short, an operator should first obtain a permit to use a dredge. Before a permit is issued, as in all other instances, technical conditions must be satisfied.”

“The scramble for raw materials is taking humanity far beyond the earth’s crust,” Paye added.

The policing of dredging activities adds to the many problems the Ministry of Mines faces in regulating a sector plagued by illegal activities for decades. A 2021 GAC report found that it lacked a trained workforce, did not have tools for monitoring, and had decreased revenue. The country loses millions of United States dollars to illicit activities.

Liberia’s stance on dredging is the complete opposite of Ghana’s. Dredging has been one of Ghana’s biggest issues over the past decade, with demonstrators earlier this year calling for a state of emergency to fight “galamsey.” Earlier this month, the country repealed a law to protect its forests from illicit extractions.

Social and health issues

In his turnover speech last month, Paye said the dredging of other permits he introduced would boost Liberia’s revenue generation. Mining is one of the main drivers of Liberia’s economy. The sector generated over US$121 million in 2023, according to the Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

But Emmanuel Swen, an ex-Assistant Minister for Mines, who helped impose the ban on dredging in 2019, urged the government to reconsider its decision.

“I think the decision was informed by revenue generation, and not based on environmental and health considerations,” Swen told The DayLight. “It is not advisable to use dredges, especially those used by local miners, artisanal, and small-scale operators.

“I think it is something that should have been looked into further because it involves a lot, especially with respect to environmental implications,” Swen added.

Like Swen, environmentalists and campaigners are critical of dredging. Dredging pollutes water, destroys aquatic habitats, and threatens the tourism industry, according to environmentalists. A dredge removes sediments from the bottom or banks of bodies of water, including rivers, lakes, and streams. It creates a vacuum to suck up and pump out the unwanted sediments and debris.

Dr. Eugene Shannon, an environmentalist and former Minister of Mines and Energy, further broke down the harmful implications associated with dredging.

“When the sea and river beds are dredged, the nesting grounds are destroyed, and fish migrate,” Dr. Shannon said.

“Ocean Sand mining is more erosive because of the… destruction of the coastal reefs and the deep-sea bed nesting environment,” said Dr. Shannon.

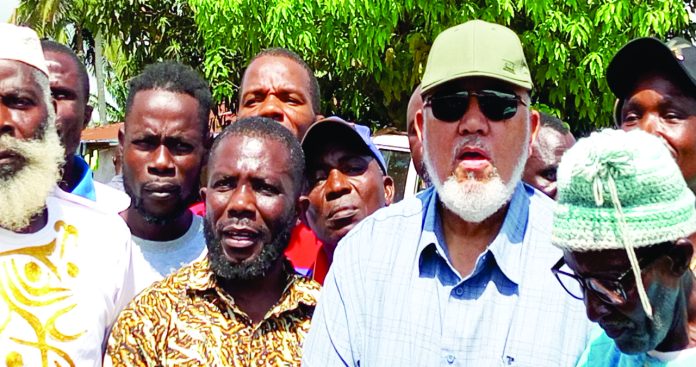

The Federation of Miners Association of Liberia, the largest and most influential of such groups, said it had no clue that dredging had been legalized.

“As representatives in this sector, we were not consulted,” said Abraham Gappie, the federation’s acting president. “It has great environmental, social, and health issues for the miners, the mining community, and even areas where people are not mining.”

Last year, the EPA warned about the overuse of mercury in Liberian waters related to dredges, which persisted nationwide even amid the ban.

Dr. Emmanuel Yarkpawolo, EPA’s Executive Director, told a Ministry of Information press briefing called for a collaboration among the EPA, county authorities, and local people.

“Unregulated, unsustainable, and unreported extraction of our natural resources in a crude manner that continues to destroy and degrade not only our land areas, but also major water bodies,” Yarkpawolo said.

Six months later, President Joseph Boakai imposed a moratorium to protect wetlands, waterways, and beaches against encroachment and pollution.

Integrity Watch Liberia provided the funding for this story. The DayLight maintained complete editorial independence over its content.