Top: Different sections of the Invincible Sports Park. Picture credit: Knewsonline

By Gabriel M. Dixon

Monrovia – It illuminates the open landscape of the runway of the James Spriggs Payne Airfield. It is coated in sparkling green with courts for basketball, tennis, and volleyball, a small playground and a parking lot. It even contains a museum that pays homage to the glittering football career of President George Mannah Weah. The Invincible Sports Park is a marvel of recreational beauty.

But an investigation conducted by The DayLight shows the park breaches international aviation standards. It is right within the runway end safety area (RESA), which is the area beyond the end of a runway that is meant to reduce damage to aircraft when picking off or landing. The area enhances the safety of airplanes and it provides greater accessibility for firefighting and rescue equipment during airport incidents.

“An object situated on a runway strip which may endanger aeroplanes should be regarded as an obstacle and should, as far as practicable, be removed,” according to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a UN body that sets global standards for the aviation industry. In aviation, the runway strip is the combination of a runway and the runway end safety area.

“No fixed object, other than visual aids required for air navigation or those required for aircraft safety purposes and which must be sited on the runway strip,” the ICAO recommendation continues.

Though the safety area of the airport does not meet ICAO’s recommended standard of 240 meters, it met the mandatory minimum standard requirement of 90 meters. However, that dimension has now been reduced.

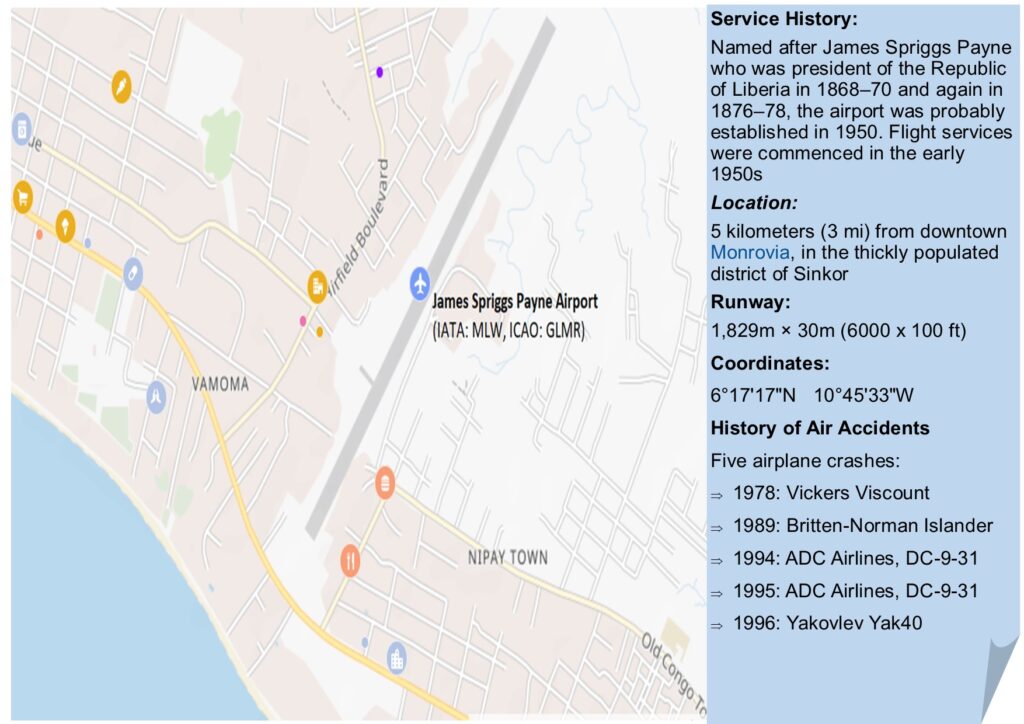

The spot at which the Invincible Sports Park now sits is infamous for aviation accidents, further raising concerns about its safety. In August 1994, a Douglas DC-9 belonging to ADC airlines carrying 82 passengers and 9 crew members, crashed exactly at the spot while landing. Four other plane crashes are associated with the airport: another ADC airliner in 1995, one in 1996 and two others earlier on in 1978 and 1989.

President Weah is firm that his decision to construct the glamorous park in the safety area of the airfield despite the location’s tragic history. He told the opening ceremony of the park last week the project had claimed his attention to repairing the airport.

He said: “I have therefore directed the Liberia Civil Aviation Authority (LCAA) and the management of the airport to draw up plans and to develop a feasibility study for the upgrading of this facility, including the extension of the runway in the direction of the swamp, in order to enable international jet traffic to operate from Spriggs, and the construction of a new access road for both passengers and cargo.”

Weah might have justified the controversial location of the park. However, he opened another Pandora’s box regarding safety and the environment. Expending the runway strip into the mangrove swamp would violate Liberia’s Environmental Protection and Management Law. The law prohibits people from building in wetlands. Furthermore, the swampland the President spoke of is part of the Mesurado Wetlands, which is a protected area under the Ramsar Convention, an international treaty that protects such environments worldwide. Wetlands serve many purposes, including a buffer against storms, a nursing ground for aquatic species and a hideout for endangered species. The Liberian government will have to show the project would not have a negative impact when that time comes in accordance with the law.

At the start of the park project last year, President Weah had said that the park had “no interference with the airport. The plane will come, the plane will pass, [and] the plane will land,” Weah said in a viral video posted to Facebook in December last year.

Weah even argued against the commercial status of James Spriggs Payne Airport in that post. “Even the airport they talked about, [planes] come here every five years. It (the James Spriggs Payne Airport) is not a commercial airport. So, here we are, it has nothing to do with the airport,” he said.

Contrary to the President’s claims, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Air Transport Association (IATA) regard the airport as suitable for commercial flights and the only other paved runway in Liberia, second only to the Roberts International Airport. Spriggs Payne Airport handled limited international flights despite safety concerns during the war. Scheduled commercial flights resumed in 2008. The airport underwent a major renovation in 2012 and began commercial flights under former President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf. Elysian Airlines and ASKY Airlines provided services from Monrovia to Banjul, Accra, Freetown, Lagos, and other West African cities. But these small carriers have since stopped flying to Liberia due to airport safety concerns. Mission Airlines Fellowship (MAF) currently uses the James Spriggs Payne Airport for domestic flights.

The Liberian Senate unanimously voted against the project due to safety concerns but later rescinded its decision and approved the project.

The park is the latest twist in a long tale of how successive governments have handled safety standards at the James Spriggs Payne Airport since its establishment in 1950. Situated in the densely populated district of Sinkor, three miles from central Monrovia, it has had its own share of the ineptitude of the Liberian political landscape.

In the late-1970s, President William R. Tolbert, Jr opted to improve the facility. The government at the time erected a metal fence and barred unauthorized access in a bid to keep it compliant with international best practices. It conducted a feasibility study and planned relocation of adjacent communities, including Wroto Town, Lakpazee, Tweh-Johnsonville and Key Hole. But that plan never happened, as he was overthrown about this same time in 1980 by future President Samuel K. Doe.

It was during the regime of President Doe that football became a feature of the airfield. The metal fence erected by his predecessor was vandalized and looted. It became a practice ground for the Invincible Eleven Football Club (IE), with whom, Weah began to ply his trade to international superstardom. Not just football, the airfield was misused, as it became a major footpath that connected the Sinkor communities of Airfield and Old Road. It was sued for open defecation and a dumpsite.

Peacekeepers of the Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) did not help the situation. The airport became a military target for Charles Taylor’s rebel forces. In 1992, the airport was hit multiple times by rockets that destroyed dozens of aircraft and damaged its runway and terminal station.

Those abuses continued during the regime of President Charles Taylor, who closed down the airport in June 2002, on grounds that it was close to his Congo Town residence.

In 2012, the administration of President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf erected a concrete fence around the airport and basic rehabilitation works were completed to bring it to international standards. A signboard at the current location of the Invincible Sports Park brandished the inscriptions: “No Flying Kites” and “No Playing Football.”

Facebook Comments