Top: This cartoon depicts Minister of Justice-designate Cooper Kruah in a conflict of interest when he served as Minister of Posts and Telecommunications. Then Minister Kruah retained his shares in the Universal Forestry Corporation, which ran a forestry contract and held several mining licenses between 2018 and 2023. Illustration by Leslie Lomeh for The DayLight.

By James Harding Giahyue

- MONROVIA – Minister of Justice-designate Cooper Kruah is a repeated forestry offender, with his company involved in illegal logging operations dating back to the Liberian Civil War era.

- Kruah’s Universal Forestry Corporation (UFC) was debarred from forestry in 2006, based on the United Nations Security Council’s recommendation

- UFC crept its way back into the sector—with assistance from forestry authorities—and continued its illegal activities

- UFC was involved in the infamous Private Use Permit Scandal in which it illegally received two permits at the detriment of local communities

- Later, UFC signed an agreement with a community forest in Nimba. Then the Minister of Posts and Telecommunications, Kruah remained one of its shareholders—a violation of the Code of Conduct for Public Officials and forestry’s legal instruments

- Kruah presented a fake document, which misspells his son’s name, to cover up his conflict of interest

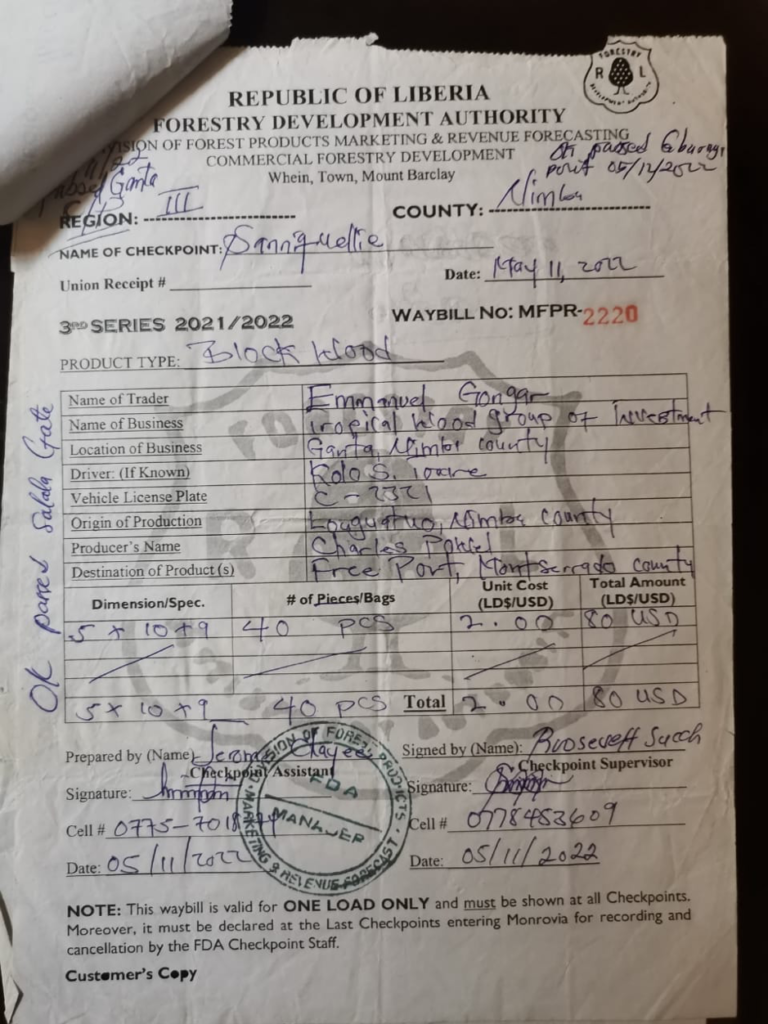

- UFC persisted with its offenses, abusing the rights of local people, conducting illegal harvesting and transport

MONROVIA – Cllr. Cooper Kruah, the Minister of Justice-designate, has a long history of being a forestry offender. His nomination contradicts the role of the Attorney General and undermines President Joseph Boakai’s expressed quest for accountability and the rule of law.

In his Inaugural Address, President Boakai promised to fight corruption and restore Liberia’s lost image in the comity of nations. Boakai restated that in his first State of the Nation Address.

Last month, Boakai appointed Kruah, a stalwart of the Movement for Democracy and Reconstruction whose support was instrumental in the Unity Party’s victory in last year’s elections.

Kruah is expected to appear before the Liberian Senate for confirmation. If confirmed, his job would be to prosecute individuals for alleged wrongdoings, sign concessions for Liberia and conduct oversight of several government offices.

But desk research, based on official records, United Nations reports and previous investigations by The DayLight reveals that Kruah may not be the right person for the post. It shows Kruah has broken forestry laws repeatedly with impunity, making no efforts to atone for his wrongdoings.

Kruah has refused to grant The DayLight an interview in each of the two times the newspaper contacted him. He preferred not to be recorded on the matter, which goes against The DayLight’s editorial policy.

Wartime logging

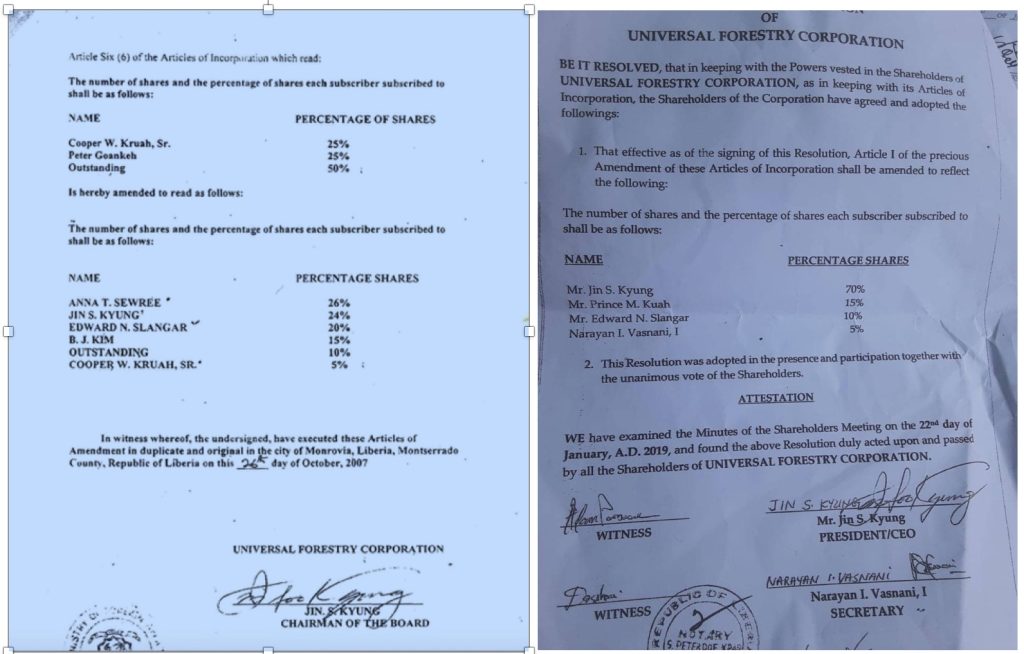

Kruah established Universal Forestry Corporation (UFC) in 1986, holding 25 percent of the company’s shares, according to its article of incorporation at the Liberia Business Registry. One Peter Goankeh held 25 percent while the remaining 50 was outstanding.

UFC was active in the early 1990s and early 2000s when Liberia became known for “conflict timber” or “logs of war.” Warring factions traded timber for weapons in two civil wars that killed an estimated 250,000 people.

The trade violated several United Nations arms embargoes on Liberia, leaving the Security Council to impose sanctions on Liberian timber. To lift the sanctions, the Liberian government at the time submitted itself to reform led by the UN and national and international civil society organizations.

Following a review of forestry concessions in 2005, the administration canceled all logging contracts, including UFC’s. The review found that UFC was not compliant with the industry’s laws and that its contract was not even ratified by the Legislature.

As part of the reform agenda, UFC and 69 other companies were expelled from doing logging business in Liberia. That move was further carved in the 2007 Regulation on Bidder Qualifications, which partially debars individuals associated with wartime companies from forestry activities.

An Illegal Return

In 2007, UFC amended its legal documents to add new shareholders. Kruah retained five percent shares in the company and the others were distributed among four other people, including former presidential advisor Edward Slangar and two non-Liberians: Jin S. Kyung and B.J. Kim.

In 2007 and 2008, UFC signed two illegal MoUs with Geetroh in Sinoe and Rock Cess in River Cess for logging rights, respectively, according to a 2018 Global Witness report. The communities had not gotten their community forestry status when the MoUs were signed. A 2009 law gives communities the right to enter into contracts with loggers upon the approval of the FDA.

Three years later, Kruah hustled his way back into the sector. The Forestry Development Authority (FDA) ignored UFC’s wartime activities and its qualification regulation. UFC acquired two private use permits and logging rights granted for private lands.

But a two-year investigation by Global Witness, the Sustainable Development Institute and Save My Future Foundation found UFC and other companies were illegally awarded the permits. It became known as the Private Use Permit (PUP) Scandal.

A government-backed inquest uncovered a lot of irregularities with UFC’s PUPs. It found that UFC did not follow any legal processes, did not obtain an environmental permit and that fraudulent persons had posed to be the landowners of its contract areas.

It also found that UFC made payments into a personal bank account, its Grand Bassa PUP area was larger than the actual land size and the one in Sinoe was issued for communal, not private land.

A UN Security Council report revealed that UFC’s Sinoe permit covered the same area as Atlantic Resources, another company.

For the second time in its history, UFC’s permits were canceled alongside 62 others. The Managing Director of the FDA Moses Wogbeh was dismissed and prosecuted for his involvement in the scandal. A moratorium on the issuance of PUPs remains in force to this day.

Conflict of Interest

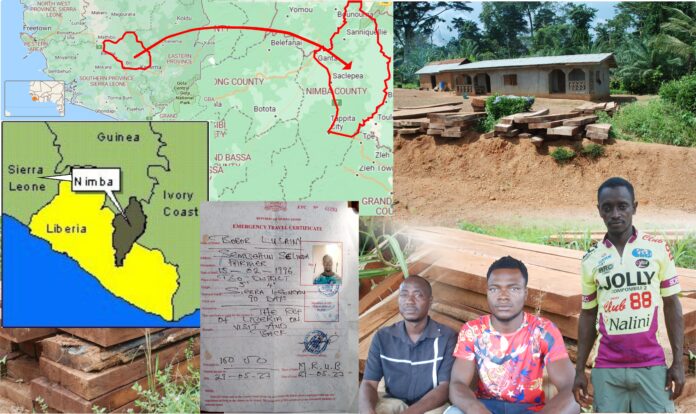

There is no public record of UFC’s activities after the PUP Scandal. However, UFC returned in 2020 with an agreement with the Sehzueplay Community Forest.

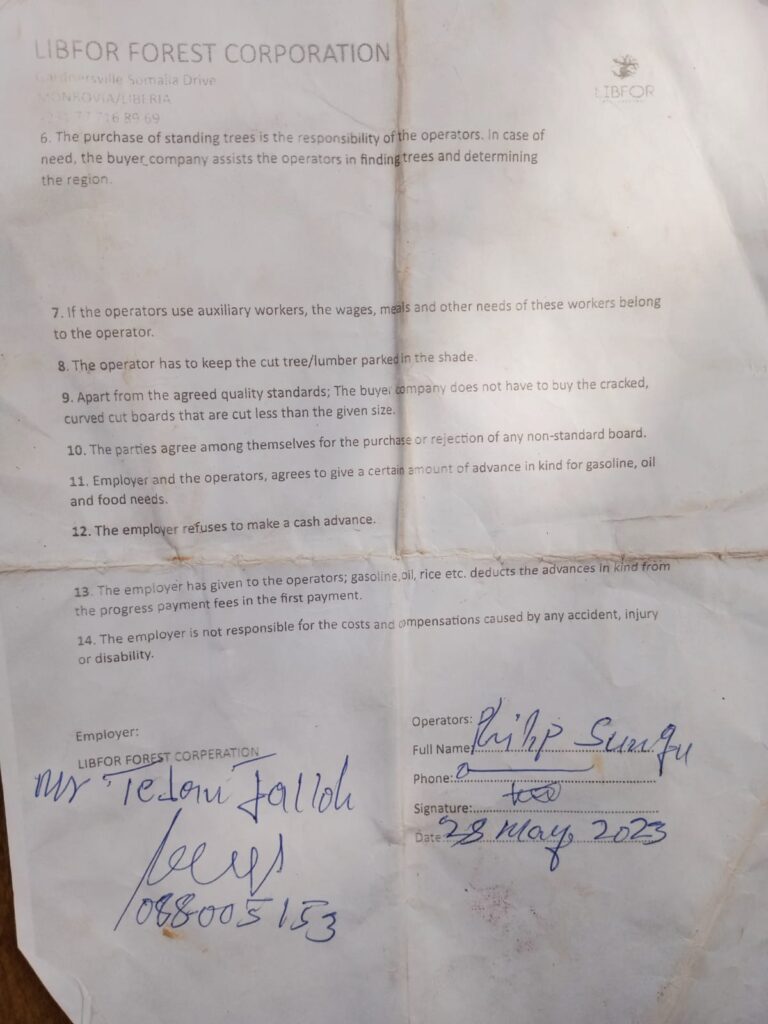

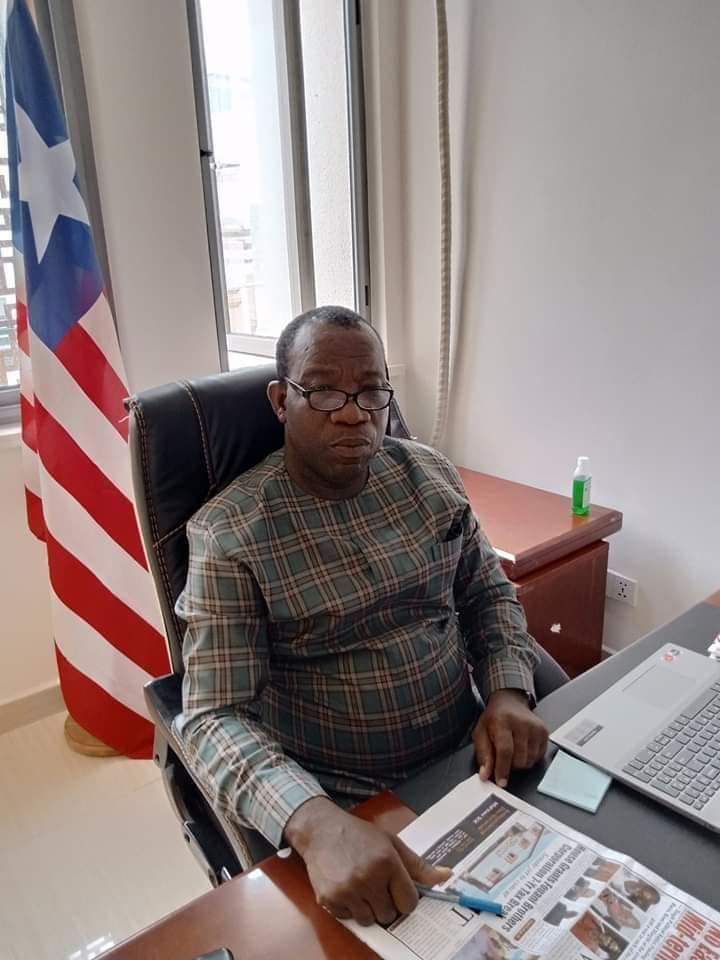

Kruah was the Minister of Posts and Telecommunications while serving as a shareholder and secretary of UFC’s board of directors when the agreement was signed.

That violated the National Forestry Reform Law of Liberia and the Code of Conduct for Public Officials. Both laws prohibit a government official from conducting logging activities. The violations were the subject of an investigative series by The DayLight in 2022.

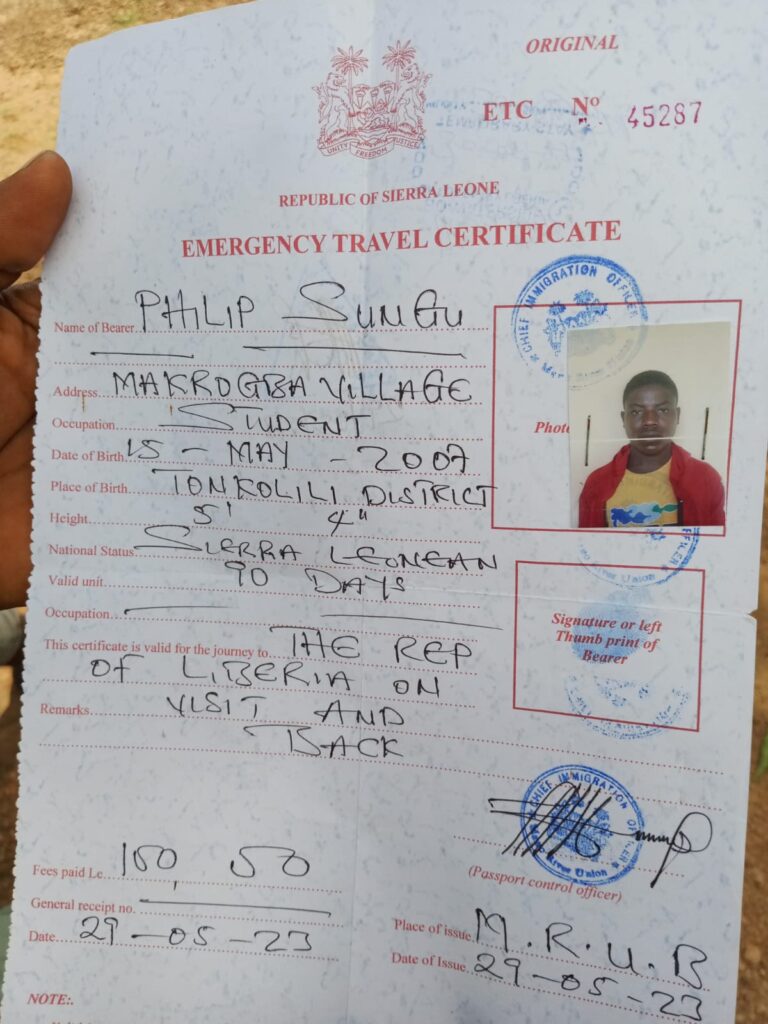

Kruah tried to cover up his conflict of interest but ended up committing more wrongdoings. A 2019 document he claimed to be UFC’s amended article of incorporation was not recorded at the business registry as required by law. Also, UFC’s tax history at the Liberia Revenue Authority (LRA) did not show it paid taxes for the amendment. UFC’s legal document at the business registry still carries Kruah and his five percent shares.

Moreover, the content of UFC’s so-called amended article cemented the evidence of the document’s fakeness. The document misspelled the name of Kruah’s son. Instead of “Prince M. Kruah,” it read “Prince M. Kuah.”

Then FDA Managing Director Mike Doryen promised to act but failed to do so. Penalties for forgery in forestry are a fine between US$10,000 and three times the funds Kruah received from UFC, or a prison term of up to 12 months.

But Kruah did not know, or he ignored the fact that he would not have resolved his conflict of interest by transferring his shares to his son. The forestry reform law mandates him to relinquish, or turn over his shares to a blind trust or a person outside of his control.

Illegal harvesting

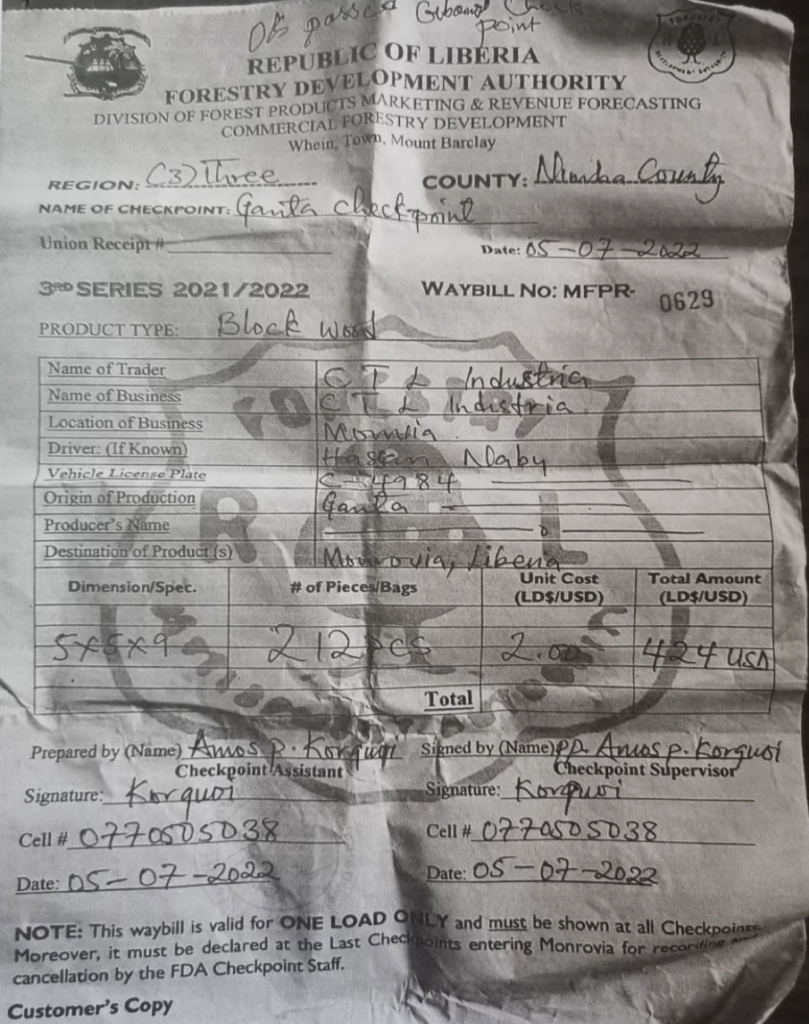

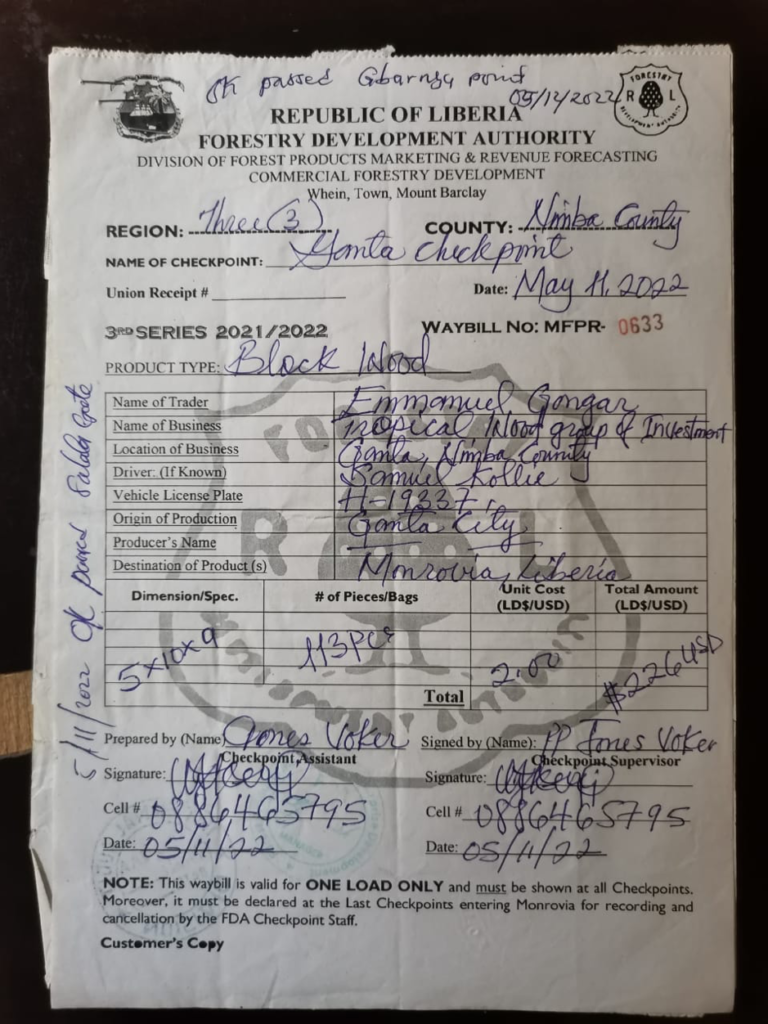

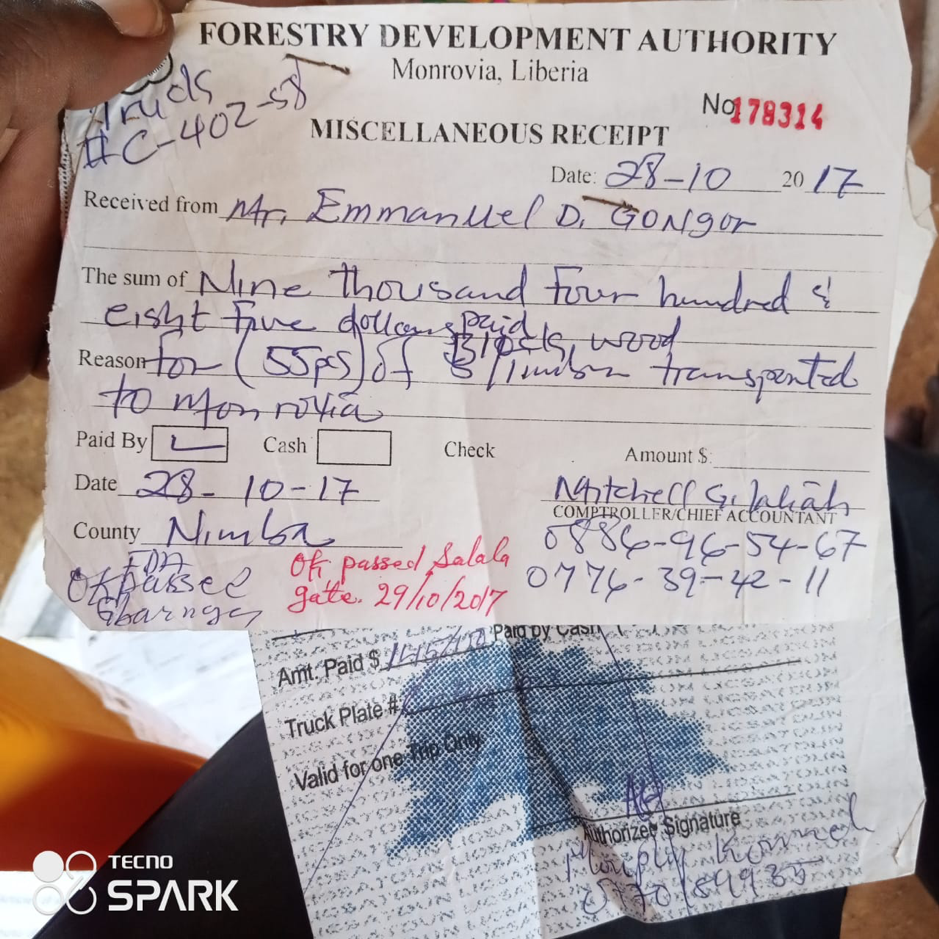

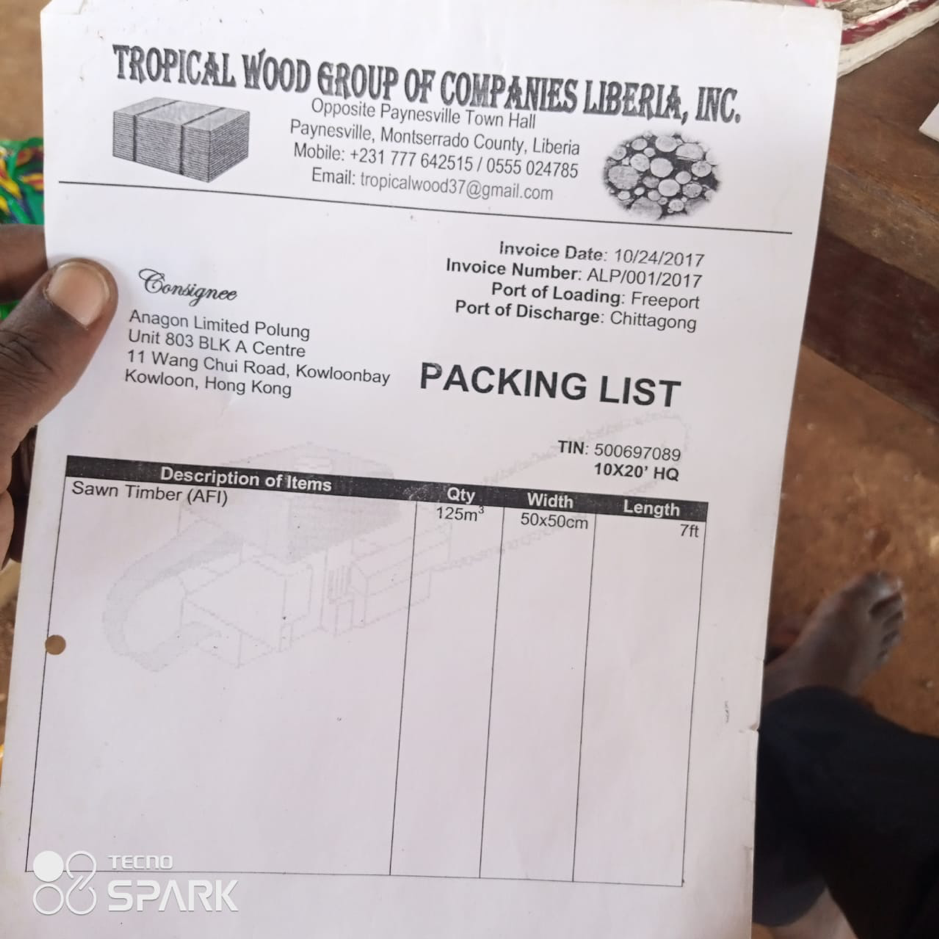

UFC carried out illegal logging and transport under his shareholdership. An August 2021 industry report found that UFC conducted “massive” illegal harvesting in and around the Sehzueplay Community Forest.

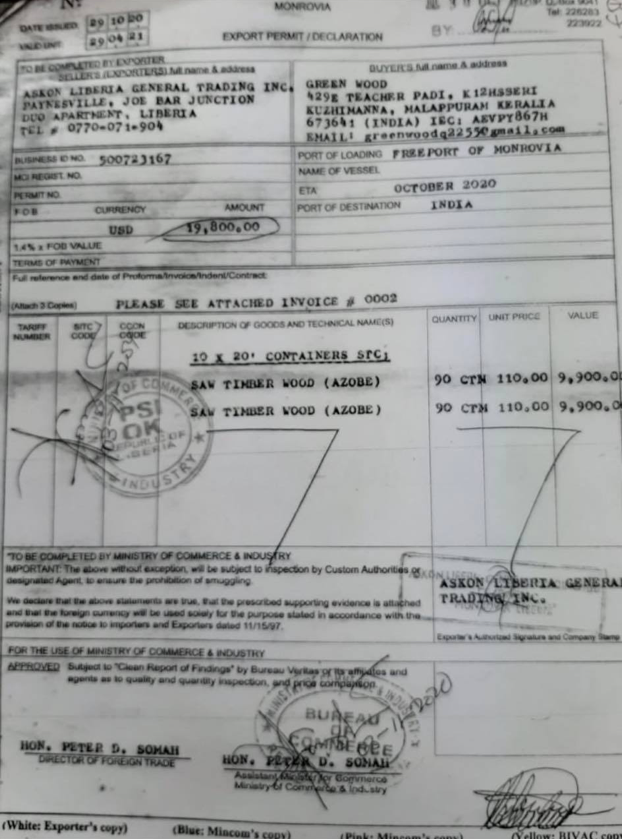

The report revealed that UFC was illegally transporting logs from Nimba to an illegitimate sawmill in Buchanan, Grand Bassa. Investigators suspected that UFC smuggled logs it had felled outside of Sehzueplay to the sawmill.

The DayLight had visited the forest and photographed some of the illegal logs mentioned in that report. It obtained a ranger’s memo to Kyung, UFC manager, informing him about the illegal felling.

“During our recent visit to your concession area, we discovered that you were doing illegal [felling]. You are fallen [trees] without being awarded a [harvesting] certificate,” the memo read, signed by Steve Kromah, the ranger responsible for forest contracts in the Tappita area.

The illegal harvesting was not UFC’s only offense. It unilaterally entered a subcontract with a logging firm. Sehzueplay or the FDA was not aware of the subcontract UFC signed with Ihsaan Logs Company (ILC), a forestry violation.

ILC is ineligible to conduct logging as Mohammed Paasewe, its co-owner, was still paying back funds he embezzled from the Liberian government when he served as Superintendent of Grand Cape Mount County.

The logs The DayLight photographed brandished, “UFC/ILC,” a reference to the unapproved subcontract.

Turns out, towns and villages that own the forest became the biggest victims. As of March 2022, UFC owed locals—and the government—US$155,000, the second-highest in the industry. It had yet to carry out a host of mandatory development projects there. That situation has not changed.