A signboard at the Gheegbarn #1 Community Forest in Compound Number Two, Grand Bassa County, the setting for perhaps forestry’s largest scandal in the last decade. The DayLight/James Harding Giahyue

By James Harding Giahyue

BUCHANAN, Grand Bassa County – “The challenges in community forestry are self-explanatory. The companies will not perform. There will be some breaches by the community for tempering with the forest.”

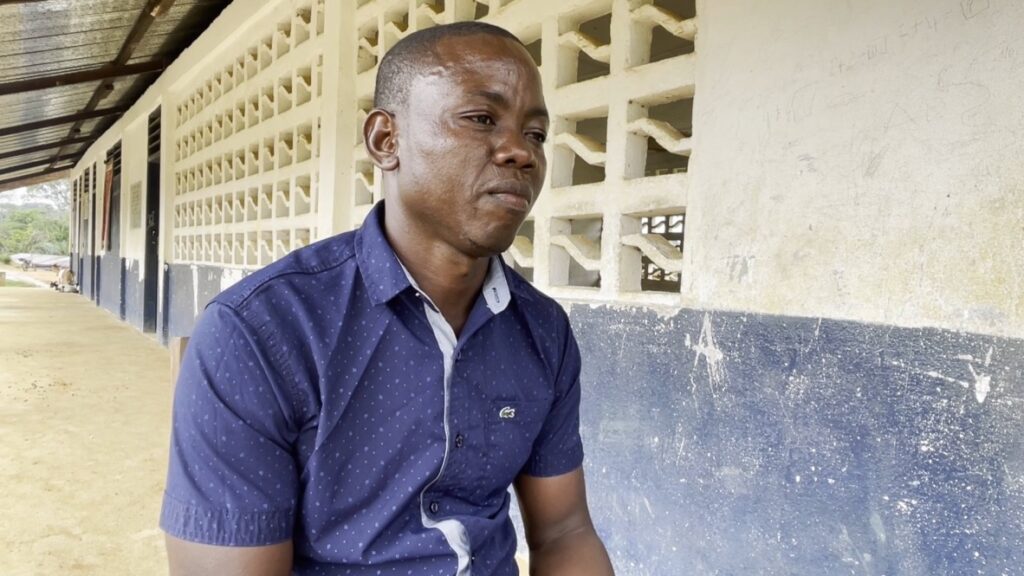

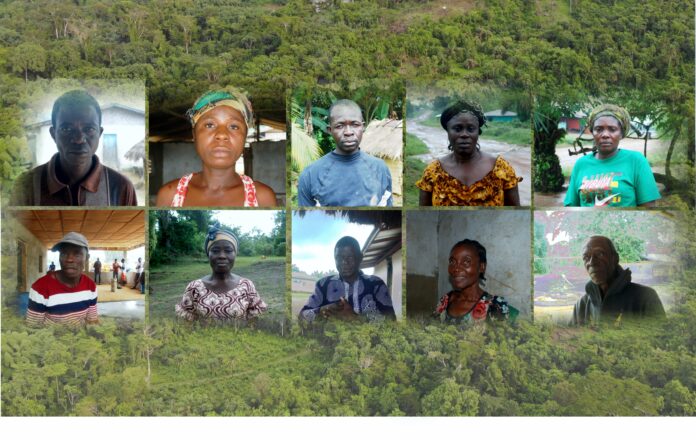

Jefferson Zoegbeh, the secretary general of Gheegbarn #2 Community Forest’s executive committee in Grand Bassa County, speaks at a recent meeting in Buchanan. Over 50 community land and forest leaders brainstormed conservation possibilities. Gathering from the west-central county and River Cess next door, they discussed ways rural people could benefit from their forests rather than logging.

It has been some 15 years since logging was reintroduced in community forests following the end of over a decade of Liberia’s bloody civil wars. Though postwar forestry guarantees communities’ benefits, locals have gained little from dozens of logging contracts countrywide, covering 2.3 million hectares.

Official records show that of the 186 logging companies that have existed since 2009, just four or five are active. According to a recent report, they owe communities affected by large-scale concessions US$21 million.

The meeting was the second of a series of community-based consultations, the the previous held in Ganta, Nimba County. The events’ organizers intend to incorporate communities’ views—and a report—into a proposal to the Liberian government early next year.

“The best way for communities to get their benefits is to reserve their forest,” says Piyigar Gaybeon, Zuzohn Community Forest’s chief officer in the same region as Gheegbarn #2. Zuzohn signed a contract with the Chinese-owned Booming Green, which was terminated by mutual consent. However, the company did not settle its debt to locals, including contractual projects before pulling out.

“If we can get anything from any company to reserve the forest, we will agree. We need the generation to come and meet the forest there.”

Organizers seek locals’ views on three ways they can benefit from conservation. The first is performance-based, where they get paid for a specific forest area that is easily measurable. The second is direct funding, which empowers communities without a third party and is less bureaucratic. And the third is enterprise development, where communities’ alternative livelihood programs are funded to keep locals away from the forests.

Silas Siakor, the country manager of Dutch NGO IDH and one of the organizers, explains that the idea is to enhance communities’ sense of forest ownership and management.

“By protecting their resources, they can access funds tied to conservation ownership,” said Siakor. “For example, payments linked to forest management should be transparently managed within community bank accounts, fostering a sense of collective responsibility and preventing misuse.

The idea is to balance conservation with community needs.”

Locals did not dwell on REDD+ or reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries, which activists have warned against. They also avoided carbon credits, trading and markets for which Liberia is still developing policies and legal frameworks.

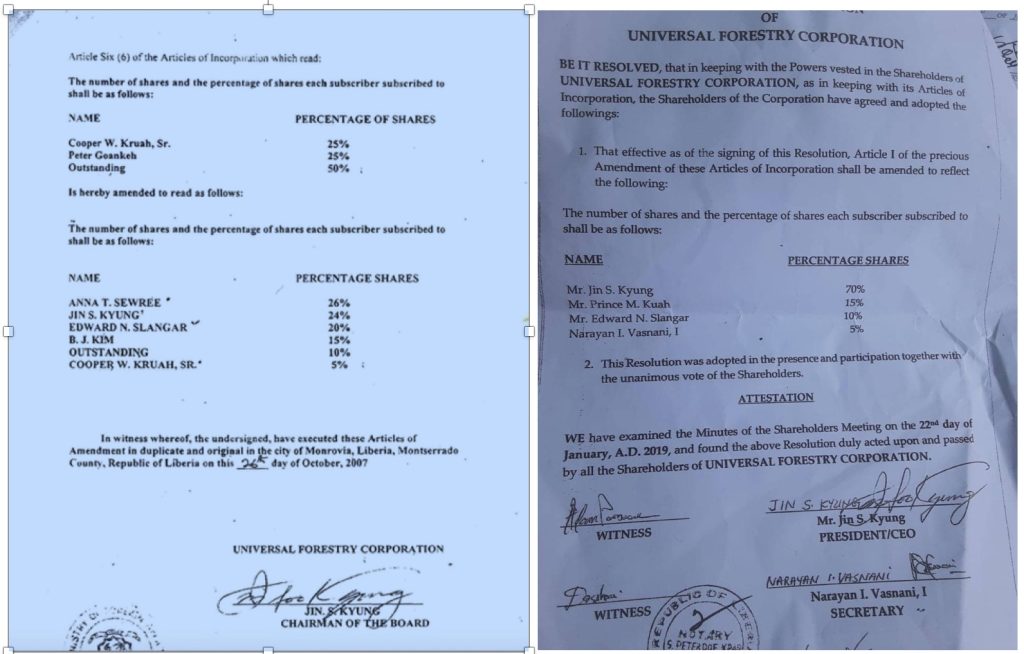

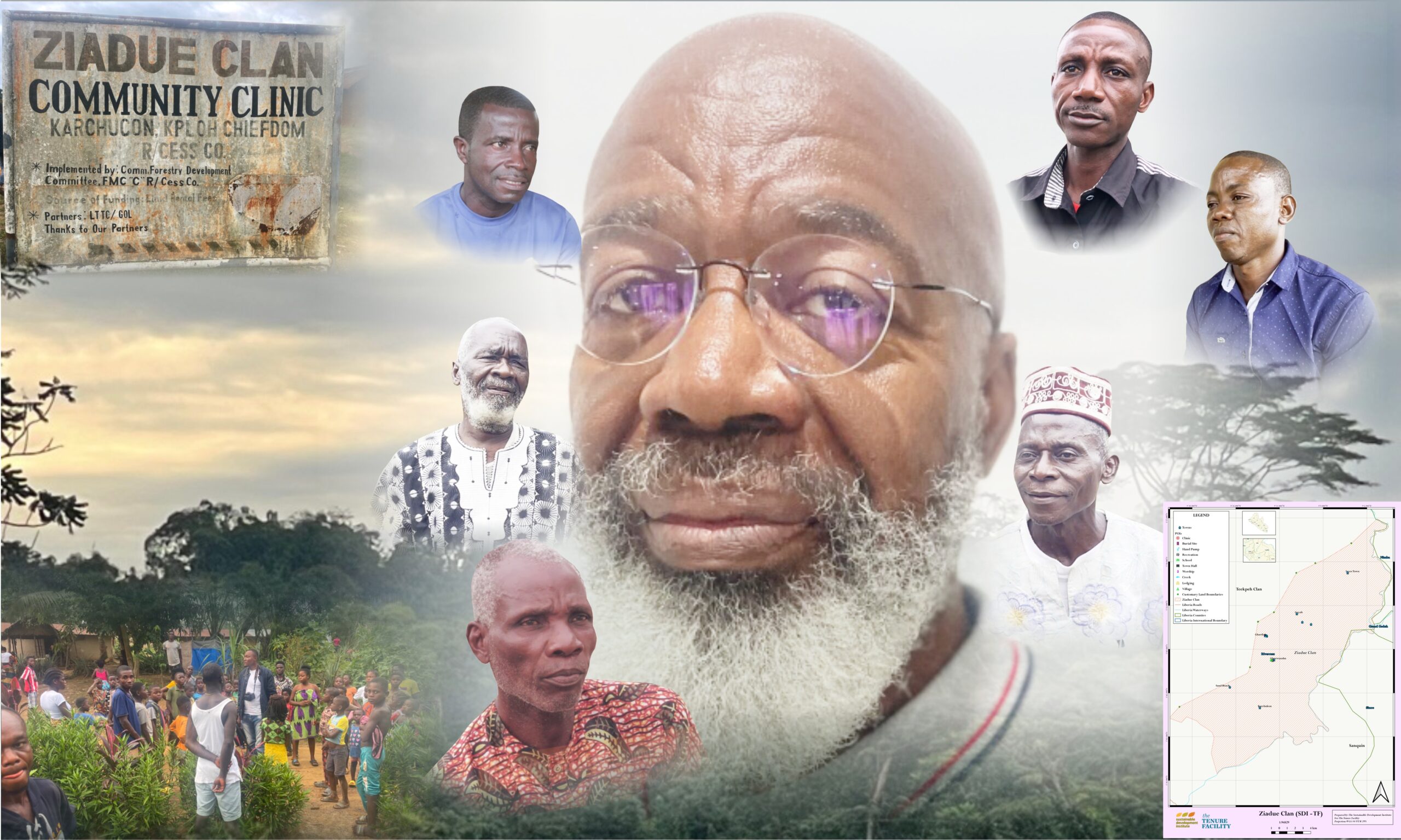

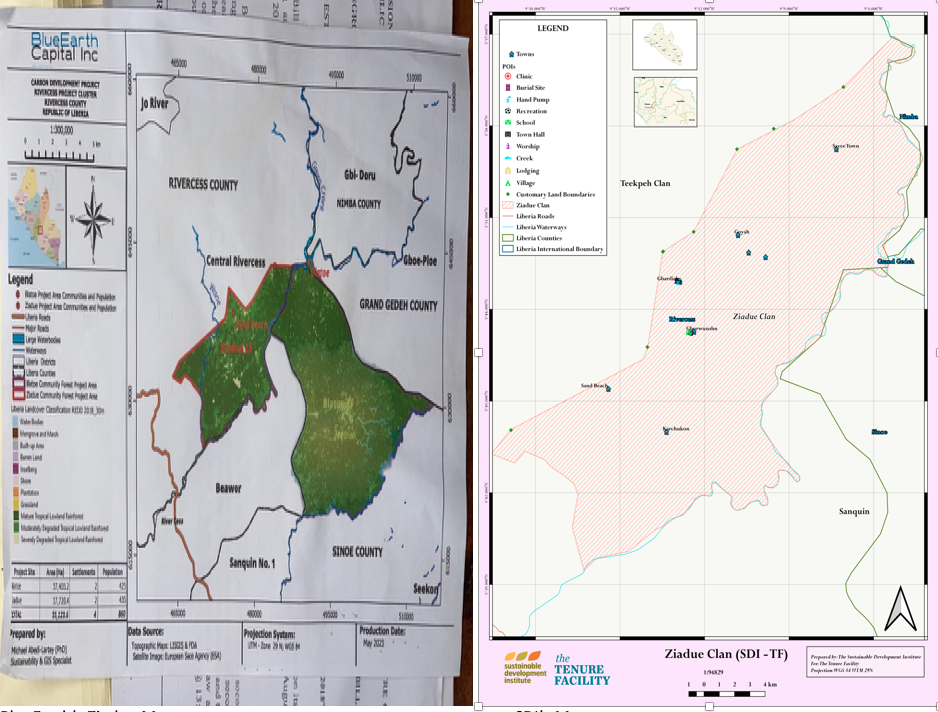

Ziadue, a landowning River Cess clan, has its own experience with carbon. Last year, the Environmental Protection Agency shut a deal between the clan and a company over alleged bribery.

But that glitch is nothing compared to the logging nightmares Ziadue and its neighbors—Teekpeh, Gbarsaw and Dorbor—have experienced. Ziadue seeks termination of a logging contract for a forest it shares with Teekpeh, while loggers fled Gbarsaw and Dorbor after illegally harvesting 550 logs in 2020. These experiences have inspired locals here to look to conservation.

“We the leaders of Ziadue, Teekpeh, Gbarsaw and Dorbor, have decided to get into conservation and are united. This way, we can get benefits and develop our communities,” says Emmanuel Marcus Roberts, CLDMC Chairman of Ziadue Clan’s community land development and management committee.

Caution

The community leaders at the event, including Kennedy Kaiuway of Gheegbarn #2, are convinced that his community should run one of the three workable conservation programs.

“That will be better for us than for one man to come to our forest, ship his US$10 million [worth of] logs, and we are left destitute,” says Kaiuway. A company called L&S Resources Inc. deserted the 12,000-hectare Gheegbarn #1, leaving behind debts, abandoned logs and unfulfilled projects.

Zoegbeh shares Kaiuway’s views but urges rural people to tread with caution. “This is a new approach. For us to know it, we have to investigate and do due diligence on it,” says Zoegbeh.

Like Zoegbeh, Paul Kahn Jr., the chief officer for Gheegbarn #1 Community Forest, has doubts in conversation and believes logging can still work.

Bordering Gheegbarn #2, Gheegbarn #1 has seen perhaps the worst forestry scandal in the last decade. A Ministry of Justice Investigation found that the FDA had awarded the West African Forest Development Incorporated (WAFDI) 14,000 hectares, exporting thousands of the illegal logs.

Amid the illegal activities, WAFDI did not pay locals their fair share of logging resources. Paul Kahn Jr., Gheegbarn #1’s chief officer, puts the debt at US$193,000 in project fees, US$3,125 in land rental and, an unspecified amount in harvesting. Kahn’s predecessors are accused of mismanaging US$200,000. There has been no work there since a community protest last December.

“I think it can change [a lot] of things in the communities,” says Kahn. He had been elected to his post last month after leading the protest.

“Train officials of the community forest. Raise more awareness in communities, making them understand how to manage their funds. The responsibilities of [members of the community forest leadership]. The responsibilities of the company.”