Top: Men make a dredging machine on the Zormue Creek in Bokomu District, Gbarpolu County after Weedor Gee, the owner, obtained clearance from the local representative of the Ministry of Mines. Picture credit: Korninga A Community Forest

By James Harding Giahyue

ZORMU, Gbarpolu – Illegal miners are set to dredge a sacred creek in a town in the Bopolu District of Gbarpolu County.

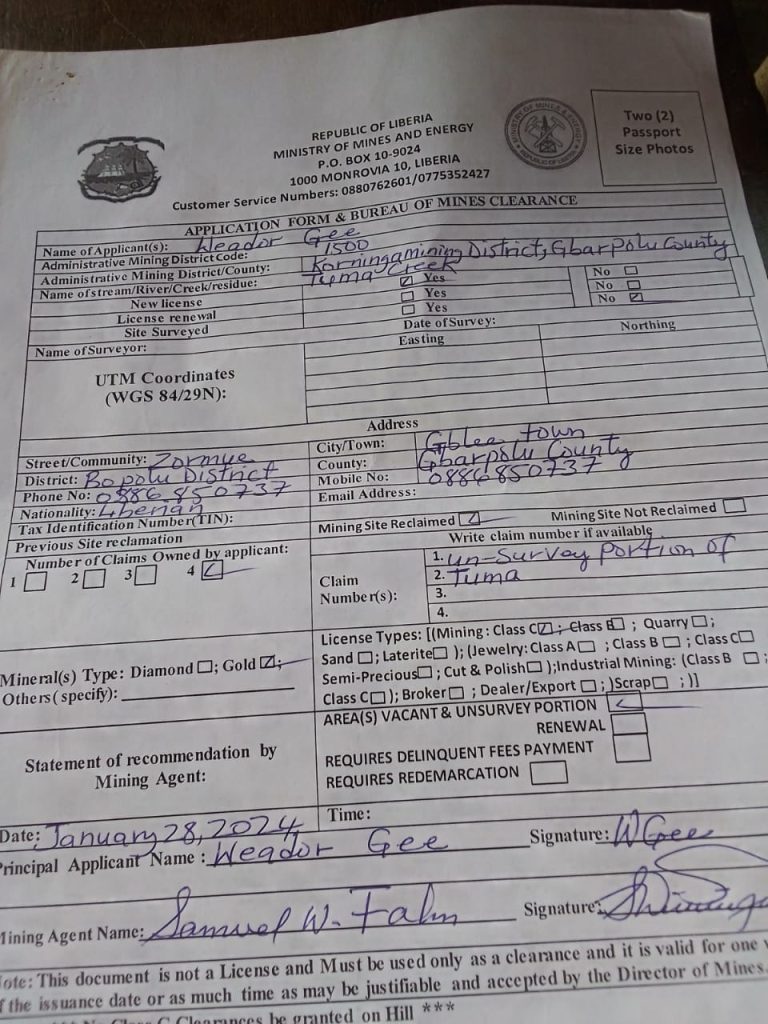

The miners who work for Weedor Gee, a businesswoman who hails from the region, built dredge on the Tumu Creek. Gee has no prior history of holding a mining license, records of the Ministry of Mines and Energy show.

Tumu Creek is revered in the Korninga Chiefdom, and it is a sacrilege to even put a canoe over it without a traditional rite, locals say.

Initial videos and photographs obtained by The DayLight show the miners building the machine. Others taken a week later reveal two miners assembling the makeshift machine on the creek, ready to operate.

In 2019, the ministry imposed a moratorium on dredging nationwide. The suspension, which is still in place, was meant to curb the pollution of water bodies across the country and the degradation of the rural environment.

But the dredging and other forms of illicit mining continue to proliferate in remote regions, polluting streams and threatening local traditions.

Samuel Fahn, the mining representative in the region, had issued Gee a clearance late last month. Gee paid Fahn US$400 for the clearance, with both of them confirming the transaction.

Clearance fees for mining agents are not legal but are accepted by authorities. An outgoing official of the ministry, who asked for anonymity, said it was meant to empower mining agents to function.

The leadership of the Korninga A Community Forest, in which the creek is located, raised qualms about the dredge, based on the videos and pictures.

“The document says class C but the materials they are carrying are for dredging,” said Emery Ciapha, the acting chairman of the Korninga A Community Forest.

“I know that the… Ministry of Mines and Energy is not offering a license for dredging in this country,” Ciapha added in an interview in Tawalata Town. He said he would monitor the situation “closely.”

Gee said in a phone interview that dredging would keep illicit miners away. “We want to stop people from invading our farmland, that is the main issue that carried me there,” she said.

“It is just to stop people from [encroaching on] the land because if a person gets a license, you cannot stop them from doing what they want to do.

“If you have the land and get a claim, you can do what you want to do with it,” Gee added.

Gee disclosed that she had thought about farming but changed her mind to mining based on someone’s advice. She decided to dredge because it produced quicker results than mining on the land or the banks of the creek.

A dredge uses a vacuum to suck out mud and debris from the bottom of a water body. Then a water pump removes unwanted sediments and traps gold nuggets on a slanted platform. The process involves less labor but pollutes the water environment and makes it inhabitable for fish, experts say.

Fahn denies authorizing the businesswoman to dredge the creek. “I did not tell them to use dredge. If I come and see anyone mining with dredge, I will close them down,” he told The DayLight. Fahn had made those comments about a week before The DayLight obtained evidence that Gee built the dredge.

Gee refutes Fahn’s claims, though. She counterclaims that he was aware of her intent to dredge the creek from the beginning. She failed to provide any evidence to back that claim.

“Each time he goes there, he asks, ‘Where is the [dredge’s] key?’

“We say, ‘Here is the key. We are not working. “He says, ‘Are you working?’ We say, ‘No, we are working.’” Gee said she did not know dredging was outlawed and Fahn did not inform her.

Fahn did not answer calls for a reply to Gee’s comments and he did not return the call. However, Fahn said in his original interview that the creek was mentioned so that Gee’s mineworkers could work on the banks of Tumu Creek.

The clearance also appears to vindicate him. The document marks class C as the license type. Multiple sources familiar with the industry said Fahn mentioned the creek to locate the claim, not to authorize dredging.

Asked about her relationship with traditional authorities, Gee said she had the support of chiefs and elders as their daughter.

George Ballah Sumo, the Paramount Chief of Korninga Chiefdom, denies that claim.

“Nobody has met up with my office about dredging,” Sumo said. “I will not allow people to dredge on that water because it will destroy the water source.”

Sumo said the community would only accept a medium or large-scale mine there to build its road network.

Mining on a sacred site without the authorization of local chiefs and elders is prohibited under the Minerals and Mining Law.

Funding for this story was provided by the United States Embassy. The DayLight maintained editorial independence over the story’s content.

Facebook Comments