Top: A community in the Yarmein Clan in Nimba County the Land Authority has issued a deed, according to a new report. The DayLight/William Harmon

By James Harding Giahyue

MONROVIA – Before the Land Rights Act of 2018, chiefs and elders across Liberia issued thousands of tribal certificates to individuals as a kind of title to lands in towns and villages. But in many cases, the chiefs did not consult other members of the communities, among other things, making tribal certificates arguably the most troublesome subject in Liberia’s land reform process.

To address this problem, the law requires tribal certificates to be legally processed into deeds with the involvement of full membership of communities—men, women and the youth—that own the lands for which the documents were issued. The Liberia Land Authority (LLA) is yet to formulate regulations for the implementation of the law, including the vetting of all tribal certificates.

But the LLA has issued tribal 11 deeds to individuals and a community in Bomi and Nimba from tribal certificates in the absence of regulations, a new report by a conglomerate of civil society organizations has found.

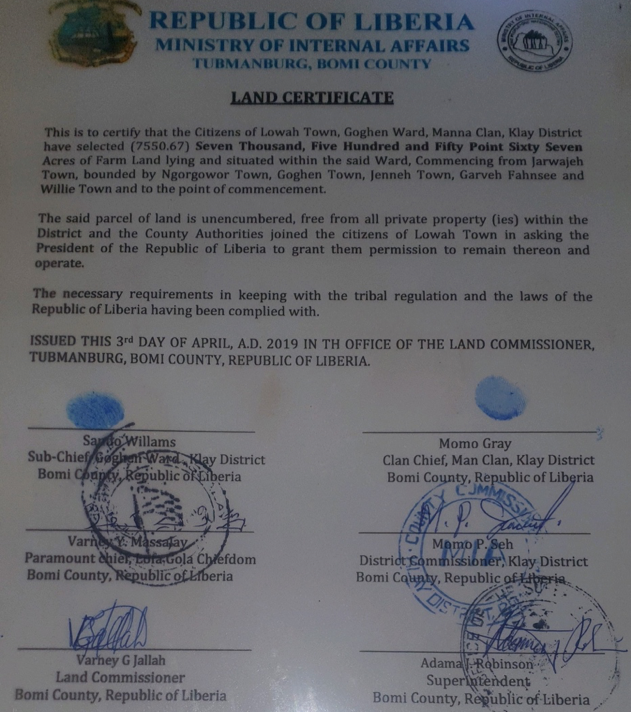

In their report late last month, the Civil Society Land Reform Working Group (CSO-LRWG) revealed that the Land Authority has issued 10 deeds to people in the Yarmein Clan of Nimba from tribal certificates and one each to Lowah Town in the Klay District of Bomi County.

Several provisions of the law call for the Land Authority to formulate regulations for the “effective implementation of the act.” The law reads in its 12th article, “The right to the ownership and use of Land is not absolute but is subject to reasonable regulations.” The LLA said last year it had begun the formulation of the regulations but has not completed it, more than three years after the passage of the law.

“The Land Authority is violating the very law it was created solely to implement,” said Daniel Krakue of Social Entrepreneurs for Sustainable Development (SESDev), one of the organizations that published that report.

The report urged the LLA to nullify all deeds it has issued from tribal certificates, halt the processing of the documents until it completes the regulations, and restitute fees communities and individuals have paid. It called for an inquest into fees being charged for customary-land surveys as well as the prosecution of culprits.

The report comes at a time when 170 communities are awaiting the LLA to conduct its confirmatory survey to get their ancestral land deed.

The LLA said it would respond to the report at a later date.

In its investigation, CSO-LRWG said it interviewed townspeople of the two communities in the counties, held workshops for 47 people in two weeks in December last year. Other than the relevant tribal certificates, it said it reviewed several documents related to the communities, such as deeds, receipts and letters. Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI), an international nongovernmental organization that focuses on land tenure and forestry, funded the report. CSO-LRWG comprises 33 local groups, which campaigned for the passage of the historic law, hailed across the world for its recognition of ancestral land rights.

Tribal Certificate Amid Moratorium

Having processed without any existent regulations, the tribal certificate from which Lowah’s deed was granted was issued to the community in 2019 amid a moratorium on the sales of all public lands across the country, the report said. The deed, seen by The DayLight, was signed in October last year by Atty. Adams Manobah, chairman of the Land Authority, covering 1,777.1 acres of land in the Mannah Clan. President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf issued the moratorium in 2013 as land crises spiraled out of control, and the ban has not been lifted.

‘“The validity of tribal certificates shall be determined by a rigid validation process involving the community conducted by the Liberia Land Authority,”’ the report said, quoting a provision of the Land Rights Act. “It reminds unclear on what condition the Liberia Land Authority issued a customary statutory deed to Lowah Town.”

Varney Jallah, the land administrator of Bomi County, who signed Lowah’s controversial tribal certificate, admitted to that but said it was not official, and that he had signed the document under pressure from the townspeople.

“Our people get problem. When they came for the tribal certificate, we told them that ‘Even if you have a tribal certificate, it will just be for formality,” Jallah told The DayLight in a mobile phone interview on Thursday. “Even if we give you this, it is not by law. I was clear with them but they said no.

“If you are working in a community, especially traditional communities, you will explain some things, you will go up and come down, they will say X, Y, Z,” Jallah said, adding that the Lowah’s tribal certificate was nullified and still made to go through the legal steps provided in the law before obtaining its deed. Communities first identify themselves as landowners and organize and create bylaws, demarcate their boundaries with neighboring communities.

The report also criticized the Land Authority over its “astronomical” fees for the survey. Lowah paid L$132,900 (approximately US$700 in 2019) for its survey, captured on the community’s deed. Lavekai, another town in the same district, paid US$2,000 in September for the same purpose, according to the receipt of that payment.

CSO-LRWG had in June last year disapproved the Land Authority’s proposal to charge communities an “appropriate, reasonable facilitation” instead of a fixed affordable charge to avoid corruption. The report said the Land Authority was yet to get feedback on their recommendations.

“Customary communities are paying huge prices just to secure full ownership rights to their customary land, support their livelihood and sustain their cultural heritage,” the report said.

The report said the 10 people in Nimba County who received deeds already had a lease agreement with ArcelorMittal, based on their tribal certificates, some of which The DayLight has seen.

Eddie Beanjar, Sr., the land administrator of Nimba County, denied that the deeds had been issued, clarifying that the individuals were at the verge of getting legal claims to their respective plots of land.

Facebook Comments