Banner Image: Liberia promised to reduce deforestation by 50 percent. The DayLight/James Harding Giahyue

By Varney Kamara

In December 2015, 196 countries across the world met in Paris, France, to take uniform action in addressing the effects of global warming. The Paris Agreement or COP 21 is an internationally binding legal treaty whose overall goal is to reduce global carbon emission to well below 2.0 degrees or preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels.

Liberia was one of those 196 signatories. The country made a commitment to reduce its economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions by 64 percent below the projected business-as-usual (BAU) level by 2030.

Ahead of the COP26 Glasgow climate change conference, the country took a step toward its implementation plan. In July this year, Liberia revised its nationally determined contributions (NDC) document and pledged to mitigate the effects of greenhouse emissions in various sectors, ranging from agriculture to waste management. Here are the things Liberia promised the international community it will do to reduce the effects of climate change:

Agriculture

In the agriculture sector, Liberia committed itself to lower greenhouse gases emissions related to agriculture and livestock systems by 40 percent below BAU levels by 2030. It said it would achieve this target through the promotion of low-emissions rice cultivation and reducing the burning of field residues. The country also promised to source funds and establish programs to promote low-carbon agriculture practices, including conservation agriculture, a farming system that promotes minimum soil disturbance (i.e. no digging), maintenance of a permanent soil cover, low digging, combined agroforestry systems, improved lowland rice cultivation, multi-cropping, organic fertilizers, a concept that relies on using existing irrigation systems, and the use of sustainable agricultural waste management, among others.

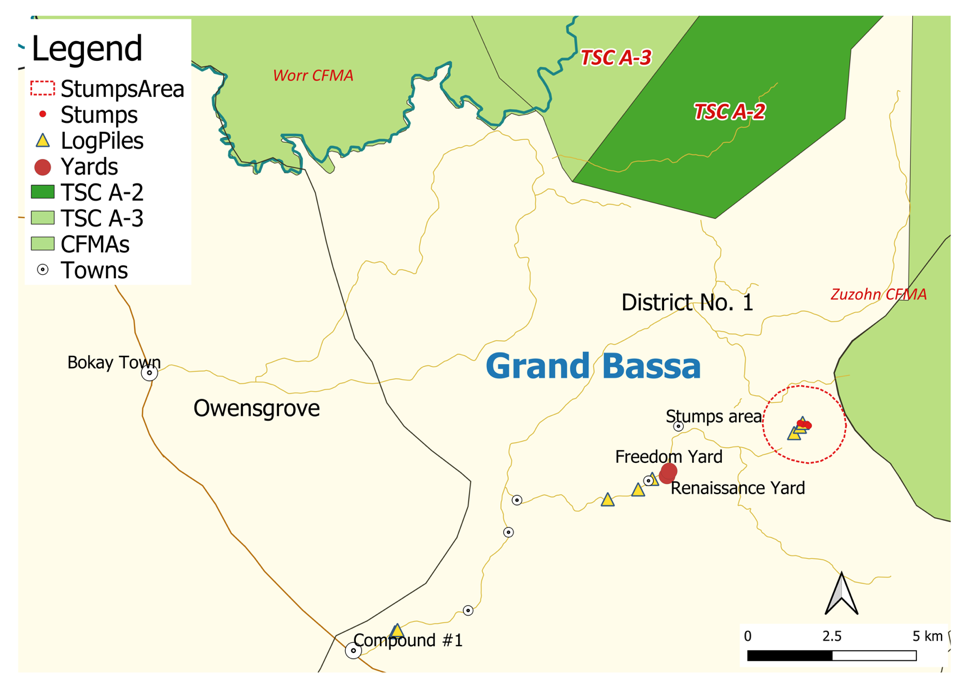

Forests

Liberia obligated itself to reduce GHG emissions by enhancing the natural environment to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in forested and marine areas, including a reduction of the national deforestation rate by 50% by 2030. The country said it is committed to decreasing emissions by clearing forests and creating grasses for cattle by 40 percent below BAU levels and reducing greenhouse gases by 5,147 Greenhouse gases and carbon dioxide (GgCO2e), and reforesting an average of 12,285 hectares per year to enhance forest carbon stocks by 1,013 GgCO2e. Its strategy is to invest in natural regeneration and tree-planting through community and school programs, including financing sustainable woods that are used for cooking, and charcoal production.

Coastal Zones

In the Coastal zones segment, Liberia assured the world that it will cut down GHG emissions from changing of natural ecosystems to agriculture as well as the abandonment of farmland, and enhance carbon sinks in mangroves and other blue carbon ecosystems, including advancing protection and conservation measures in 30 percent of mangrove ecosystems and reduce GHG emissions by a total of 1,800 GgCO2e through the protection mangrove ecosystems. Liberia also pledged to improve coastal carbon stocks that include mangroves, tidal, salt marshes, and seagrasses. The government said it will do this by restoring 35 percent of degraded coastal wetlands and mangrove ecosystems. It said it will expand marine and coastal ecosystem protection by establishing two marines and two coastal protected areas and developing new or updated protected area management plans. It said it will achieve these targets through the improvement of national policies, plans and investments to increase mangrove and coastal conservation and restoration, based on survey analysis of coastal zone ecosystems to identify threats and priority action areas.

Transport

In the Transport industry, Liberia promised to reduce GHG emissions by 15.1 percent below BAU levels by 2030. The country also vowed to reduce greenhouse gases and carbon dioxide by 16.9 GgCO2e. It also promised to introduce electric vehicles with a focus on private tricycles. It said it will reduce greenhouse gases and carbon by 32.3 GgCO2e by lending support to the transformation of the National Transit Authority (NTA) buses and private vehicles to compressed natural gas (CNG). The country said it will achieve these targets by introducing a vehicle labeling system, a feebate or rebate program through which the government levies fees on relatively high greenhouse gas-emitting vehicles and providing rebates on lower-emitting vehicles. It also said it will enforce a 10-percent tax on luxury vehicles and the integration of a tax on transit vehicles by 2025.

Energy

On the energy front, Liberia said it will reduce GHG emissions in this sector by 40.6 percent below BAU levels by 2030, creating a private investment enabling environment focusing on power purchase agreements (PPAs) for renewable energy (RE). The country said it will reduce emissions by 79.8 per year by installing 100 megawatts (MW) plants producing 300GWh per year with a load factor of 40 percent. The country said it will reconnect Monrovia clients to the grid, and decrease emissions by 124.15 per year by supporting the process by which 100 percent of the owners of individual generators will switch to the distribution network. It said it will achieve these targets by developing off-grid small hydropower plants (HPP) and on-grid ones via PPAs, including a reduction of emissions by 15.4 per year by installing a batch of several sites with 20 MW capacity; medium HPP with an output of 40 and with 50% baseload minimum for rural electrification and connected to the grid.

Waste

In the waste sector, Liberia said it will reduce its GHG emissions here by 7.6% below BAU levels by 2030, and vowed to lower greenhouse gases and carbon emissions by 25.63 GgCO2e per year. It said it will do this by supporting the implementation of a landfill gas recovery system on Whein Town Landfill by 2022. The country also promised to reduce emissions by 25.63 GgCO2e per year by supporting the implementation of a landfill gas recovery system on Cheesemanburg Landfill by 2025, and reduce emissions by 0.84 per year by supporting the development of small-scale recycling of organic materials of market waste with a production of 500 t each year. It said it will achieve these targets by strengthening institutional and legal institutions at national and municipal levels, including the consolidation of operational and financial management capacities at the community and institutional level for an integrated waste management system by 2025.