Top: Lower Bokan awaits the resolution of a border dispute between Sinoe and Grand Kru Counties to obtain its customary land deed. The DayLight/Derick Snyder

By Harry Browne

DIYANKPO, Sinoe County – An unsolved boundary issue between two towns in Sinoe and Grand Kru Counties is stalling a clan’s pursuit of a customary land deed.

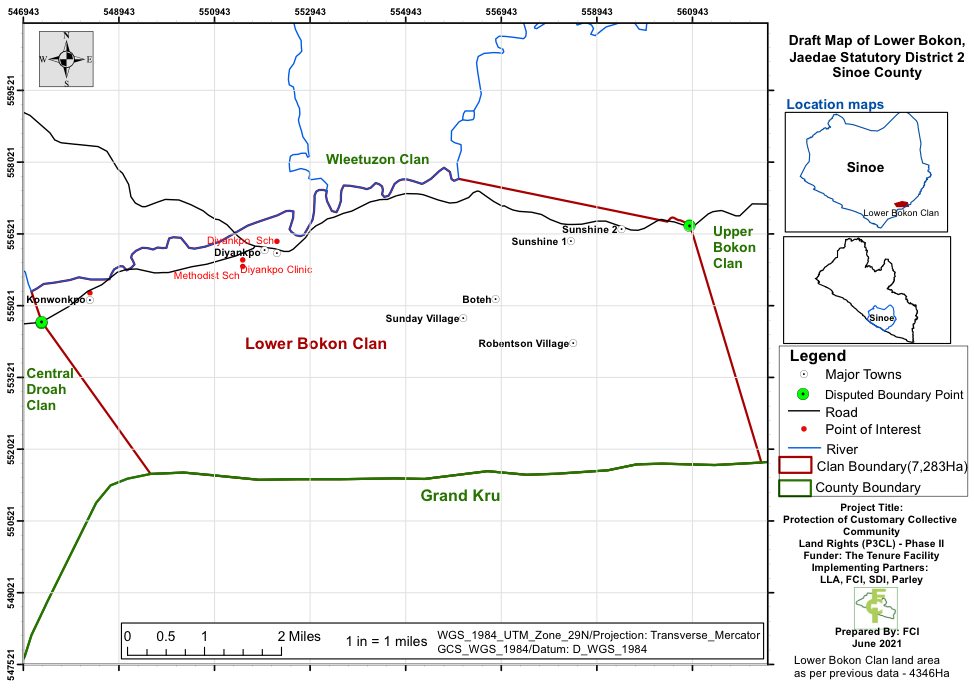

Diyankpo, a town in the Lower Bokon Clan in Jaedae District, Sinoe County, has a boundary dispute with Neeklakpo in Grand Kru County. Lower Bokon is pursuing a customary land deed but has seen its efforts stall due to the disputed area, approximately 8,000 hectares.

“We could not proceed with the survey. We had to put a halt to it, come to town, and see how we can resolve the conflict before going back in the field,” says Dr. Mahmoud Solomon, the Acting Commissioner of the Land Authority’s Department of Land Administration. Solomon says Diyankpo and Neeklakpo recognized two different boundaries that must be harmonized.

“Diyankpo one of the towns in Sinoe County is showing points that belong to their land that falls in Grand Kru. Neeklakpo is showing points in Sinoe County that belong to Grand Kru,” Solomon adds.

Solomon discloses that the Land Authority engaged the Liberia Institute for Geo-Information Services (LIGIS), the National Election Commission and the National Legislature—all of whom have county border data—to resolve the dispute.

“The Acts that created those counties will be able to show the boundary. Even though it will not be clearly defined it will give us an idea of the commencement and all those towns that fall within a particular clan,” Solomon explains. He says the matter would be resolved soon.

‘It was so difficult’

Lower Bokon borders the Beah Clan along the Dugbe River. Beah Clan had recognized another boundary apart from the one both clans had recognized for generations. However, the Beah Clan later dropped its contention, ending the conflict.

Lower Bokon had another situation with Neejlah Clan resolved in an MoU last December. Both parties now agree a local hill is their boundary. They have decided to use the boundary for future surveys, and that residents who violate the MoU be called out.

“It was so difficult in [resolving the boundary issues]. Other communities would say this is the boundary and other communities would disagree,” recalls David Sonpon, the chairman of the Lower Bokon Community Land and Development Committee.

“Some people, whenever you reach a boundary harmonization stage, they want to claim another side. That is the problem,” adds Matthew Weseh, a mobilizer with the Foundation for Community Initiatives (FCI).

FCI has worked with Lower Bokon since 2019. The NGO’s work with the clan is part of a US$3.45 million project funded by the International Land and Forest Tenure Facility. The Margibi-based NGO also works in the same district as Gboyonnoh Karmbo, which awaits the Land Authority to survey the clan’s land area to get a deed.

‘There must be an agreement’

Home to over 5,000 people in the Jaedae District, Lower Bokon identified itself as a landowning community in 2019. In these five years, it has established a governance body, the Community Land Development and Management Committee (CLDMC). It has bylaws and a constitution, and mapped its 7,283-hectares land, according to FCI.

The clan has a rich culture. Kru is the dominant language. There is a traditional council that is headed by a chair. The highest traditional person is the High Priest, who conducts the Poro Society or the school for men. The leader of the clan is the Clan Chief, while the heads of towns are the Town Chiefs. Beans cannot be planted on the clan’s land, and no one builds a house or hut there with thatches.

Road connectivity is a problem for the 13-town Lower Bokon Clan. Some of the communities—such as Sunshine, Diyankpo, Sunday Village, and Konwonkpo—are accessible by vehicle while Neponklee is by bike only. The roads to the rest of the communities are by walking.

Once the boundary dispute with Neeklakpo is resolved, Lower Clan will be ready to get its customary land deed. It has forests and a huge potential for gold. The Land Rights Act of 2018 empowers communities to own lands where their ancestors lived.

Residents of Lower Bokon welcome an opportunity to manage and benefit from their land, a right they have even without a deed.

“Before you can get into our forest, there must be an agreement,” says Theresa Wleh, the chairlady of Diyankpo and widow of four children. “When there is no agreement, we will not allow you to get into our forest.”