Top: Smith Sulonteh is claiming a portion of the Salayea Community Forest, including where he makes charcoal and planks. The DayLight/T. Prince Mulbah

By Prince Mulbah

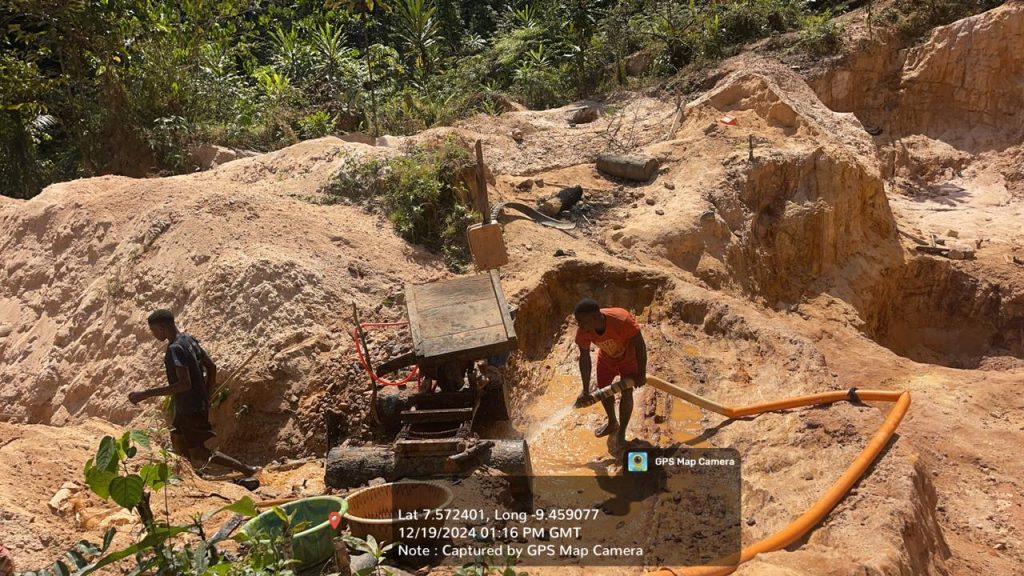

SALAYEA, Lofa County – Last year, townsmen were stunned when they discovered a huge pile of planks and the sound of a chainsaw deep in the forest in Gorlu during a routine patrol. When local guardians investigated, they found that a man was making planks and burning charcoal in the forest.

Angered by Smith Sulonteh’s actions, the community forest sued them at the Salayea Magisterial Court. It would turn out to be the beginning of a legal battle that has pitted the family against the community.

“We are managing this forest for the future generation, so we cannot allow a family just to come and claim the forest themselves,” said Yassah Mulbah, Salayea’s chief officer, outside of the courtroom.

“If they had their deed, they should have made it available during the establishment of the forest. The establishment of the forest was all on the radio; everyone knew about it,” added Mulbah. She was referring to a 30 or 90-day required period for a person with a private land claim to register their claim before a community forest is authorized.

However, Mr. Sulonteh said they decided not to make any claims at the time, based on their lawyer’s advice. He said their families purchased 2,244.27 acres or nearly 11 percent of the forest from chiefs and elders in 1967. He presented the families’ deed to the court, case files show.

“These people are claiming our land because they have few local authorities of Gorlu who are supporting them,” said Solunteh. If it is for this land business, they will kill me. I’m ready to die fighting for my rights, but our side is the law and the law is for everybody.”

Lawsuits

Salayea Community Forest was established in 2019, comprising six communities: Salayea, Yarpuah, Telemu, Gorlu, Ganglota and Beyan’s Town. It covers 8,270 hectares of rocky forestland in the Salayea, Lofa County, and is home to species, including monkeys, pangolins, and elephants.

Since its formation, Salayea has been involved conservation programs, including animal husbandry, village saving loan schemes, a mini-wood shop and Cocoa farming. It outlawed hunting, mining and other commercial activities.

Following Salayea’s lawsuit, the Salayea Magisterial Court imposed a stay order on Mr. Solunteh’s plank and charcoal. The court would later fine him for violating that order.

During courtroom proceedings, Mr. Solunteh presented a deed to the court to back his claim. The court handed the document to Salayea to verify at the Center for National Documents and Records Agency in Monrovia.

Mr. Solunteh disagreed with that judgment and filed a petition with the 10th Judicial Circuit Court in Voinjama to overturn the lower court’s decision.

The circuit court sided with Mr. Solunteh, according to the case files. The higher court reprimanded the lower court for not verifying the families’ deed itself, and for fining Mr. Sulonteh. The higher court then lifted the stay order on his activities in a March 18 verdict.

Three months later, Lofa County Attorney Cllr. Luther Sumo re-imposed the stay order following complaints from chiefs and elders of Gorlu. This term, Sumo sent in the police to enforce the stay.

“I have received several phone calls and complaints from the commissioner that the chiefs have threatened that if they cannot stop the pit-sawing and charcoal burning, they are going to protest and take unspecified actions, which we do not want,” Sumo said in a telephone interview.

“If I sit here and allow things to go off hand, who will be blamed at the end of the day… and we do not want chaos in our communities in Lofa.”

Despite Mr. Sumo’s order, Mr. Sulonteh continued to operate, sticking with the circuit court’s decision. Only the court could tell him to stop, not any individual.

His insistence fueled the townspeople’s anger. In July, Gorlu townsmen stopped him from transporting planks from the area, seizing a truckload of wood that was headed to Monrovia because he was defying the County Attorney’s stay mandate.

Mr. Sulonteh sued the townsmen for alleged “menacing, theft of property and disorderly conduct.” However, the Salayea Magisterial Court dismissed the case, citing a lack of evidence, court filings show.

After the September 11, Mr. Sulonteh halted his operations—for the time being.

“Presently, we are not doing anything in the forest,” he told The DayLight. “We are running after some documents for the same land in question to allow our lawyer to advise us on the next action to take.”

This story was a Community of Forest and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ) production.