Top: Some members of the network’s leaders at the Second National Land Conference last month in Ganta, Nimba County. The DayLight/ Harry Browne

By Esau J. Farr

GANTA, Nimba County – Communities in rural Liberia seek a customary deed to their ancestral lands but are plagued by boundary disputes.

Now, a new group, the Southeast Regional Network of Community Land Development and Management Committees, has been established to help resolve border conflicts and enable communities to acquire deeds much faster.

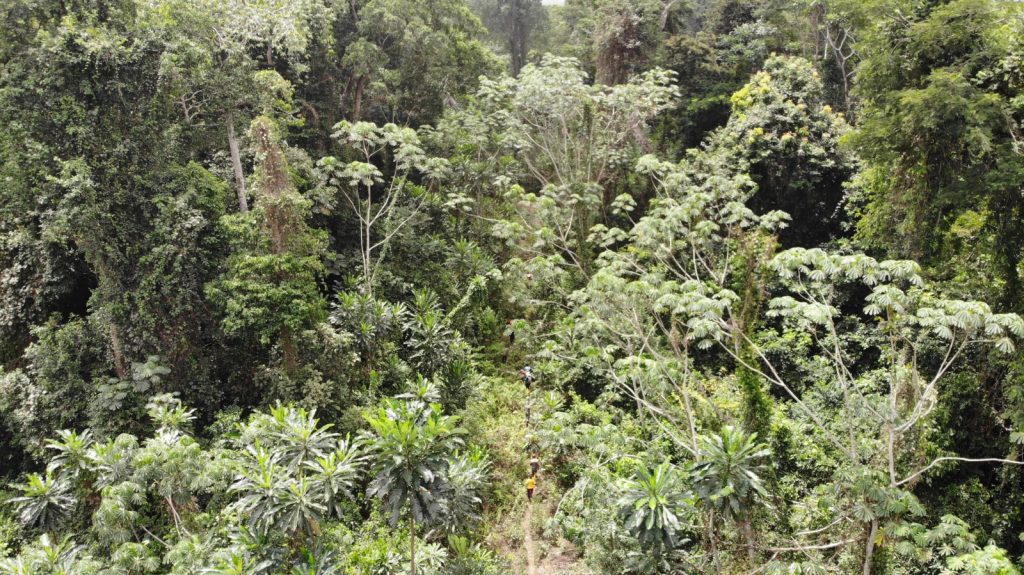

“We will identify the concerns and claims of communities, [and] involve the elders and traditional people for a peaceful resolution…,” says Augustine Dweh, chairperson of the network. Dweh spoke to The DayLight at the sidelines of the Second National Land Conference in Ganta last month.

“We understand that land disputes scare away development and that’s why we want to be serious about resolving disputes in our communities for us to live in peace,” adds Dweh.

Dweh’s community, Chedepo District, River Gee, does not have any dispute with its neighbors. However, several southeastern communities do. For instance, Lower Bokon, a clan in Sinoe’s Jaedae District, has had its quest for a deed stalled due to an issue with Neekleakpo, a town on the Grand Kru border.

Established this year, the network has more than 70 communities seeking a customary deed, according to the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI), the Margibi-based NGO that helped form it.

The Land Rights Act of 2018 gives communities ownership of customary land, but their ownership must be formalized by meeting certain requirements.

The process begins with locals self-identifying as a landowning community. They are required to create a bylaw and constitution, organize a governance body and cut boundaries with their neighbors. Then the Liberia Land Authority should conduct an official survey and present that community a customary deed.

The network also seeks to build its members’ capacity and increase awareness of land rights and issues.

Communities in Liberia heavily depend on over a dozen NGOs and development institutions to guide them through legal requirements for customary land deeds.

To date, 30 communities have been issued deeds, according to the Land Authority. In addition, 21 statutory deeds have been issued, 50 communities have completed the survey process, and five are waiting for their deeds.

There is a growing call for the Land Authority to fast-track the process, while NGOs criticize the regulator for prioritizing certain communities. The Land Authority blames the delay on poor funding and the lack of coordination with NGOs.

SDI helped form the network with funding from the US-based Rights and Resources Institute (RRI). The network intends to use peaceful traditional means to resolve existing and future boundary conflicts without the direct involvement of NGOs.

“Due to the absence of a regional and national body of the land sector, issues and challenges from the communities are difficult to handle or address,” says Daniel Wehyee, the coordinator of SDI’s community land protection program.

“The coming together of the communities will provide [them] opportunities to mobilize resources and strengthen its operations,” adds Wehyee. He says the establishment of the network presents an opportunity for community land rights actors to come together and champion their cause.

Last month, members of the network elected Dweh as chair, Mamie Freeman of Sinoe co-chair, and Jacob Nyamah of Maryland secretary general. Relevance Zeon of Grand Gedeh took the financial secretary position, while Tetoe Davis of River Cess and Anabel Sewon of Grand Kru clinched treasurer and chaplain, respectively.

The network seeks funding from national and international partners for the empowerment of its members at all levels. Lack of logistical support and funding to empower CLDMCs across the country delays customary land formalization processes.

“If we have bikes to visit our regional communities,” Dweh says, “it will help us settle boundary disputes to fast-track customary land formalization process.”