Top: Graphic showing FDA Managing Director Mike Doryen and different illegal activities of West Africa Forest Development Incorporated (WAFDI) in Grand Bassa County. The DayLight/Rebazar Forte

By Emmanuel Sherman

GONO TOWN, Grand Bassa County – At the end of 2021, the Ministry of Justice concluded an investigation into a Chinese-owned company accused of illegal logging.

The investigation confirmed that the West African Forest Development Incorporated (WAFDI) harvested logs in the Gheegbarn #1 Community Forest in excess of legal requirements. However, the investigation found WAFDI was not alone.

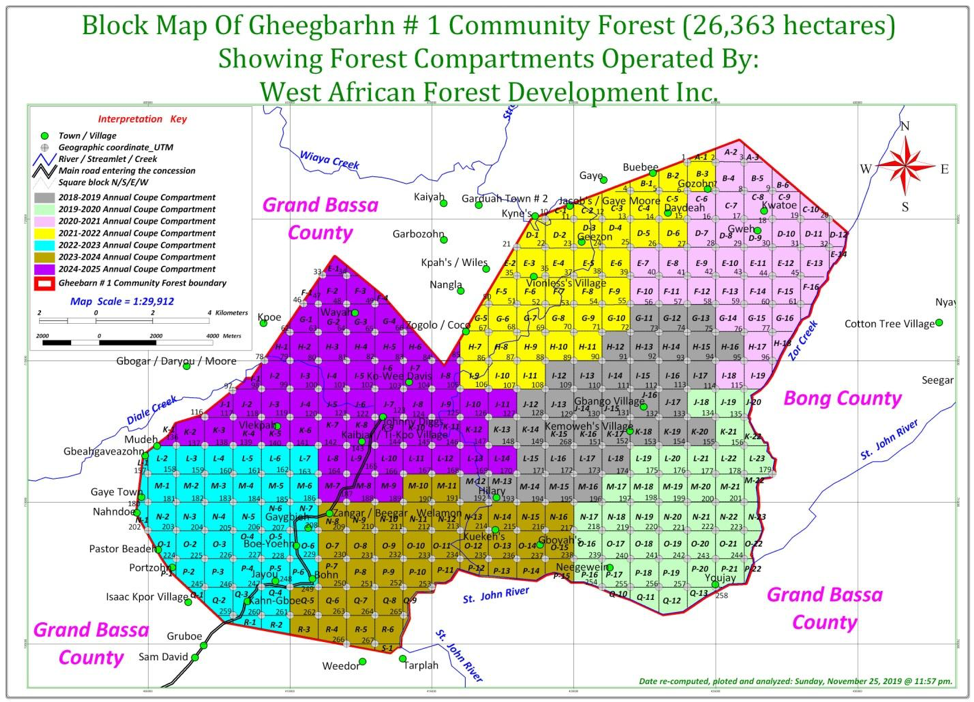

It turned out, the Forestry Development Authority (FDA), which had recommended the official inquest, had illegally awarded WAFDI about 14,460 hectares of extra woodland in Grand Bassa’s Compound Number Two. The agency had approved Gheegbarn’s entire 26,363 hectares to be harvested over two times faster than normal forestry regime demands.

What happened in Gheegbarn was the peak of illegal logging activities in at least seven community forests in four counties. It could be the biggest logging scandal after the FDA illegally awarded about 2.5 million hectares of forestlands to companies over a decade ago.

‘We hereby approve…’

It all began in December 2018 when WAFDI signed a seven-year agreement with the leadership of Gheegbarn #1. (They call it that way to distinguish it from Gheegbarn #2, a neighboring community forest). WAFDI is owned by a Chinese named Wang Chenchen. It has a link with Augustine Johnson, the manager of Mandra, an Asian-owned company the FDA recently penalized over its abandonment of thousands of logs.

One year on, WAFDI presented the FDA with its harvesting blueprint for five years, known in the industry as a forest management plan. Then it broke down the plan into seasons.

Season 2018-2019, the first, targeted about 3,700 hectares, the documents show. The other plans featured larger harvesting areas, including about 4,000 hectares for the season 2024-2025, according to The DayLight’s estimate.

The FDA confusingly illegally approved WAFDI’s plans twice, first on July 4, 2019, and then on August 26, 2020, according to official documents.

“We hereby approve said plans having met all basic requirements,” FDA’s Managing Director Mike Doryen said in communications to the company. It ironically hyped the plans for being “complete,” “accurate” and containing “quality information.”

“Therefore, management anticipates full compliance in the implementation of these plans as we strive to ensure sustainable forest management in Liberia,” the letters added.

Plans approved, WAFDI began to operate in 2019, according to official records.

But barely two years later, the FDA disapproved of WAFDI’s attempt to export 601.801 cubic meters of logs. The FDA accused WAFDI of harvesting timber in forest areas it had not permitted.

Later on, the FDA asked the Ministry of Justice to investigate, which it completed in about two months. SGS had reported the matter a month earlier in a monthly publication.

By that time, WAFDI had harvested 6,007 or 32,347.855 cubic meters of logs, according to the Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (LEITI), citing FDA and company records. It exported some 29,104 cubic meters. In 2021 alone, WAFDI sold US$531,460, LEITI records show.

The investigation did more than book WAFDI over the embattled swathe of forest. It found that the FDA was largely responsible for the situation.

“The investigation found that other logs from the purported unapproved blocks were previously approved and export permits were signed by the FDA… and SGS,” Minister of Justice Frank Musa Dean wrote to Harrison Karnwea, the chairman of FDA’s board of directors, on December 2, 2021.

“WAFDI took advantage of [FDA’s illegal approval] and requested to commence operations and same was granted by FDA beginning 2019,” Dean’s letter further read.

It said FDA and SGS had sanctioned the company’s harvest and export under the very illegal plan FDA. SGS is a Switzerland-headquartered firm that helps track Liberian logs from their sources to final destinations.

The FDA broke the law in the first place by approving the company’s plan to harvest all 26,326 hectares in seven years, the investigation found. The National Forestry Reform Law requires the FDA to monitor all harvests and ensure they are legal and sustainable. The Code of Harvesting Practices, on the other hand, restricts the rate of felling trees to 15 years.

The investigation unearthed FDA had endorsed the WAFDI-Gheegbarn deal to last for seven years, instead of the 15 years in the Community Rights Law of 2009 with Respect to Forest Lands.

The DayLight’s review of the illegal harvesting plan showed FDA awarded all of Gheegbarn’s 26,326 hectares in just seven years. The regulator further okayed the company to operate somewhere between 3,700 and 4,000 hectares. That was more than doubled the forest area the code requires.

Overall, the FDA granted WAFDI an area in excess of 14,460 hectares of humid, Bassonian forest, according to our calculations. And by the time of the ministry’s inquest, WAFDI had already harvested 11,600 hectares an unlawful bonus of 6,500 hectares. That means, in less than three years, WAFDI cut trees which would have taken seven years to do legally.

WAFDI was not the only company in the scandal. Within that same period, the FDA illegally approved six other agreements in Grand Bassa, River Cess, Nimba and Gbarpolu.

Like WAFDI, the FDA authorized the companies to harvest all of their contracted forests within the duration of their agreements.

The scandal mirrored another one in Zorzor, Lofa County, where the FDA permitted a company to harvest an estimated US$2 million worth of logs outside its contract area. The FDA replaced its staff who supervised the county at the time.

‘Restore the Sanctity of the FDA’

The Ministry of Justice urged FDA’s board to take action against individuals “to restore the sanctity of the FDA.”

The board of directors heeded the ministry’s advice. It passed a resolution on January 26 last year, calling for the dismissal of Jerry Yonmah and Simulu Kamara, the technical managers of the commercial and legality verification departments, respectively.

The resolution also called for the dismissal of Abraham Sheriff and Jessie Vannie, the operations and data information managers of the legality verification department, correspondingly. They deny any wrongdoing.

Five days after its resolution, the board asked President George Weah to sack and retire Joseph Tally, FDA’s Deputy Managing Director for Operations. The board accused Tally, who the resolution listed, of aiding in the illegalities.

“This will send a strong message to would-be violators,” Karnwea’s letter to President Weah read. It said the scandal had “eroded the credibility of the management team, thereby affecting donors’ behaviors.”

Though the resolution spared Doryen, who approved all of the illegal documents, he was clearly reprimanded. The resolution advised him not to sign any future documents without the counsel of the FDA’s legal department and that he must attend important meetings to be abreast with forestry matters.

President Weah did not heed the board’s recommendation and Tally remains in his position. Tally told The DayLight in June the matter was now “water under the bridge,” praising “dynamic” and “prudent” President Weah for retaining him.

Also, none of the accused masterminds was fired. However, they were all replaced, giving way to new heads of the commercial, legality and community forest departments.

The Aftermath

In the end, WAFDI’s agreement with the villagers was amended from seven years to 15 years. Subsequently, work in Gheegbarn ceased for about 11 months. It was unclear whether the FDA and WAFDI corrected its harvesting plan as the Ministry of Justice had instructed. The FDA did not grant The DayLight’s request for that and other documents, a violation of several forestry legal instruments.

As the scandal shook the FDA to the core, it took a toll on Gheegbarn.

In their agreement, WAFDI promised to build roads, schools, a clinic, and latrines, construct handpumps, and pay scholarship fees. However, the company has not met its obligations.

“They are using the halt as an excuse to not do our projects,” said Junior Wesseh, the head of the community leadership. “They have been operating for five years, only two handpumps and a latrine they dealt with.”

Apart from community projects, the company also failed to pay harvesting fees before its operations ceased.

“They said they were not responsible for our cubic meters fee, because they lost US$1 million dollars,” said Larry Tuning, the secretary to the community leadership.

Based on The DayLight’s calculations, WAFDI should pay Gheegbarn US$64,695 for the logs it produced from 2019 to 2021, at least according to official data. We could not independently verify Tuning’s claim in the absence of payment records. By law, WAFDI and the FDA should have published the figures in the newspapers and the agency’s website.

WAFDI called off an interview with The DayLight in its third minute upon Johnson’s orders. Johnson said the newspaper had not given prior notice. He did not respond to emailed queries afterward.

But responding to criticisms from Gheegbarn’s leadership when the European ambassador visited the area in March, Gualberto Ojo, a WAFDI representative, blamed the company’s indebtedness and failures on the U.S-China trade war and illegal chainsaw milling. The ambassadors had chosen the region as a case study to understand the challenges of community forestry.

Ojo—and the FDA managers present—avoided talking about perhaps forestry’s biggest scandal in the last decade.

The FDA did not return The DayLight’s queries for comments.

This story was a production of the Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).

Facebook Comments